Letters from the Border

Two retired soldiers, once divided by a border, find connection through handwritten letters—and discover that peace begins with listening.

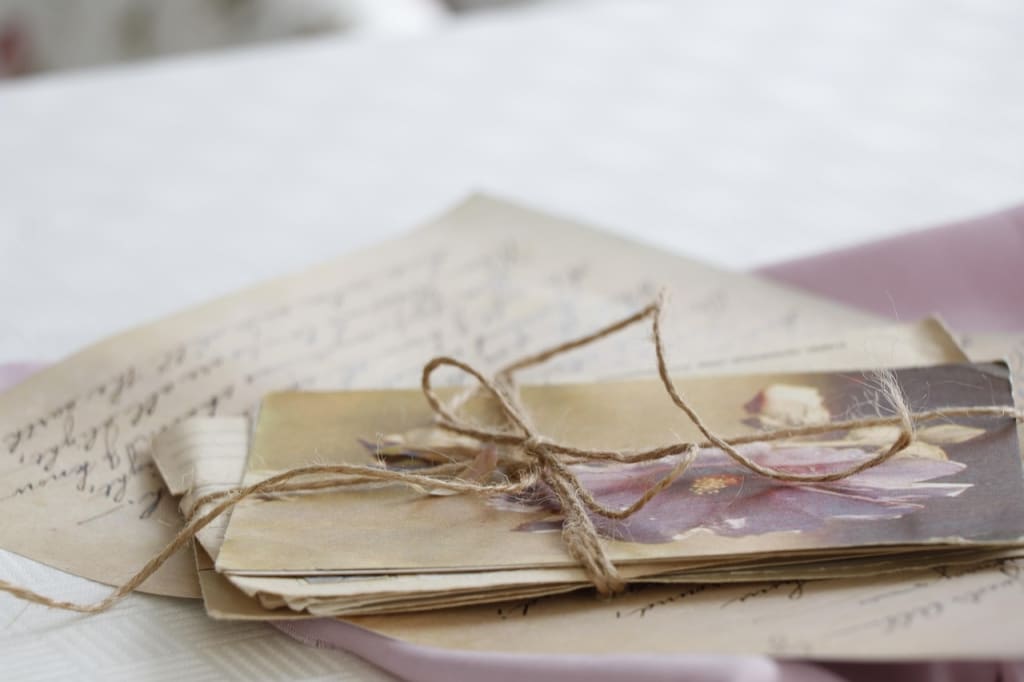

The first letter came on an unusually quiet morning in October. Colonel (Retd.) Arvind Mehta, sipping his cardamom tea in the courtyard of his home in Amritsar, turned the envelope over with curiosity. The handwriting was neat, the paper scented faintly with something floral—unexpectedly gentle for a letter that had come from across the border.

"Dear Colonel Mehta," it began, "I hope this letter reaches you in good health. My name is Brigadier (Retd.) Salim Khan. We never met in the field, but I know of you. I served across the fence during the same years you did. Now that the border is quiet and we are men of peace, I thought perhaps we could speak—as veterans, as old soldiers who no longer fight, and perhaps as friends."

Arvind chuckled, folding the letter carefully. His wife raised an eyebrow.

"Who writes letters these days?" she asked.

"An old Pakistani soldier," Arvind replied. "Says he wants to be friends."

The idea was strange—and yet, comforting. For decades, Arvind’s life had orbited around the border. It had been his assignment, his obsession, and later, his burden. But things had changed. The last skirmish had been years ago. Both countries had signed the Peace Corridor Accords, allowing free passage of civilians and goods in specific zones. No shots, no standoffs—only watchful quiet.

He wrote back.

Over the months, the letters grew longer.

Salim shared stories of his childhood in Lahore: cricket in the alleys, kites over the rooftops, and the first time he saw snowfall in Murree. Arvind responded with tales from Shimla: monsoon rains, army drills in the mud, and the way the hills turned golden in November.

They never discussed politics.

They wrote of their families, their scars, the odd dreams that still visited them in the early hours of morning—always the same dreams of patrol routes and radio static, of voices that no longer answered.

Arvind learned that Salim’s wife had passed away a few years before. Salim learned that Arvind had a grandson who liked astronomy.

“I envy that,” Salim wrote. “A child who looks at stars, not borders.”

In one letter, Salim enclosed a photo: two young officers, smiling in black-and-white, one in olive green, the other in khaki. He’d found it in an old trunk. It was from a peacekeeping exchange drill in 1983, briefly forgotten in the tide of history. There, standing beside Salim, was a much younger Arvind, holding a cricket bat.

Arvind stared at the photo for a long time. He didn’t remember the moment clearly, but the familiarity was undeniable.

“So we did meet,” he wrote back. “Before the uniforms hardened and the maps mattered so much.”

Eventually, their story made its way into a veterans' magazine. A journalist picked it up, and suddenly, they became symbols—not of war, but of what follows after. Invitations came: to speak at summits, to sit on panels, to share their story of letters that crossed no-man’s land.

They declined most of them. Fame was never the point.

Instead, on the 15th of August, they agreed to meet—not in India or Pakistan, but at the Wagah Peace Pavilion, the one place where both flags flew side by side, unlowered.

They hugged like old brothers.

Tourists clapped. Cameras flashed.

But neither noticed.

Back home, Arvind kept the letters in a wooden box. Some were stained with tea, others creased at the edges. He had Salim’s handwriting memorized now—steady, deliberate, a little slanted to the left.

In the last letter he received, Salim wrote:

“I used to think peace was silence. Now I know it’s the sound of someone replying.”

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.