Compensation

When your deceased husband looks like a celebrity

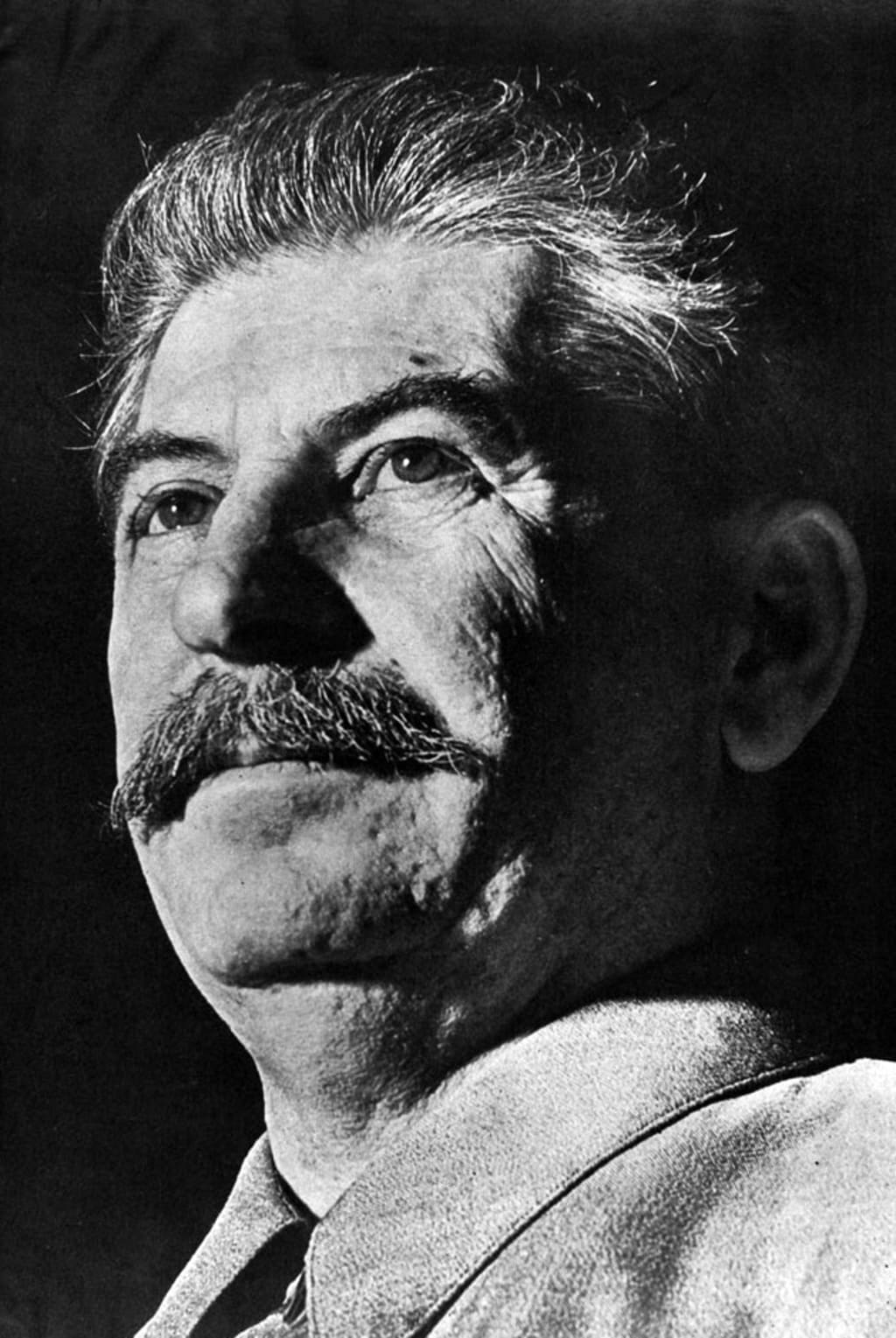

When Mr Starlin died, his widow decided to right the wrong of their 30 years of marriage. Rather than work, the old man preferred to read. From the time that he got out of bed until he put the light out before sleeping, his nose was in a book. He wore a huge moustache, which is wife trimmed. His eyes were permanently narrowed due to the continuous reading. He even had the same laugh lines as an infamous character who strutted the global stage several decades before. Meanwhile, Mrs Starlin took in clothes for alteration and went out charring three days a week. She grew vegetables in the back and front gardens of their terraced house in a cul-de-sac off the main road. The only time Mr Starlin rose from his armchair was to tap on the window and demand when lunch or tea was ready.

After the first five years of nagging her husband to get a job, she was heartily fed up. Many a time did she consider leaving him for Mr Kendall the plumber, who lived across the street. Mrs Starlin had a shrewd idea that Mr Kendall fancied her because he had bought her a drink or two in the Queen’s Head, which is more than her husband ever did, preferring to buy books on Marxism, the selected writings of Lenin and Trotzky, and the scribbling of another prominent figure in early 20th century Russian history.

After ten years of childless marital misery, Mrs Starlin gave up, hoping that her husband’s unhealthy lifestyle that consisted solely of eating, reading and sleeping, would end in a heart attack or stroke. But the old man insisted that he would be remembered for a new revolutionary theory, based on Marxism and Leninism, hence the reading. Yet me made no notes or produced any tracts or articles. Besides, who would read them? Mr Kendal said that society was going down the tubes.

‘That’s not a political observation, Mrs S,’ he laughed. ‘I see it all the time in my business.’ He drank up and left, never to be seen again as a few days later, he was crushed under a load of pipes for a water main. The coroner gave an open verdict. Hopes of a more fulfilling life with Mr Kendall dashed, Mrs Starlin continued clothes alteration, charring and market gardening to pay the utilities and council tax. The house she had inherited from her parents before she married Mr Starlin, but the woman aged before her time, not so much careworn, more with boredom.

Two decades later, the moment she had been waiting for came. One moment, Mr Starlin was sitting in the threadbare armchair, re-reading volume two of Kapital. The next moment, the volume had fallen from his lap and he slumped forward with a breath that made Mrs Starlin understand the expression ‘expired’.

She left him for an hour. She checked his pulse. There was none. Under his nose, she held a small rectangular mirror. It did not mist up. She did not call the local newspaper to have his expiry mentioned in the births, marriages and deaths. However, she did call her doctor, who, with little fuss, issued a death certificate. She presented herself to the borough registry the following day. On the way back, she called in the chemist on the main road near her house.

The shop door opened with an impatient ‘ding’.

‘Be with you in a moment!’ the chemist called out from the shadow behind the dispensary. Mrs Starlin waited patiently. She had made a mental list of what she was going to buy.

Mr Lambert was whispering to the teenage shop assistant. Mrs Starlin could pick out the words ‘condom’ and ‘protectives’.

‘Now then, Mrs S. What can I do you for?’ he chirruped, grinning.

‘Good morning. Formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde and perhaps some phenol, please.’

‘Doing a spot of embalming, are we, Mrs S?’

‘Yes.’

‘Favourite pet?’

‘You could say that.’

Mrs S boldly left the shop and disappeared into her house.

A few days later she was on the platform for the London Waterloo train. She saw Mrs Lunn, who lived a couple of doors up the street.

‘Hello, stranger,’ Mrs Lunn called out from the end of the platform.

They exchanged pleasantries. Mrs Starlin explained she was going up to London for the day. Mrs Lunn was not. She was going to change at Havant for Petrograd and on to Gori. Mrs Starlin’s eyes lit up.

‘Do you mean —?’

‘The very place,’ Mrs Lunn said, whereupon Mrs Starlin asked if Mrs Lunn could buy a few items for her. Mrs Lunn fumbled around in her handbag, pulled out a pen and a diary for 1969, and hastily scribbled her neighbour’s wants. When she alighted at Havant, Mrs Lunn said, ‘Nakhvamdis.’

‘Pardon?’

‘That’s what he would have said, you know. Russian wasn’t his first language.’

‘If you say so, Mrs Lunn.’

By the weekend, Mrs Starlin had turned her house into a museum with memorabilia, train tickets bought by the great man, even his bayonet collection, courtesy of Mrs Lunn, whom Mrs Starlin had named prominent contributor on the brochures, of which several glossy copies were arranged in a holder by the front door. ‘Please take one,’ invited the notice above the dispenser.

Monday evening a queue had formed outside Mrs Starlin’s museum. Admission was a reasonable £3.50 for adults, £1.25 for children, OAPs and students, 50 pence. Mrs Starlin sat in her hallway, which was festooned with documents, portraits of the old Bolsheviks, notable Kamenev and Zinoviev before they fell from favour. There were medals and weaponry and pamphlets in the old spelling and dated before the introduction of the Gregorian calendar. Mrs S collected the money and put it in a little cash box and gave visitors a souvenir ticket. Visitors ooh’d and aah’d at the exhibits. Mrs Lunn came by after the opening evening and winked at Mrs Starlin. A man with a handlebar moustache and plus-fours hummed and hawed at the posters, translating them for a pre-pubescent boy who might have been a grandson. He turned to Mrs Starlin and said, ‘I had no idea we had such a prominent historical figure in these parts.’

By the time Mrs Starlin had banked £980, and official-looking visitor turned up. He seemed uninterested in the historical content of Mrs Starlin’s terraced museum. Rather, he went straight up the stairs to a back bedroom, over the door of which was the legend:

СТАЛИН

The official-looking visitor came back down the stairs and said, ‘I’m quite impressed, but there’s a problem, Mrs…erm…Starlin.’ He checked on his clipboard.

‘Don’t tell me it’s illegal to keep my late husband embalmed in my own house!’ Mrs Starlin said.

‘Well, that’s not the issue, Mrs…erm…Starlin.’

‘What is the issue, then!’

‘Firstly, you could be in contravention of the 1973 Trades Description Act.’

‘Trades Descr—?’

‘Indeed. And you have spelt the name wrongly over the door where your late husband’s remains lie embalmed.’

‘You’ve done your homework, haven’t you?’

‘You know that there should be a ‘Р’ after the ‘А’ be there, don’t you?’

‘Yes. So it’ll read СТАPЛИН? But who’ll know the difference?

‘Me. But if you rectify the spelling, we’ll say no more about the Trades Description Act and you’ll be off the hook.’

Mrs Starlin thanked him and said she could give him a guided tour for free.

‘That would be nice, Mrs Starlin, but can I ask you a question?’

‘Certainly.’

‘Why did you go to so much trouble? This museum, the embalmment and all?’

Mrs Starlin explained that her late husband had not done a stroke of work all through their marriage, but since he resembled Joseph Stalin, he might as well earn a living in death posing as the Russian leader, also in death.

Comments (1)

What an imaginative story!