Colorado

I was five when the water finally left us, so I relied on my mother’s memories to make sense of what we lost.

I was five when the water left us, so I relied on my mother’s memories to make sense of what we lost.

She didn’t have many memories herself — for although the water left when she was an adult, it had been in a state of departure for decades leading up to the fact: tides lengthening out across days, ponds drying out into dust craters — and so she told me the same story again and again in an effort to help me understand.

She’d visited the Colorado River once on a family road trip. She was eleven years old. They’d been living in America for less than a year; they were driving across the country for a job her father said was waiting for him in California. And so they drove, all five of them, my mother and her two sisters crammed in the back of their Honda Civic. They only stopped to pee on the side of the road or to fill up for gas. It was the hottest year on record, and all the gas stations were out of ice, and so they bought water by the gallon and let it sit, hot as Hades, in the free space by their feet in the car.

“By the time we pulled over in New Mexico, Ayla, I’d nearly forgotten what cold water tasted like.”

They didn’t plan to stop. What happened was her mother lost it four days into the drive and said she was done, done driving for the day, even though it was only noon, and her father saw the tourist sign on the side of the highway — COLORADO RIVER - KAYAKING & RAFTING NEXT EXIT - and saw an opportunity for a one-hour compromise. As they pulled into the parking lot, he warned over his shoulder, “One hour, okay? Then we’re back on the road.”

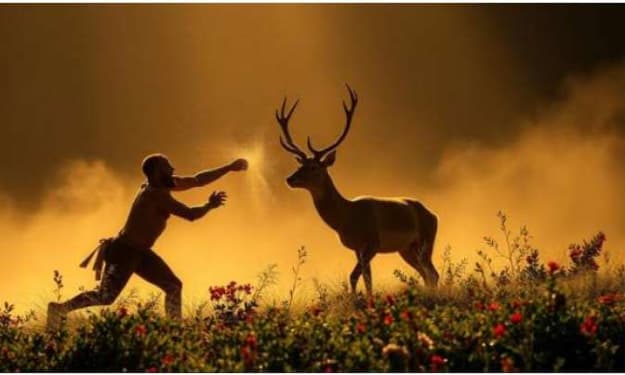

My mother heard the river before she saw it. She turned a bend and stopped short. The force of the water was uncontainable. It foamed and frothed like it was trying to buck something off its back. She was terrified. She couldn’t swim. She almost turned around and walked straight back to the car, but then her father appeared next to her and took her hand firmly in his own. He guided her down to the bank, where her sisters had already rolled up the cuffs of their pants to stand, ankle deep, in the troubled, miraculous waters.

“The water, Ayla. It was alive, like an animal.”

At this point in the story on the one-hundredth telling, my mother paused to cough for several minutes. I watched warily as she rubbed her chest in slow, rhythmic circles. The coughing wasn’t new, but the blood in the tissues was, and so I held my breath as she tried to catch hers.

Finally, she exhaled, long and slow. There was silence, and then her whisper, rough as sandpaper. “It was so clear, that water. So clear I could look down and all see the hairs on my toes. I saw the color of every stone, mija.”

By that point, we were still in our apartment in the South End, and we kept the television on all day long. Below our window stood a ceaseless line of people, waiting for entry into the grocery store five blocks away. Nearly all of them were in line to buy Fabriwater, which came in plastic bottles and was carefully rationed out, three bottles per person per day. The liquid was nearly clear, it was the clearest liquid I knew, but it had a grayish particled hue if you held it up to the light. I didn’t like Fabriwater. It tasted sweet, and left a fuzzy film on my mouth after I swallowed. It would be months before we learned it was just sewage water treated with chemicals, even longer before scientists admitted they were still working out the correct chemical ratio for long term preservation, years after that before the government confirmed what we prayed wasn’t true: that my mother’s bronchial cough was connected to that treated water. Specifically, with the micro-doses of rat poison they used in the earliest batches.

“Anyways,” my mother said. “That was all a long time ago.”

I stared at the suitcase by the door. We were leaving soon for one of the new communities down south. My mother thought our health would improve once we got there, and I was excited, too, because someone on the news had claimed, days earlier, to have seen ice in one of the communities. There were medical units set up in each community. They said the ice was there to sterilize the medical equipment. My mother told me it was a conspiracy theory. She said I shouldn’t get too excited, but she didn’t work as hard as she normally might have to dispel the notion from my head. I’m sure it was easier for her to pack if I was in a better mood.

I was obsessed with the idea of ice. I thought about it constantly. Nighttime, before I fell asleep, I would close my eyes and imagine standing in water so clear you could see straight through to the other side. I imagined the water rising up past my ankles, my knees, my waist, until finally my feet lost their hold and the river carried me away. It was my private bedtime ritual, and it gave me comfort, or maybe just distraction. But I couldn’t imagine a liquid that tasted like nothing, no matter how hard I tried, and this agitated me.

“What did it taste like, mama?”

She was back to packing, now, staring at the folded piles of clothes on the floor by the couch, her eyes making those mental calculations she always made, the ones she thought I didn’t notice. Constant, inexhaustible math equations: how much we needed to survive; how much we could make do without. “It didn’t taste like anything, mija,” she said, distracted. “That’s the point.”

“Everything tastes like something,” I insisted. “You’re just not trying hard enough.”

She’d tried so many times to explain it to me, but this was the night I came closest to understanding. She looked at me, eyes calm and sad, and gave me instructions to find the water.

“Imagine breathing in cold air,” she said.

I followed her orders. The only cold I knew was the damp air of the basement in our apartment building, and so I imagined that basement as hard as I could. I breathed in and held it, cheeks puffed.

“Now imagine the air getting thick and wet in your mouth, until there’s too much to hold and it spills down your throat.” She was crying now, fingers clutching at the locket necklace her father gave her before he died, the one she always promised she’d one day give to me. “Imagine you swallow, and for a moment you don’t want anything else in the world. You’re not thirsty anymore.”

I didn’t understand, she’d lost me at swallowing, but I nodded because I hated when I saw fear in her eyes.

“I get it,” I said, “I really get it. Wow.”

I let her pull me into her chest. Her tears fell hotly onto the neat line of scalp between my braids. I exhaled, and the warm air left me.

I finally learned what my mother meant a year later. We were living in the community by then. There were riots in the cities. The leaders of the communities had promised equity, fair rationing; a cleaner way of living. In some ways, it was better than the city — it was quieter, mostly families, small children running around the tents in packs, laughing and screaming like hyenas — but my mother’s cough had gotten worse, and there was no access to medical aid like we’d thought. In fact, the medical tent was so desperate for help that they hired my mother to help others, to wrap burns and spread ointments while I chased after the older children, desperate for direction.

I don’t know who gave them to her. I only know how kind she was, how she wrapped each arm and leg with the same level of compassion, no matter how many hours she was into her shift. I only know she came home from the medical tent one day, breathless, eyes wider than they’d been in months.

We hadn’t spoken in over a day, not since she came home to tell me she’d given her necklace to a girl my age, a girl she’d treated for burns all over her body. “She lost her parents, mija,” my mother had said. “She needed it more than you.”

Now, she looked wildly at me and said, “Come here, quick.”

I wanted to ignore her, to hurt her as she’d hurt me, but then I saw her fist, wrapped tight around a towel. It took a moment longer for me to register the drips coming from the cracks in her fingers.

“Quick,” she said again, voice rising. “Hurry.”

She held out her palm to me. Two small ice cubes sat like dice at the center of the towel, glistening under the heat. My instinct overpowered my shock, and I ran to her and opened my mouth eagerly. She dropped the ice cubes onto my tongue, and I could’ve cried, because she was right, she’d always been right. It didn’t taste like anything. It was simpler than I’d ever imagined it could be.

And then I swallowed, and the water was gone, and a week later so was she, and I stored the memory of the ice cubes alongside my doctored memories of the Colorado River, which for years now had been dry.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.