A Glimpse into Village Life 75 Years Ago

Childhood by the River

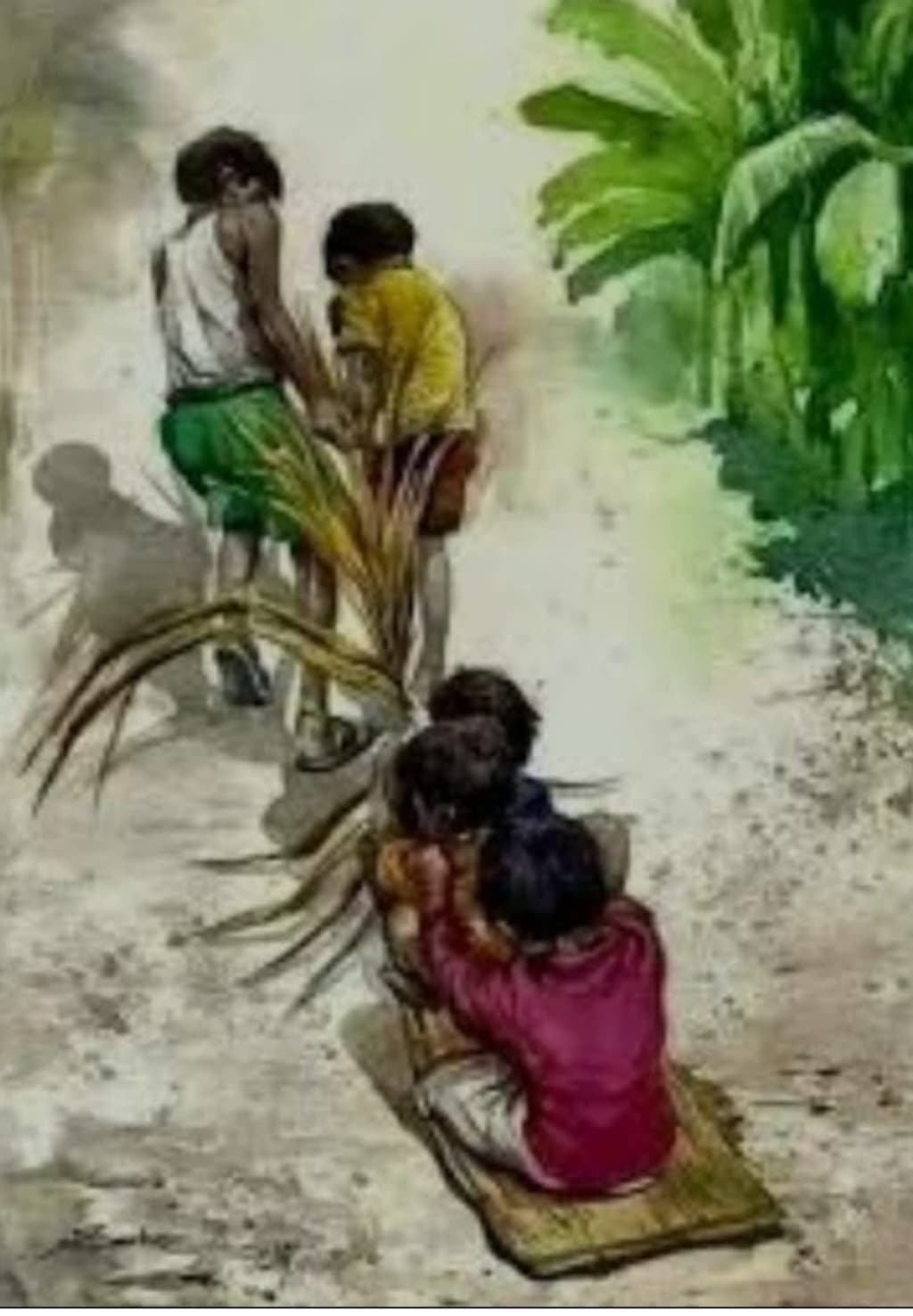

Back then, children in villages had a playful childhood because there were no tutoring classes.

This is about that childhood about seventy-five years ago.

There was a stream that flowed through the middle of the Ahangama Goviapana village where I was born. Some called it a river. It had no name.

On Saturdays and Sundays, we spent our time by the river. We did not feel afraid because we had uncles who fished. During the rainy season, the river was boiling, which brought us great fun. When the elders of the village got together and took a few reeds and made a wall, we little ones were also allowed to climb on it and swim in the river.

Some children went into the water to play after taking off their sarongs and putting them aside. They did so because they were afraid of being scolded by their families if their sarongs got wet.

Even Montessori children today wear underwear, but we didn't have them back then. Even though there were girls of all ages playing naked in the places, it wasn't a problem for anyone. Even girls in grades three, four, and five sometimes played naked, but there was no sexual abuse like today.

When the river started to rise, in the evening, the older men would remove the sand that had settled in the estuary, or Modara, where the river flows into the sea. We called this moidara cutting.

When the moidara was cut in the evening, some people would go the next morning to collect the fish that had settled on both sides of the river.

When the sea water entered the river, the fish in the river died. Sometimes, sea fish and river fish died on the seashore. One day, along with the other children, I also collected some of those fish and took them home. Hearing that, my mother threw away the fishing line and warned me not to do that again.

I have another memory with that river.

On both sides of the river, some people had built fences around the river and built grates.

The coconut husks brought from the coconut husking places are put in the grate and coconut branches, coconut bats and mud are placed on top of them and the coconut husks are allowed to rot.

The men who have removed the husks that have been rotting for months are washed in the river water and dumped.

Then the women put them on a log and beat them with a strong stick. The coir is spread all over their bodies. The women wear a strange dress. They wrap another cloth over the cloth they are wearing, as if they were wearing a day cloth. They sit on the ground and sometimes continue to beat the coir all day long. The coir left in the places where the coconut husks are being crushed is put into the stove. The coir is sold. Those who buy the crushed coir take them home and dry them in the sun. Then, both men and women would spin ropes at night.

In the past, everyone spun ropes by hand. Around 1954, hand-held rope-spinning machines arrived in our village.

These rope-spinning machines were two devices that could be pushed back and forth, like two bicycle wheels. Three people were needed to spin the ropes. We also joined in by turning the wheels by hand for fun.

There were places in the village where you could buy ropes spun by hand or by hand machines. Ropes were sold by the pound. Several women in the village would gather at one place and spin ropes until midnight.

Our mother would also buy them from the coconut husking place and spin ropes by hand in the sun. As soon as we got home from school and had lunch, my sister and I would eagerly take bundles of ropes to sell. We had to walk about a mile.

We also received five cents each from the money we received from selling ropes. At that time, a sugar bun cost five cents. We put that money in a box and used it to buy school supplies and books when needed.

At that time, our village had three radios. One was in the temple. The other was in the library. Another was in a house in the village. Every Sunday and on the full moon day, adults, men and women, gather at this house at eight in the morning to listen to the sermon.

The radios, placed on a white cloth, were placed at the door. Some sat on the floor and listened to the sermon. Several children from the village came to listen to the children's sermon at 5:15 in the evening. Children's sermons were reserved for seven days of the week. On Sunday, it was the Saraswathi sermon conducted by Mr. Karunaratne Abeysekara. On Tuesday, it was the drama program called the Children's Theatre conducted by Mr. Sarath Wimalaweera. The program was run by Guruda Karunaratne Abeysekara. When I was in the third grade, I once mailed two poems to this. It was said to be a successful essay, but it was not published.

On another day, not only were both poems read, but I was also encouraged to continue writing.

All the children shouted that two of Rane's poems were lost. After the program ended, the village woman told me

"That child should not come back here, tell your father to get a radio."

When my mother, who said she was jealous of me, told the temple monk this news, he told me to come and listen to the radio anytime.

Comments (2)

Nice work

Very good work 👏