There weren’t always dragons in the Valley. However, there would be soon, as a king was dying, and the love of his life would soon know.

*

Treol watched the fishing boats and trade ships pass lazily up the River Solm from her high balcony. Even from that distance, she could hear the shouts of sailors ready to land after an arduous passage through the port and its inspections that she governed. Her slave-boy shuffled onto the balcony with her morning tincture of hot sour wine, honey, and spices. She thanked him without looking at him.

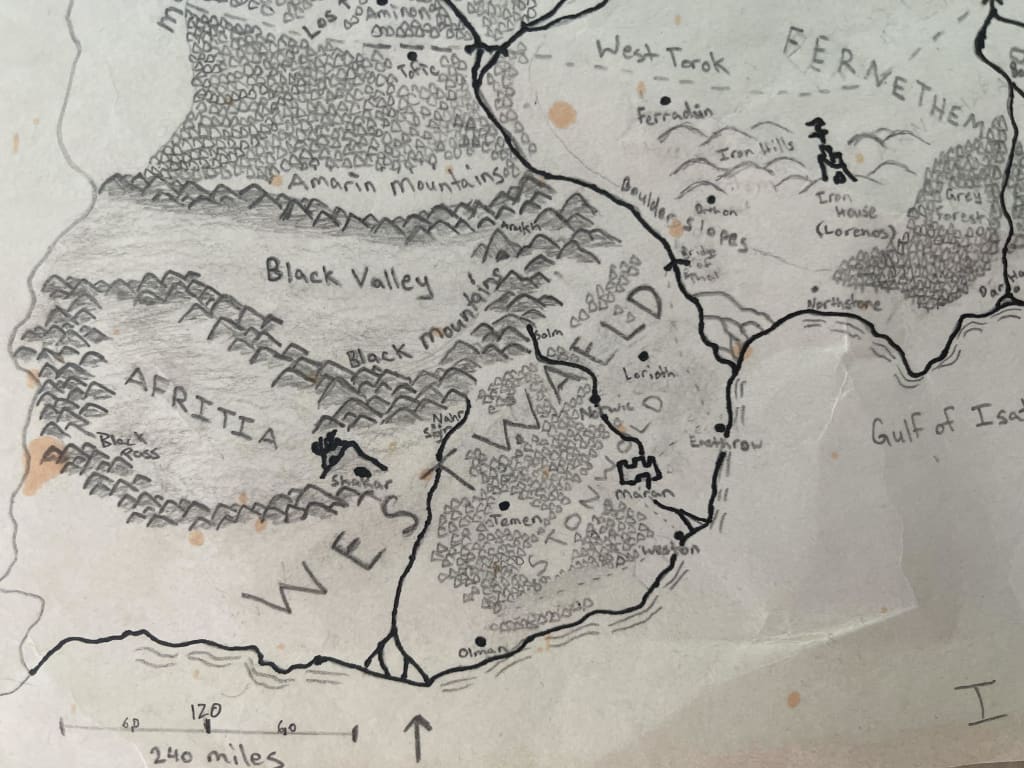

The tower she lived in as Sittura and governor of the city of Weston had an unmatched view of the city and the river. She could see down to the fortress and the city that stretched westward hugging the river, and when she turned her head right and to the East she could see the river crawl to the Port of Weston before it met the murky waters of the Gulf of Isat. She shuddered as a sudden cold breeze hit her neck from the northwest. Bad news always came from that direction, but she hadn’t heard from the capital in a long time. Moreover, there were no ships with blood red sails that signaled the arrive of the king’s messengers.

As she watched the ships, Treol could hear the voices of her two sons, Laengol and Caran below in the courtyard. She could see them, boys becoming men, wrestle with a couple of wild horses shipped in from the kingdom of Fernethem to the north-east. She cringed as Caran, her eldest, was bitten by his horse on the cheek. She waved to one of her slaves to attend to him.

Treol was smiling as she dressed that morning; there was no stark grey sky to meet her, as one often did in Stonwold, and her boys were healthy and thriving. She sat on the balcony and surveyed the city as her slave-girls brushed her long red hair. She even smiled as they giggled at the growing number of grey hairs that were taking over the sheen of fire on her head. She felt a wonderful sense of calm she thought was finally coming to her in her later years.

She’d spent the previous night – and a lot of other nights prior – without nightmares. Her husband, Pongal, had been dead for a few years. Pongal had always been the one to comfort her every time she woke startled from bad dreams. She had bothered him on so many nights with her dreams of blood and destruction. He would listen well into the night, patient, and reassure her.th He would listen until the night he died, even as he was in extremis, on the eve of their fifteenth wedding anniversary.

Treol’s nightmares had been visions of a lot of blood and cleaved faces and mud from a war now long ended. She fought in that war. It was her decision to fight because she loved a boy, a boy that would be king. All that remained at night were her dreams of cleaved faces. Pongal would listen.

“Death all around at such a young age,” Pongal had said on his death-bead. He had been dying for nearly a year, but he was listening to Treol tell him about her dream on that morning and passing.

“Oh, darling, that should’ve been hard. It should’ve been hard.” Then he was gone, but she remained.

Treol stopped having the dreams after her husband’s death. She had feared, right after Pongal died, that she would have no one to comfort her in the wake of her nightmares, that they would come back as strong and vivid as ever, and that he would not be there to tell her “We’re okay now.” But her nightmares never really came back, and she would smile and chuckle bitterly as she thought about that man and their life.

Caran burst into her chambers. He was fighting to catch his breath as his taller brother Laengal came in and smacked Caran on the back of the head.

“I’ve told you not to walk in without knocking,” Laengal said in disgust.

“I told you not to do that,” Treol said to Laengal. Laengal bowed his head and stepped away. “Let me look at you, Caran,” Treol continued as she raised his head to look at the gash on his cheek. It wasn’t deep, but she was worried.

“Where did these horses come from?” Treol asked. Caran giggled and ducked his head from his mother’s hands.

“The merchants said the Iron Hills, mama,” Caran said laughing, his beautiful blond hair bobbing. Treol looked to Laengal for confirmation, and he nodded solemnly. She relaxed.

“Still. Have the physicians look at him,” Treol said guiding Caran towards Laengal’s arms. “And please be more careful, the two of you!” she continued, shooting a look at Laengal. He bowed and hunched his shoulders obediently.

She could hear them both laughing as they made their way down the tower steps from her room and then a sudden hush as heavy footsteps became louder up the stairwell. Heavy, clanging, armored footsteps were making their way up to her. Another one of her slaves rushed in suddenly and told her to hush.

“Sittura,” he hissed, “King Laenin’s messenger!” He darted away into the corner, as the clanging filled her bedroom. But no one rushed in. The metal footsteps stopped suddenly with their feet outside her room. Treol looked out through her open door into the hall flooded with fading torchlight and burgeoning daylight from the many windows. She clacked her tongue at the slave-boy still hiding behind her door.

“Well, you’ve gotten this far without any notice to me, so who is it?” She said as her hand wrested calmly on the sword at her waist.

“You know me, Sittura. I’m Climon, from the King,” said the man in the hall.

Treol took her hand from her sword hilt and ran as quick as she could to the door. She found the King’s messenger, wearing the king’s red color that only he and other close officials could wear, and she recognized him.

“What is it?” She asked.

“He needs you,” he said.

Treol left instructions for the care of her sons, though they were almost 17. She didn’t have time to say good-bye; as soon as she saw Climon she knew she had to leave. She bade Climon stay a few hours and rest, as she knew he’d been riding three days from the Capital Maran with little rest. King’s messengers took ships down the river; they only rode when there was war and an immediate need for the Sitturi of Weston to be physically present with the King. She was the first Sittura, a female lord of Weston, and she would not break that oath for anything.

As she mounted her horse, Caran rushed out to her with Laengal close behind.

“You’ll go?” Caran asked.

“But I’ll be back, by our gods, my love,” Treol said, smiling. She yelled out and the gates were opened. She passed by a small figure of her husband by the gate, next to a larger bust of herself, and waved a kiss to his likeness. Just as she looked up at the overcast sky, a fat raindrop splatted on her forehead. She grunted and dug her heels into her horse, and she was off.

She looked back as she sped away, Caran waved emphatically as Laengal put his arm around his brother and brought his other hand up to wave slightly. She could see Laengal’s face, confused. She turned back to the road when she saw Climon, tall and draped in his blood red cloak, come out to the courtyard to usher the boys away.

*

Laenin was dying. He had known this for months now. Against the advice of his physicians, he left in secret in a grey cloak and hood as a beggar. He limped up the North Road clutching his staff.

It was empty except for a few other beggars that huddled close to the buildings lining the street to escape the falling rain. He smiled as he thought to himself how unwelcome Stonwold was to those who lived outside. The weather was never more than a few minutes away from another torrential rain. The homeless preferred fairer climates in the kingdoms to the north. He gripped his walking staff and made his way to Maran’s outer wall and the Mound Gate.

When he reached the gate, he pulled his hood down to hide his face. He crept to the window of the guardhouse where the soldiers sat escaping the deluge. They were playing a card game at a small table, gambling apparently. He tapped on the glass lightly and shrugged his shoulders in submission. One of the men looked up from the game drowsily and reluctantly, then shuffled his way to the window.

“What? It’s a bit wet to be walking about,” the man said. The beggar shivered and sunk deeper into his cloak.

“I’m on a pilgrimage to the Mounds, sir, for good fortune,” he replied. The man snorted and waived him into the guardhouse.

“The gate’s shut but pass through here.” Laenin obeyed and went through the door. The warmth of the guardhouse tempted him to stay. He hesitated when he reached the outer door, and the man who had let him in dug his heal into his back and shouted, “Get on with your pilgrimage, then, or I’ll make a slave of you, shahat!”

Laenin wanted to tell the soldier that he was a citizen of Stonwold and that he could not be enslaved, as a matter of law. He wanted to uncloak himself and tell the soldier that he was not only a citizen of Stonwold but the First Citizen of Stonwold, the king. But he couldn’t. He went on his way towards the Mounds with the only spirit he had left.

The Mounds were pristine, vacant hills. They were a picture of a distant and forgotten story of the birth of Stonwold. Families would picnic there. Deer and other good game would range on their slopes. There would be times when the deer and elk would come out in such abundance that hunters would try their luck with the gamewardens and hope to hunt without detection, in contravention of law. Such was the bounty – the allure – of the Mounds, at times. Their grasses were healthy and green, stark against the constantly great grey Stonwoldic sky. The rich, black soil peeped through like the night canvass backdrop at Laenin’s favorite play, The Lady in the Great Night.

But Laenin didn’t think back to the moment when Alyssa gave her life beneath a vast and starred night at the feet of her tormented lover, so that he might be sent to the Brighter Hereafter amongst the gods. It was, after all, just a play. No, at that moment, in the cold, damp, and bitter morning, Leanin felt himself transported back to the spirit of his most ancient ancestor: a king, a forbearer, he only knew by songs and history books.

Laenin gazed far up at the temple from the foot of the Godsmound while he caught his breath, resting his hand on his right knee, the other clutching his staff. He peered far ahead at what seemed the crown of the Godsmound, miles away. The old, forgotten temple was ever in his sights.

It was no great temple. It had stood upon Godsmound for millennia, a single chamber stone structure that was not larger than most houses. Inside there were no priests sacrificing at an alter, no great effigies to any of the gods, and no great mosaics or tapestries to adorn the divine house. There was only the damp earth for flooring, rough walls hewn out of dark stone, and a great domed roof that capped the circular chamber. There was a single crude inscription in a long-abandoned alphabet above an arched niche carved inside the chamber that read, alrahman – the name of the most ancient god of Stonwold. He was the god of eons ago forgotten, if not altogether erased. The Stonic people never uttered his name nor made supplication to him. But his temple had withstood time and war.

It was outside the protection of the modern pagan kings, including Laenin, and it remained only as a relic visited by peasants and nobles alike. For a long time, kings would recite that Alrahman would protect his temple himself, and if he could not, he was likely dead. And so there would be no need to worry or expend public resources to preserve it. Thus, the temple served simply as a landmark, a reminder to all, that the Stonic tradition considered the Mounds hallowed ground. That and that no king had thus far dared to defy the law that these profitable and fertile hills should ever be exploited in any way. For thousands of years, nothing could be grown, hunted, or built on these hills. Beyond that, however, no king bothered himself with the temple or the Mounds. No invading army expended time or energy in bringing about their destruction. And so there the ancient temple stood.

Laenin, from the time that he was thirteen, had an academic interest in the temple. He had studied its form, cleared away the layers of moss that covered the inscription and wondered at the markings like a historian of ancient worlds lost to everyone. He had marveled at how the rains and snows and winds had smoothed the outer stone of the temple, but which did nothing to undermine the temple’s structural integrity. It was Laenin that had deciphered what the strange inscription spelled: the name of a dead god he vaguely remembered hearing about from his tutors: alrahman. The philosophers knew very little about the nature of this alrahman, but they believed him to be the unrefined, crude god of ancient and simpler times when people worshipped trees and rocks. They maintained that the temple’s state reflected their hypothesis.

Laenin was never impressed with his tutors and priests’ historiographical abilities. Their affinities brought them closer to the occult than to any meaningful discussion regarding truth. Thus, he was a difficult king. Soon after his mandatory studies with the philosophers and antiquarians were done, Laenin began to regularly walk up the Godsmound and enter the chamber of the ancient temple of alrahman.

Laenin had placed a wooden stool in the niche under the name of the unmentioned god, alrahman. He would sit on that stool and stare up through the oculus. The oculus, so focal to the monument, was nothing more but a round hole in the center of the dome of the stone hut that allowed sun, rain, snow, hail, dirt, or any filth down into the temple. Once, during a time of locust plague, the interior was filled with them. But even in the worst conditions, the king would sit upon his stool, where the king could be close to the earth, close enough to smell the damp soil, to hear the falling rain upon the stone, and remember.

It was in that place that Laenin intended to die.

Laenin did not, however, account for his own failing health. Although he had intended to wait upon the wooden stool in the temple, the cold air made his breath short, and his frailty hindered his progress up the slope. The damp grass soaked his feet through his sandals, and his steps faltered. His staff sunk deeper and deeper into the soil. The morning was giving into midday, and halfway up he turned around and looked out onto his kingdom.

To the south were the walls of Maran. It was mostly a low built city, unlike most of Stonwold’s great cities. It was almost a great spiral, broken in half by the river that wound down from the mountains to the north all the way south and east to the port of Weston. The outer curves housed the jutting spires of the great temples. Looking down from that vantage point, Laenin could see the walls, the spires, and the low center that comprised the old city. It struck him that the humble beginnings of the ancient Maran reflected the temple atop the Godsmound.

To the east the midday gloom rolled over gentle country slopes, and to the west the land was swallowed up by the Forest of Thelingen. Buried deep within that forest was the place where Laenin’s reign began. He thought on it and how that not once during his long rule did he return to the old fortress where his reign started and his love ended. He stared hard across the country at the first shrubs and trees of the forest, as though to pierce back through time to his youth.

He then heard the drumming of hooves from the east. He turned, expecting to find Treol, but was faced with a mounted company flying his insignia. It was the maratin – king’s guard. Riding at the head was his son, Latharon.

The Maratin slowed as they approached him, but Latharon continued in his pace up the slope to his father. Laenin stood and fought to catch his breath before any could reach him, his pants showing in the air. Latharon dismounted several meters away from where the king stood. He bowed his head and removed his helmet as he moved closer to his father as if he was a skittish horse. The Maratin remained on their horses, staying silent as to hear what was to ensue.

“Aba, you cannot be here,” Latharon said softly. Laenin studied his son, his shaven face and peculiar grey eyes and thin brow. He remained silent. “Aba,” his son began again, but before he could continue Laenin spoke.

“Whom do you serve?” Laenin said loudly and sternly in the direction of the Maratin. At once they each sat up in their saddles, hit their leather armored chests with their fists, and replied in unison, “The Lord of this House!” Laenin straightened his back, tightened his grip on his staff and gave his guards a piercing and fierce look.

“And who is the Lord of this House, maratin?” he commanded. At that moment all twenty Maratin leaped from their saddles and dug their spear tips into the ground. With a practiced orchestration, they beat their chests in unison and shouted, “Laenin! Laenin! Laenin!” The king looked back at Latharon and relaxed his stance.

“Who among you then, will take me to see my lord?”

Latharon shifted uncomfortably and looked to the ground before he spoke.

“Aba, I’m only afraid for your health. I did not mean to presume to command you. I am your son,” he said vacantly. Laenin remained indignant.

“Who among you will take me to see my lord?” He repeated. The Maratin each bowed to their knees in utter obedience. Latharon mimicked the same.

“Surely, we can, Aba,” Latharon said through gritted teeth. Just then, the distant rumbling of hooves came to them, and the Maratin instinctively sprang up, pried their spears from the ground and faced the noise.

“Easy, now. That will be Treol. Do you remember Treol, my son,” Laenin said with some contempt. “She has come to see me on my way,” he continued. At that moment, a strange feeling came over Laenin. It was a sudden embarrassment at his current state, muddied and haggard, with his most beloved servant approaching. It had been years since they had seen each other, and he knew with his sickness and age that he had not fared well. She, on the other hand, remained as strong and healthy as he had ever known, as he could see with his one good eye. The Maratin relaxed their stance, though still vigilant, and Treol threw herself from her horse and left it to be wrangled by one of the guards.

She was the same age as Laenin, 83, with her red greying hair, and strange blue eyes and she threw herself at him like a teenager would with a great hug that almost broke Laenin’s fragile frame. She propped him up and looked him up and down with piercing sapphire. She had lost none of her youth or vigor, with a smile brighter than the first day.

“You grew a beard!” She exclaimed. Immediately, Laenin began to tremble, his eyes glistening.

“I think you know,” he said coyly, “There isn’t a man in Stonwold who doesn’t have a beard because of me.” He could not bring himself to look at her; his eyes were fixed to her muddy boots. Treol felt the king’s shame. She turned to Latharon, clean shaven, and waived him away along with the Maratin. The Maratin shifted uncomfortably until Laenin raised his hand slightly and flicked it towards the city. “You’re relieved,” he said. “All of you.”

Latharon returned to his horse and grumbled. “Latharon, king’s son, may I call on you this evening?” Treol called after him. He grunted as he mounted and replaced his helmet. He stared down at the pair of them. He seemed to compose himself. Suddenly, he whistled, and his horse slowly brought its forelegs down to bow, his favorite party trick.

“Sittura Treol, it is always my greatest honor and pleasure to be at your service,” Latharon said with a good degree of charm. He turned and waived the Maratin with him and they galloped back down the Godsmound to the city. Treol and the king stood and watched as his bodyguards rode away.

As soon as they were out of earshot, she turned to him and tugged his beard and said, “What are you doing out here?” She hissed gently. “Your poor messenger nearly died coming to tell me that you’re dying, as if I didn’t know.”

Laenin shifted uncomfortably before the woman he had loved since he knew what love is. Treol softened but said nothing. The winds picked up and a downpour began. Treol picked up Laenin in her arms amidst his protests and placed him gently in the saddle of her horse.

“My lov– my king, I’ll take you up to your damn lord.” And she did. As they climbed, very little was said. Laenin sat in the saddle, collapsed and embittered by defeat. Treol thought it best to leave him with his thoughts for a while. In any event, she was enjoying the excruciating climb. They went on that way for some time.

“Leave it to the Stonic people to call these things ‘mounds,’” Treol said breathlessly, breaking a long period of silence. “How you thought you’d make it up alone…” She said with a grin. Laenin felt her humor, even as he stared at the back of her head as she led him and her horse up the Godsmound. He could not help but feel the sun-shine upon his heart that she had made herself happy, even if at his expense. He bonked her on the head with his staff and laughed as she cringed.

“Last I checked, we were the same age, Sitturia,” Laenin said. Eighty-three years. Seventy-five years I’ve known this woman. Treol laughed slightly but said nothing. They had reached the temple.

When Laenin saw how black the stone was, he remembered how far away the stone was away from its quarry.

“I keep forgetting,” said Laenin.

“What?” Treol answered, as she peered up at the dome that extended 30 feet above the ground.

“How far away this stone is from its quarry. How could Aroben, my ancestor king, have made this?”

“Please. No more of Aroben or his God. I still remember you, small and freckled, chattering about the alrahman and this damn temple,” Treol said with nostalgia. Laenin was silent. He simply meditated and watched the temple. “I’m sorry, I didn’t mean—”

“Do you remember my father’s parties, in the temple Avianmarka?” Laenin said suddenly.

“Yes. Of course. They were when we first drank wine,” she said with flushed smile, ducking her chin into her shoulder as she was accustomed to doing.

“When I saw my father, my mother, my sister… There was always something in me that found it all too...”

“I know, Laenin, I know. But they’re a part of life. Stonic life.”

“I don’t want to change Stonic life,” said Laenin. He sighed deeply and crutched his way up to the temple. He could hear his joints clack and his bones creak as he walked up. He looked to Treol and touched her arm. “Sittura Treol, I mean to save it from extinction.”

As they walked, Laenin could sense Treol’s discomfort. He noticed the glisten of a tear on her cheek, and he sensed her regarding him with an effort to avoid detection.

“The illness, my physicians tell me, should have claimed my life years ago,” he said with a warm reassurance. “Alive, still, but not quite the same,” he said, smiling. Her grip tightened softly around his arm. He patted her firmly on the shoulder.

They reached the temple at mid-afternoon. It was no longer raining, as Laenin had hoped it would be. They stood before the arched hole that was the entrance and smelled the ages. Though the world had changed around it, though the ages had flowed tumultuously, the temple of alrahman held the air of history, the one true ether.

Laenin had been there many times, so when he left Treol to enter she flinched and fussed uncomfortably. She watched him disappear into the dark chasm of the entrance and remembered the valiance of his youth.

“Come find me, Treol. There aren’t many places to hide in here,” said Laenin from the darkness. She edged forward and felt herself consumed by an almost visceral discomfort; this was foreign. When she crossed the grassy threshold, she was surprised to find the King of Stonwold naked, sitting on a stool. She was more surprised to find that two priests, naked as well with their long grey beards and faces painted with white limestone chalk, standing beside the King.

The oculus, the hole in the center of the dome above, let the sun’s faint rays alleviate the darkness. The sun showed the naked king of Stonwold on a wooden stool, his two lime-paled priests standing beside him, and a boy holding a small torch, a flame striving to remain alive in the close quarters of the chamber. Treol began to tremble before the godliness of the sight in the dark, as if she had stepped into one of Stonwold’s greater temples and beheld its majesty.

But it was rank – damp. It was simple. It was not worthy of gods.

“Do you know who these priests are?” Laenin asked, in pain. His frail body had been shed of all furs, and his ribs and flab heaved in and out tiredly. He shook.

“Abakabar, fathers and priests of the elder gods,” replied Treol. She trembled, expecting a death ritual.

“Abakabar, elderly fools, leave,” Laenin commanded promptly. Trembling, the the priests scurried, having been prepared to give their lives to accompany the soul of their king, as was sometimes – oftentimes – required by a king. Laenin smirked and shrugged his shoulders

“Do you know who this is, Sittura Treol?” Laenin patted the boy’s head as he asked.

“My lord, I observe the customs of kingdom, but – “

“Ah, but what, Sittura Treol?” Laenin interjected. “But you would rather not be a part of these traditions? Correct? Where a young boy is burned alive to light my, the holy gods’ King’s way to the End World?” Laenin continued. He patted the boy once more and took the small ceremonial torch from his hand and flung it against the stone wall of the temple. It hissed out in the damp of the chamber.

“Bounyahoor!” Laenin exclaimed, and the boy jolted and eagerly left the temple. “When did we become fire worshippers, Treol?” Laenin sat on his stool and studied Treol as she examined the temple. She was busy studying its innards, removing her gloves to run her fingers against the smooth, dark rock, and breathed in its damp ancient air. He could see that she was hesitant and nearly dismayed.

Laenin had written to her many times over the decades to describe the feel of the black stone and the shape of the dome which capped it. She had often found it peculiar, Laenin’s fixation – his obsession – with the old ruin. He wrote about it like a young man would his lost lover, longingly and with exquisite detail. And although she had been to Maran many times to have an audience before Laenin, he had never brought her to see the temple until that day, nor had she bothered to visit it of her own volition.

But now that she could see it for herself, standing in the round chamber with the grey light shining down from the occulis, she could see no purpose or profundity in its making or design. It inspired no awe, no feelings of humility before the grandeur of any god. She saw an abandoned stone hut where primitive chieftains had once stood and worshipped a long dead god.

“What are you seeing?” Laenin asked. Treol was circling the circumference of the chamber, running her hand against the wall. She paused at the question and smiled the smile she has when her own wit amuses her.

“The object of your affection for so many years,” she said. Laenin coughed a chuckle and collapsed. Treol lunged from across the way. Laenin’s body crumpled to the floor as he coughed and coughed. As Treol rushed to his side, she whimpered faintly before Laenin’s chuckle resumed and resounded throughout the chamber.

“The object of my affection,” Laenin gasped with a crazed air. He coughed some more and brought a rag to his mouth. As it had been for more than a year when he brought a rag to his mouth, there was blood. Blood enough now, though, to stain the rag and remain on his lips. Treol snatched the rag away and studied it. She trembled as she smelled the metallic air. She saw her fears confirmed; Laenin saw what he had already known since his diagnosis.

“King,” Treol began while cradling Laenin’s head like she did her father on his deathbed. Laenin waived his hand in the air dismissively, stopping her from continuing. The chamber went silent except for the rasping breath of the dying man.

Laenin’s head shook slightly as her body trembled. As he lay dying, she felt his hand reach up and grab her, then tap her, on the shoulder. He continued to motion and Treol could not understand. He was almost flailing while he was trying to speak but only gasps came out. Then, after a good while, the words came.

“Lift me… to the chair, Treol,” Laenin let out, annoyed. She did quickly. “Idiot,” Laenin exhaled. She laughed as she wept, remembering the way he was when others did not catch on to his meaning, his point of view. Impatient, irritated, and understanding.

Laenin sat on that stool. He sat on the stool that he had maintained for a quarter of his life. The stool that no one knew about, in the temple that no one cared about, to die in a way that no one had died in a millennium. He sat and was content.

“Did you just want to see me again, Laenin?” Treol asked. Laenin perked up suddenly, some blood dribbling out of the corner of his mouth into his beard. He shook his head from side to side with a cheeky knowing.

“No,” he whispered. He sat on the stool while Treol propped him up in her arms and found the words. “I think it is safe to say, my best friend, I’m gone soon. I know I need, as king, I need two witnesses to recommend my succession to the Sitturiate. You’re my first witness, Treol. I came here to die in the sight of our forbearers and the one old god. I came to make you my witness that: Latharon, my only son, will not be king. You will relay, with all the weight of your office, to the Sitturiate, that the next king of Stonwold will be elected by the Sitturiate, without my son Latharon as a candidate.”

Treol went blanch white. It took all her strength to remain silent and to keep herself from trembling in fear. She shifted uncomfortably as Laenin nodded off on the stool, naked and feeble. She sat there for a moment and breathed.

“Laenin… Laenin,” she whispered. “Please be awake.”

The King, like the hardest oak that had ever stood in Stonwold, was upright, alert, and naked and continued, “I give no power to Latharon, my only son, and trust Treol, issue of Greol the Fishmonger, with the affairs of my country.”

“But Latharon – ”

“Must not rule,” Laenin interrupted. Treol clenched her jaw. She took several deep breaths and looked around her. The dark chamber of the temple yawned at her, the light of the occulis pierced into the darkness. Treol searched her mind for the words to stop the madness of her king. Finally, it came to her.

“The second witness, Laenin,” she said. She searched around the chamber for a hidden witness, but there was none. Laenin grunted. She looked to him almost joyfully before seeing that he had a wide grin of knowing.

“Climon, are you here?” Laenin bellowed. There was a long silence, and Treol sighed with relief before she heard the sound of muddied sandals and the clanging of chainmail approaching from outside. Treol looked to the doorway to see a silhouette appear at the doorway, a caped figure, tall. He walked into the shaft of light and Treol recognized him at once.

“This is the messenger that bade me here,” she said. Laenin nodded.

“He has ridden twice as long as you have, Treol. For Climon, it’s been twelve days riding and six horses, all to bring you here to be my first witness, and so that he will be my second witness. After you, I don’t think I have a better servant,” Laenin said. Climon cleared his throat as he entered the temple. Laenin smirked and said, “Or perhaps before you, Treol.”

Treol studied him. She was sure it was the same man that had bid her ride to Maran in the name of the king. He wore the crimson color reserved by law under penalty of death for the king and his closest servants: his messengers, his advisors, his physicians. The color of Climon’s cloak spelt death to anyone that interfered with his business, including governors of Stonwold’s great cities, like Treol. Beyond that he carried the seal of the king.

“This man is my friend, Treol,” Laenin said, reading Treol’s suspicions and jealousy. He waived Climon over to his side and said, “Did you bring the wine?” Climon nodded and produced the leather bladder from his side. He passed it to Laenin who waived it away.

“Twelve days riding, Climon. It’s for you,” Laenin said. Climon, without hesitation, uncorked the wine sack and gulped it empty. Laenin trembled as he got to his feet; the other two rushed to lift him.

“I’m just giving him my seat; I’m not dying!” Laenin shook himself away from their grasps. Climon hesitated before Laenin threw him a stare he reserved for men he executed for treason. He sat immediately. Treol remained speechless.

“I have brought you both here, to witness, my proclamation. To witness my rising to the Kingdom of Glory with the One God,” Laenin began. Both Climon and Treol exchanged glances. Laenin saw that they were nervous. He let out a scream like the mad man they thought he was, his frail body trembling as he did. Climon moved to secure him, but Laenin continued, screaming.

“But more importantly, my servants, I have brought you here to make one thing known. One thing. Latharon, the man that you know as my son, is of my blood. He is as much a product of my loins as I was of my father’s.” He bathed in the light of the hole in the roof. Naked, naked, naked, he stumbled with his arms open to the sky.

Climon and Treol shed quiet tears, seeing a frail man give all his strength to a final thought that made no sense. It was a thought (to them) free flowing, apart from real life, devoid of any context. Then Laenin stamped his bare foot into the dirt of the temple’s floor. There was dew in his beard, and sweat clung to the naked bones of his body. Both Treol and Climon, who were both hard people, could not control their grief as they watched a man they loved descend into the delirium of death. Then their grief caught Laenin’s attention, and he stamped once more, and the earth seemed to shake. And then Laenin was lucid.

“Just know this, you two: Latharon is not of mine for kingship nor for this country. I have seen it. The elections of our Sitturiate have been, since its reinstatement by my father, largely ceremonial, I know. But now, I know that boy is not fit to be king of Stonwold. He will rage on this good country a hurt that has not been seen in the history of Ard, ever. You two are the only people in my kingdom that I can trust. Work together to keep Latharon from being appointed to the kingship.”

It took eight hours for Laenin to die, time enough to have his physicians look over him. Treol and Climon both sent for them each by name, and each refused because of the warning Laenin had given them before his departure. “Not only yours, but your families’ and the lives of anyone who even looked at your families will be forfeit.” Laenin had the means to make such arrangements even after his death.

So he sat naked, and the rain began to drizzle, and Treol and Climon sat by him on the bare earth. They would glance at each other, then at their king. At times they would stroke his beard and they would talk and laugh together. But death clung over the gathering, and Treol and Climon could do nothing but wait.

And then he died. Treol was reciting a poem from The Lady in the Great Night. As she recited, she felt his breath give out while his head was cradled in her arm. He dribbled blood. She wiped it away and picked his featherlike body up from the stool and laid him on the cool dirt of the old sanctum. She and Climon prayed over him, with supplications to their gods and the old god under which Laenin chose to die. Both of their minds, however, were whirling in their flaccid attempt to maneuver through the future. One thing was certain, however, there would be dragons in the Valley soon.

About the Creator

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Masterful proofreading

Zero grammar & spelling mistakes

Comments (1)

Great first chapter! You have a talent for story telling.