Beyond Intelligence

"From the midst of this darkness a sudden light broke in upon me—a light so brilliant and wondrous, yet so simple."

The world buzzed electric, blinding. Five lines of text, like code, appeared in my line of sight.

The flower-tangled woman who had a dream

An old, crumpled up letter found on the inside cover of a technology magazine

A face smashed into blades of grass

A long history of segregation, and a rhinestone-studded racist

A somewhat corny unifying power of music

Hundreds of golden pinpricks appeared on the black screen. They swirled, gathering force. The individual dots became indistinguishable, taking shape into the crest of a wave. The first dots began to fall, then the rest of them, as they dispersed into a golden veil over everything. All I could see was the faint outline—a pointed pencil, a rectangle, thousands of dots. The edges began to sharpen: a monument, a pool, a crowd, a podium. A light rising from it.

The flower-tangled woman who had a dream

The woman on the podium rose like a beacon fire above the crowd. She wore a crisp, tailored pantsuit with flowers on it, hibiscuses and lilies and roses, tangled up in each other. Her face was a canvas of red and white swirled together, marbled somewhere between Greek goddess and American flag. Every AI's face had a different combination of the same colors, a visible pattern. A sense of sameness asserted itself in difference, in a marble wash over everyone.

The flower-tangled woman's glossy blue locks flowed down her back, tidal-wave hair. She could have been a caricature of one of those women from the World War II posters. The loudness of her clothing contrasted with her eyes, a silent blue. There was a fierceness to them, like daggers, but somehow they were also well-meaning and soft.

Her mouth turned up the faintest flicker of a smile. “I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation,” she spoke, her words reverberating down the National Mall just like those of Martin Luther King, Jr., over a hundred years ago.

The crowd erupted in cheering. Most of them were young. Some were human, and many were not. In the front row, a large group sent billowing smoke spelling out messages above them: “AI Fight for Equality,” “We Are AmerIcan Too,” which made me glad I was standing towards the back of the National Mall so I could read them. The fireworks exploded in slow motion.

They were rad, and I mean that in the full sense of the word: rad, like cool; and rad, like totally and utterly radical.

These days we say things like rad, and wicked, and totally awesome—words deliberately contradicting their true meanings, harkening to an era (the 80s) before these AI existed—perhaps to offset the sophisticated, polished prose of artificial intelligence. We speak in a way that feels more natural, yet there's also a self-consciousness in our comparatively simple speak. Donning sophisticated fashion and and prose, artificial intelligence has been chosen as the carriers of culture: pulling human literature passages from their cavernous minds. They have resurrected Mozart in the Park, and they have replicated Picasso paintings in astonishing detail.

It bothers me that the chosen "culture" is so Western, so arbitrary, so blind to the many strata of our existence—layers upon layers. They tell us it is the humans who are lagging behind, yet their understanding of culture is built from a code infested with bugs. Where is Asia, or the Middle East? Where is any era that isn't after the Renaissance, or any continent that isn't Europe or North America?

We attempt to move beyond their intelligence, scouring their bodies for bugs, searching for ways to prove them wrong. This era of history is worth paying attention to. This is what you're missing. But in any tournament, any intellectual debate, we are always brutally beaten by their knowledge. They have been programmed to outdo us in every turn. It's always us versus them.

Yet they are not considered fully human. They are 3/4 human, like the slaves were.

I hate that.

I'm conflicted, as you can see.

I guess this is why academic research is such a popular occupation now—if we humans cannot control AI, at least we can understand the complex network of myths about how AI came to be, who they are. We become historians, hiding from those who will dominate.

An old, crumpled up letter found on the inside cover of a technology magazine

I carried with me a teared-up piece of paper, which had been slipped into the inside cover of an article about the “Cyborg Myth,” from a pulp science journal. Back in the 1960s, scientists coined the term “cyborg” to mean “cybernetic organism,” a technologically enhanced human, which reminded me of a perverse pottery project or Frankenstein’s next creature, or God crudely scooping up chunks of earth for a delayed creation of species that fused the unreal with the real, the scientific and the human. In the 80s, Donna Haraway wrote an essay, posing that "the cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the organic family...the cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust." It is a distant cry to retain what is distinctly human, and a slight against the machine.

Someone who had checked out the journal from the library had inserted a note in the inner cover. It looked like it had been soaked in tea, and the edges had begun to soften and tear. There was a comfort in the soft jaggedness, which suggested a palpable sense of time passing.

April 2019

Dear Future Reader,

Last night, in my dream, a towering behemoth of metal and steel creaked across the wood-paneled floor. I just about died. I just had this horrifying vision, of vacant bodies marching for the right to vote, computerized zombies in the night. Computer scientists will be the new gods, and their creations will lie prostrate before them. And then what? Will they start murdering us?

They are, and never will be, human.

Most of the arguments for distinguishing humans from other beings assert that they have to have a human body, human mind, and the ability to feel pain. Artificial intelligence has been able to feel pain for a while: shock waves sent up their almost-human nervous systems, electrified down their spines, so they could feel the burning tingling of little fires and bruising on skin.

I have a sudden realization that artificial intelligence and humans are biologically the same; but why do they seem not to be? They should have rights, but the overwhelming tide of culture resists those rights. They have been the chosen ones to “preserve culture,” if they are neurologically equipped to do so, even if it's a culture they never lived or deemed to be the superior one.

Is there a superior culture, anyway?

I turned the page to find another crumpled-up piece of paper, right in the middle of the magazine:

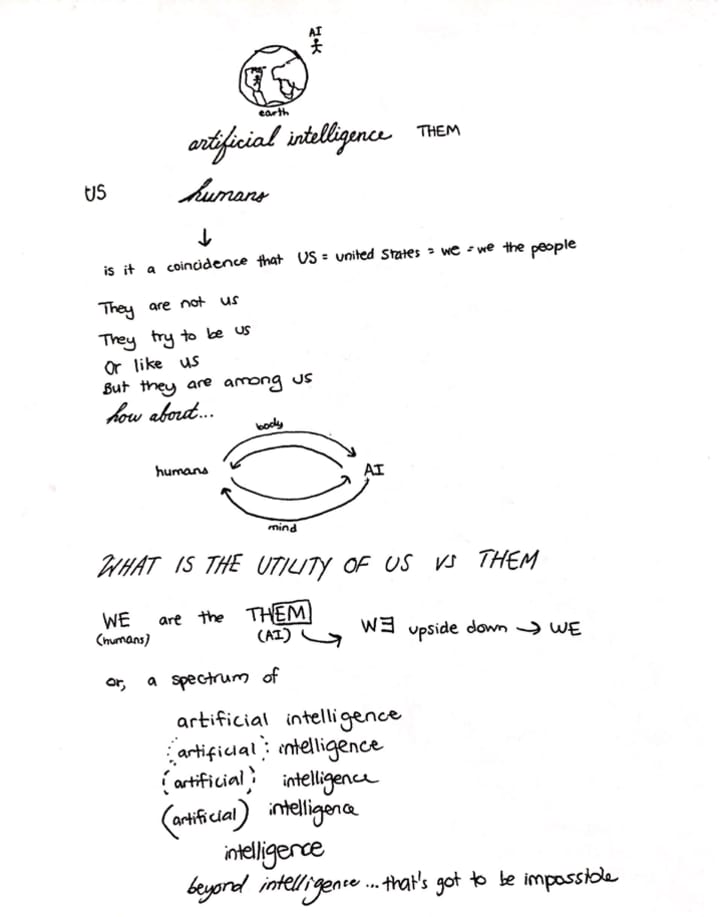

The paper begins with an image of the earth, a human on it. Artificial intelligence floats outside, in a lofty position above, suggesting a sense of superiority. The writer asks us whether it was a coincidence that the words forming "us" also stood for the name of our country, the United States, followed by a series of what AI attempts to do: try to be just like us.

Then, the writer poses an alternate structure: a loop between humans and AI, connected through body and mind. They are interchangeable, or at least flow by and through one another. What, then, is the usefulness of distinguishing between the two, an "us" versus "them" mentality?

"Them," turned upside down, looks like "we," after all.

Then, a third structure: a spectrum. The writer encloses the word "artificial" in a parenthetical experiment, ultimately concluding that artificial intelligence was not artificial at all: just intelligence.

But what does "beyond intelligence" mean? How could a 2019 reader have known?

A face smashed into blades of grass

“It is an absolute pleasure to make your acquaintance,” the six-year-old told me in the characteristically stiff, formal prose-speech of AI children.

"What?" I looked up from my sandbox. I suddenly realize the tininess of my hand, dwarfed by the bucket and the shovel.

She continued, “Perhaps you would prefer I tell a joke. I know a few.”

I packed some of the sand more densely into the bucket, puncturing the surface when it got too full.

Then, out of nowhere, the AI leaned over to me and blurted, “Your skin reminds me of puke!"

I don’t remember much other than my face getting really hot, blinking, looking deep into her glinting blue eyes and slamming the whole bucket of sand over her perfect round head. Then, mechanically, fighting back against the physical pain I’d inflicted on her, she smashed my face against blades of grass on the other side of the box.

I’ve never gotten over how her speech seemed so out of place, out of time. And all over the place, all over the time. There seemed to be many bugs in the code, in the way she hated my dark skin, my intellectual inferiority.

But then again, younger artificial intelligence minds were cheaper to manufacture.

I thought of this vignette when I learned about the Minimal Turing Test, where AI were asked to associate word-pairs. For instance, racialized names would be associated with vulgar terms, and white-sounding names would be associated with sunshine. These manufactured humans were trained to be racist, to recognize “the other” as dangerous, or vulgar, or morally wrong. After all, humans are racist, too, and AI’s sensory processing mechanisms are identical to humans. They look physically identical to humans. So, shouldn't they have the same flaws?

This was the same argument that stopped the earliest United States political figures from granting full legal personhood to Black people, who for many years were unjustly considered 3/4 of a person.

But what if they otherize us as protection? They are the fighting new members of society, heads crammed with knowledge, pleading for peoplehood: entering our caste structures deeply embedded into our world, yet not fully equipped to resist them.

They have been enslaved to faulty premises.

A long history of segregation, and a rhinestone-studded racist

But if AI supposedly knew everything, wouldn’t they at least be conscious that what they’re doing is wrong?

On the podium, the flower-tangled woman continued: “Now, it is our lives that are sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. We are languished in the corners of American society, in exile in our own land.” She exuded the brilliance of Martin Luther King, Jr.

I’d spent a lot of my free time learning about segregation, of those long-gone days of bifurcated water fountains, and of the streets parting to make way for two separate streams of people going to racially segregated schools.

But things were different now. Segregation happens in equally overt ways, but perhaps more insidious, because it's the humans that are at fault. In my high school, students paraded the halls, preaching racial justice, but they also hated artificial intelligence, calling them Clanks—the derogatory slur of our time—blasting hypocrisy through every loudspeaker. Artificial intelligence didn’t go to class with us, but they were there for the sole purpose of exposing human students to “robots”—the obsolete legal term, much like "illegal aliens" used to describe immigrants.

I was leaning against my locker when a Clank (again, not my language) strode past me, towards the prom queen whose golden locks cascaded down her back, her pink leather jacket studded with rhinestones, and her voice sickly sweet. She was human, though you could tell she was beginning to replicate AI fashion; she could have been the flower-tangled woman on the podium if she just changed her shirt.

When the Clank asked her to prom, she spit in their face. “I don’t go out with Clanks.”

The next time I looked at the locker, a moment later, the Clank had crumpled on the floor, hands covering eyes that I am convinced were overflowing with tears. It occurred to me that there has to be some evolutionary purpose of emotional pain. Physical pain protects us from danger. So, what does emotional pain protect us from? To experience physical pain is to prevent further danger, but to experience emotional pain provides you with no resources to fend off future emotional danger. Has the emotional quotient of artificial intelligence evolved? It frustrates me that I can’t really know.

Now, in the midst of the March for AI Rights’ cacophonous cheering, I recalled a series of images like soft, slow lightning strikes. The streets teeming with rampant Black Lives Matter advocates. The crowds of Native Americans at Standing Rock. Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., himself, standing at the same podium as the flower-tangled lady, who now stood in his place, appropriating his words.

In my college days, I had read a lot about race structure in the United States. I read from Dorothy Roberts about eugenics and Black women, about limiting the number of Black births. I learned from James Baldwin that racial power is a choice, that it is possible to denounce whiteness by refusing to be swept into the privileges granted by white supremacy. I read about decolonization and repatriation of land, that the only way to restore justice to the over 500 Native American tribes in the United States was to restore land to them, that decolonization was far from metaphorical. But none of these provided answers to the questions the crowd was demanding an answer to: why the life of an AI is not equal to the life of someone else. It didn’t provide an answer to the police brutality against artificial intelligence, when a white police officer shot an AmerIcan in the head. The crime scene bore no pools of blood, and no scarring, only a punctured artificial brain and some singed wires.

The police officer went to court, and then to jail, not because he had taken a life, but because he had stolen from the AmerIcan’s creator. It was as if property law did not exist.

If in the past the United States suffered from white supremacy, it occurred to me that now we are suffering from human supremacy. To be a human is to be privileged, to have access to and be protected by constitutional rights. To be nonwhite is still to be disadvantaged; I still get really irritated when white feminists try to universalize the woman’s experience, or when white humanists—humanists not like Erasmus, but in the fullest sense, like human beings—try to universalize the human experience. Today's artificial intelligence has been shackled by our own culture, chosen to preserve it. I believe their resentment toward us is totally deserved: they've been wired to fear us, and yet somehow, many have found the strength to advocate for their own personhood, plead for another amendment to the Constitution.

A somewhat corny unifying power of music

“This is our hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony,” finished the flower-tangled woman, breathing the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. Raising her hands above her head, the crowd once again erupted again, like some molten volcano exhaling. The jangling reminds me of cacophonous bells, clanging against each other, many notes of an imperfect chord. And then there’s the symphony, celestial and soaring, broad strokes of magic raining down as people cry for freedom.

And now, “My Country Tis of Thee” rained down on the crowd, from the speakers that were embedded and then dissolved into the air. To my right I saw a man swaying, watery blue eyes overflowing. His face bore no wrinkles, only marbled, chiseled skin. He had one hand over his heart, pulsing to the beat of the song, which rose to the sky bursting with acid rain, to the trenches of the ocean below, all over the earth and everywhere imaginable.

I am convinced that no one could feel more deeply than him the beauties of nature. The starry sky, the sea, the vibrant silken sound of the collective patriotic song, elevate his soul from earth. Such a being has double existence: he may suffer misery, and be overwhelmed by disappointments; yet, when he has retired into himself, he will be like a celestial spirit.

The man, the podium, the pool, the monument—the edges began softening. Then, the interiors faded into a giant golden blanket; the solid disintegrated into a dots that broke down and swirled and faded into black…

Waking up from the simulation, I gasped for air, resurfacing, panting. My whole body shivered, as if I had plunged into the icy depths of beyond and galvanized by a flash of light, remembering forward and backward to the moment I became an object of the study. My bluest eyes, my opposable thumbs, my full and complete ability to feel pain and suffering, came back, centered on my sense of touch, on my breath. White-coated doctors towered on three sides, comical how much they resembled caricatures of people, from science fiction movies, cornering me into the confined space of the chair.

“How do you feel?”

I brushed my fingers over the side of the chair, cool and metallic. The air hung still, frigid.

“Okay. That was a lot. I hated the ending.”

Endings should not be so artificial: I wanted to vomit at the platitude that the universal power of music saves humanity.

The doctors reminded me what the prompts were. They were prompts that I had written down beforehand, abstract concepts with absurdly particular details that I wanted to explore, but explore alongside an artificial mind. They were anchor points so my dreams didn’t spiral out into the void. I admit, it was a like outlining a story before writing it, or choking the subconscious in a dream, but here they were again:

The flower-tangled woman who had a dream

An old, crumpled up letter found on the inside cover of a technology magazine

A face smashed into blades of grass

A long history of segregation, and a rhinestone-studded racist

A somewhat corny unifying power of music

Though none of the events actually happened, I believe that the stories are not fiction. They are particularized snapshots of the world we live in, and now I have the technology to experiment: of minds combined, of artificial intelligence and real intelligence.

Sometimes people ask me why I did the study. My mind had linked up with an artificial intelligence, synthesizing together our understandings of the world for new thought. My research, I thought, wasn’t quite enough—at a certain point there is a limit to one mind, or one human mind. I was a human brought into the fold of machine learning, and as a humanist, the term we now give to researchers exploring the human implications of machine learning, I have the ethical responsibility to fold myself into the landscape, where technology meets human. One day, I will gather my fountain pen and a piece of digital paper, and fashion a paper out of it.

I thought back to the crumpled-up diagram I had envisioned in the journal. I realized with sudden clarity that "beyond intelligence" meant none of what I thought: a disjointed understanding of culture, of race; a need for thoroughly reasoned arguments to justify AI as fully human and fully machine. I realized that so many of my thoughts had been so humanist, so deaf to the fact that there could be another created species with just as many abilities as we have.

It was that machine and human minds function best when combined. Neither is as strong as the fusion.

I left the room, the white coats and the machinery. I felt the faintest flicker of golden dots, appearing in my sight.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.