There were exactly four thousand, nine hundred and thirty-one kilometres between Paraburdoo and Franklin, and Jarli reckoned she had cried at least a hundred tears for every single one of them. Though not as many as she’d cried since she’d lost her adored Dad suddenly to a heart attack nearly six months before. That’s why they were in Franklin; her Mum had family here in Tasmania, and Mum said this is where she needed to be. Somewhere deep within her, Jarli understood that. She had been scared to see the way her Mum had changed since Dad died. Since it was just the two of them now, Jarli sometimes felt the weight of responsibility for making sure Mum was all right. It might be a relief to share that responsibility with someone else. But leaving Paraburdoo! It was her birthplace; it was her Dad’s country; it was everybody and everything she knew.

Jarli’s Dad was a Yinhawangka man on his father’s side, and Jiwarli on his mother’s. Yinhawangka was the Aboriginal country on which the town of Paraburdoo now sat, in what we know as Western Australia. Jiwarli was a neighbouring group. Since around 1860, Jarli’s ancestors had been shunted around the state, having been removed from their countries by whitefellas. Many of them died, either with the new diseases the invaders brought, or from broken spirits. Her Dad was one of the few she knew of who’d returned to his ancestral country to live, and Jarli felt a disturbing sense of betrayal by leaving. At the age of eleven, however, she had no choice in the matter, and so at the end of the year, they had packed up the house, said gut-wrenching goodbyes to their friends, and begun the long, long journey to Tasmania.

It was her Mum’s younger brother, Thomas, who had offered them sanctuary in his quirky cottage in Franklin, a small hamlet about an hour south of Tasmania’s capital, Hobart. Thomas was still single, and worked as a photographer and freelance journalist. As a journalist, he wrote on a wide range of issues; as a photographer, he specialised in wildlife, and in particular, birds. In her memory, Jarli had only met him once, about two years before when he’d visited them in Paraburdoo. She’d liked him; his cheeky, smiling eyes in his suntanned face beneath a messiness of blonde hair. Jarli knew that Mum had a special affection for her little brother, and she was relieved to feel her own anxiety and the burden of responsibility lift. She felt comforted by this new sensation of being among family that extended beyond her parents.

Paraburdoo and Franklin were approximately the same size in terms of population. There the similarity ended. Paraburdoo was a mining town, established only in the 1970s, and situated on the fringes of a desert. Franklin, tumbling down gentle hills to the bank of the Huon River, had been established and named for a remarkable woman before whitefellas had even set eyes on Yinhawangka country. Paraburdoo, sitting above the Tropic of Capricorn, was hot, averaging 40 degrees Celsius (105 degrees in the old money) in summer, and not much less in winter. The town was flat, although some mountains, including one called Mount Nameless, could be seen from there. Franklin, on the other hand, felt to Jarli as if it must be closer to the Antarctic Circle. She’d been taken aback to see snow on the distant mountains when they’d arrived at the beginning of summer, and disgruntled that she needed blankets on her bed at night.

Contrasts of landform and climate aside, Jarli had not been able to resist a fascination with the animals and birds that lived here. Thomas was the ideal guide to the unique fauna, much of which was now extinct on mainland Australia, thanks to introduced European predators such as the fox. Fortunately, the moat around Tasmania had so far protected it from this particular villain. During the day, Thomas had introduced Jarli to the adorable marsupial pademelons, and the hilarious native hens, known by locals as ‘turbo chooks’ because of their legendary running speed.

At night, they had squatted silently and patiently in bushy hideaways, Thomas with camera in hand. They had been rewarded with sightings of spotted and eastern quolls, bandicoots and the ferocious little Tasmanian devil.

It was on one of these nocturnal excursions as they were rising from their hiding place, that they sensed movement above them. Looking up, Jarli was startled by a ghostly form gliding quite closely above them, and then into the bushland.

“Blow me down!” breathed Thomas incredulously, “That’s a barn owl!”

“Haven’t you seen one before?”

“Not in Tassie, no! We have masked owls, which are kind of cousins, but not these!”

“Where has it come from, then?”

“I’ve no idea; I mean, they have been known to come here from the mainland. They can fly over a thousand kilometres, but it’s very rare. I’ve never seen one here before.”

“Why would it fly all that way?”

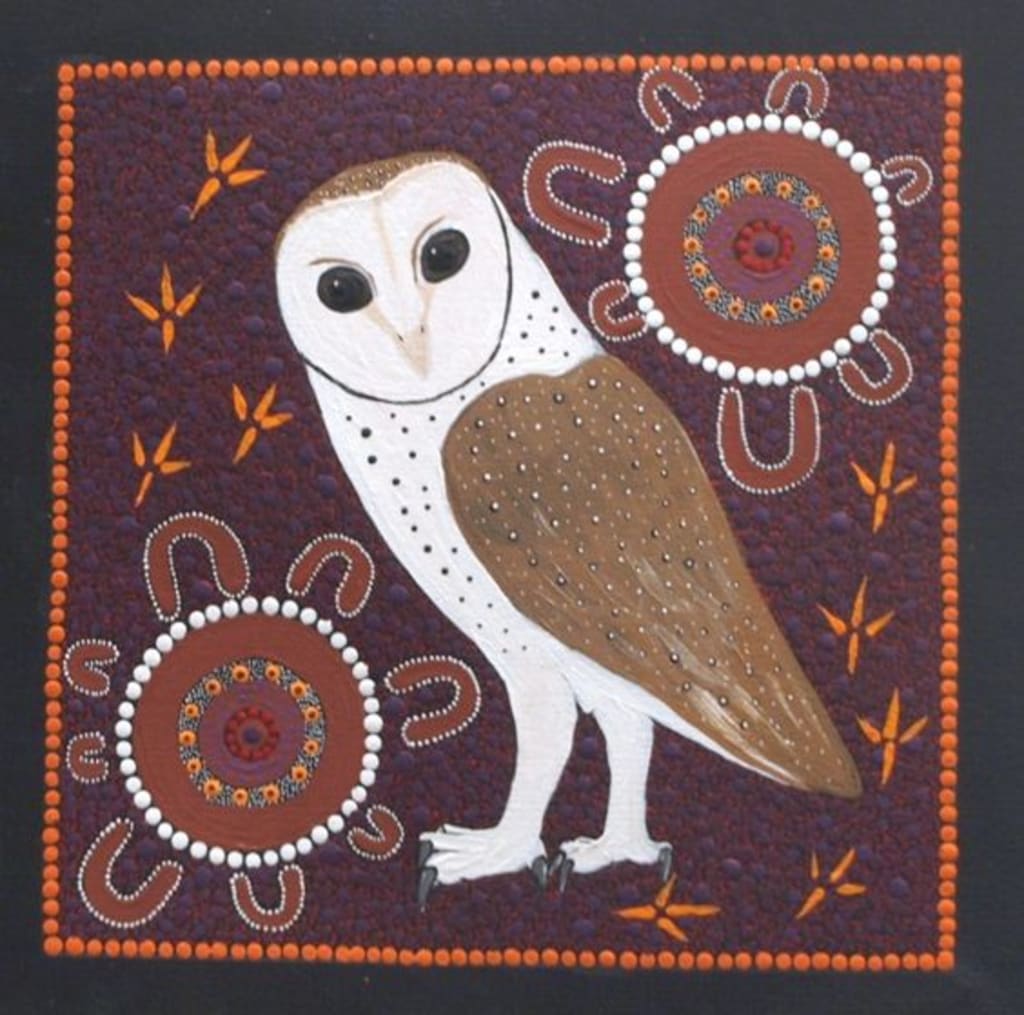

“Search me. Hey - maybe it’s come to see you! You’re its namesake, aren’t you?”

Jarli’s Dad had named her, with Mum’s blessing. ‘Jarli’ was the Jiwarli word for the white owl, or the barn owl as it was later known. Although the white owl was associated with death in many Aboriginal groups, it was also thought to be a messenger and a guardian; a protector; a light in the darkness. The death meaning was not always taken literally; sometimes it was about the death of one part of life, and the beginning of a new one. Jarli was proud to carry a name from her grandmother's country, and grateful that her father had bestowed it upon her.

As was her custom now, Jarli summoned memories of her Dad after she'd climbed the steep stairs to her little loft room and got into bed. She saw his beautiful face: the unruly curls, the mischievous dark eyes, and the dimples that she now wore in her own cheeks. His hands, the size of dinner plates, pointing out the constellations in the clear skies above Paraburdoo, or playing his guitar. His voice, as he told her the old stories about those constellations. “Night-night, little owl. Snuggle down in your hollow tree nest” was his lullaby for her each night. He often called her ‘little owl’. Now no-one did. The tears that had trickled across her face and into her ears began to dry as she drifted off.

She dreamt of the white owl. It was a full moon night, and she was following the owl through a forest. It would glide for a while, then perch on a branch, turning its head and its heart-framed face to watch and wait for her to catch up. Other animals were there, too: pademelons, possums, quolls, bandicoots and devils, all going about their night-time business, but pausing to call out welcomes to her as she passed. The edge of the forest opened to a beach, the froth of the small waves lit by the moon, which was now in full view. Jarli danced and cartwheeled along the hard sand at the edge of the water, laughing and calling to the owl as she went. It called back to her as it wheeled back and forth, back and forth above her…

The new life in Franklin went on: Mum got a job counselling youth in the Huon Valley, joined the local Landcare group, and became addicted to antique auctions. She began to resemble the person that Jarli had known and missed. Thomas received huge kudos and gained minor celebrity status in Tasmanian wildlife circles, due to the rare images he’d been able to capture of the barn owl, subsequent to their first sighting. Amidst his new-found fame, he also fell in love.

Jarli went to the local school, which was even smaller than Paraburdoo in terms of student numbers. Having come from a school in which Yamaji kids comprised a quarter of the population, Jarli was initially gobsmacked to find that not a single person in Franklin appeared to be Indigenous. Over time, she discovered that there were, in fact, descendants here of those who had survived the horror of what had been perpetrated in Tasmania. She made new friends, and kept the old ones up to speed. She developed new skills and interests, including sailing (something that was unthinkable in her former life), and she had become a part of a fiddle group, under the tutelage of a lovely local couple. This latter interest had provoked a surprisingly emotional response from her Mum, who had explained it was about her Irish heritage.

Despite her early misgivings, it was undeniable that there was much about this new life that Jarli liked. She still felt the pull of her Dad’s and Grandmother’s countries - her countries - and occasionally, she questioned whether it was right for her to be here. She wondered if her Dad could somehow see her; where she was; what he thought about it. Strangely, she felt that the presence of the owl had played a part in soothing these anxieties. Evidently, it had nested somewhere nearby, and she had seen it numerous times, either from the hides with Thomas, or from her loft window at night. It gave her a feeling of connection between her old life and the new; the here and there; and melded them into a harmonious whole.

Jarli’s Dad was older than her Mum by about ten years. At fifty-seven, he was hardly elderly by non-Indigenous standards, but it was not an unusual age for Aboriginal men to succumb to heart disease, or one of the other illnesses which had arrived with the tall ships. Anticipating that he would be first to depart, he had told them both of his wishes: he wanted to be cremated, and for his ashes to be spread on his traditional land; at least, some of them. He’d also said, dimples deepening: “Take me somewhere wild! Somewhere deadly!” (‘deadly’ being an Aboriginal expression for ‘amazing’). They had honoured his wishes, spreading some of his ashes at a stunning waterfall in the National Park bordering Paraburdoo. The rest they had brought with them, unsure of what might qualify as ‘deadly’ in this new land.

An answer came one afternoon when an enthusiastic Thomas informed them that he had it on good authority there would be an aurora later in the evening. Tasmania was one of the best places in the world to view the Aurora Australis, and southern Tasmania was better still. So it was that on a small, nearby beach the three of them sat under salmon-coloured skies, waiting for the cosmos to perform.

As the darkness approached, an undulating river of light began to flow across the horizon like the overture to a symphony. The first movement began in arresting style, with astonishing shafts of light tinged with greens, pinks and purples erupting from the river and shooting high into the sky. It was only later, when looking at the footage Thomas had taken, that they discovered the truly spectacular nature of these colours; colours that their human eyes were incapable of seeing. The light shafts then proceed to dance like spirit beings across the horizon, and Jarli recalled her Dad’s stories of the Min Min lights. These, however, were not individual points of light; the whole sky was taken up with this joyful, cosmic ballet. Jarli could scarcely believe it.

Mum held the urn against her body as the two of them stepped into the shallows of the water. They knew that this time and place could not be rivalled for ‘deadliness’. Jarli, having glimpsed the awesome power of the universe, knew that her Dad saw her, and rejoiced that she was here. As Mum removed the lid, they felt the silent wings above them.

*****

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.