I remember very little about the days after my mum died.

It wasn’t a complete surprise of course, she had cancer, and the last time I saw her she looked incredibly frail. But even though we knew it was coming one day, I didn’t know it would be that day, and the call from my brother at 5am was more shock and silence than it was talking.

I remember my dear friend, Rebekah, coming round to my house just to sit with me. Then there were several days back at my dad’s house (dad’s house now, not my parent’s house) trying to help with the practical stuff, ringing people to tell them the sad news. I remember one day where I rang a whole bunch of people to tell them, and how I felt progressively numb, like my telling of the story was becoming increasingly rote, devoid of emotion. There is a whole other kind of tragedy about the way, with such huge and terrible news as losing your mum, how quickly it is a thing that happened. Just another thing. An event.

My dad offered to pay for a holiday, if I wanted it. A break, some space. I took him up on the offer, but I’d never been much good at having actual holidays. Somehow, I didn’t know what to do with them. I do love learning though, and I’d had in mind to study with a particular martial arts teacher in Paris, so I decided to get in touch with him and see if I could go there and train intensively for a week. Maybe the change of scene would help.

So it was that I found myself, two weeks after the funeral, on the Eurostar train to Paris. I felt a rush: I was going to learn from someone who had loomed large in my imagination since I first read about him in a book on internal martial arts masters. There was also an intensity to my emotions that meant everything felt almost painfully immediate. It wasn’t grief - in my experience comes later, it takes time for grief to arrive - this was my psyche rubbed raw by pain and sadness too big to feel right then.

My mum had, had a bit of a ritual. We never talked about it, beyond me thanking her each time, but she was quietly consistent about it. Each time I returned to our family home – in the holidays between semesters at University, or coming back to visit, once I lived in Brighton - there would always be a bar of chocolate and a new notebook on my desk in my bedroom. I’d always loved chocolate and writing, and this was one of the many small, thoughtful things she did. It had often struck me how fascinating and symbolically right it seemed that her work had been as an expert on the heart – medically speaking – but her gift as a person seemed to be a parallel mastery of the loving and thoughtful act. She was far from perfect, but she was deeply caring: a heart expert in every way.

I sat on the train to Paris, with the last of these treasures in my bag. I hadn’t been able to bring myself to eat the chocolate yet. It had never occurred to me that perhaps she replaced the bar and notebook after I left each time, rather than doing it in preparation for my arrival. Maybe there had always been these little gifts, these messages of love, waiting for me, whenever I wasn’t there. Somehow, she’d made sure that even after she was gone, I’d come home to one last gift. One last moment of experiencing my mother’s love.

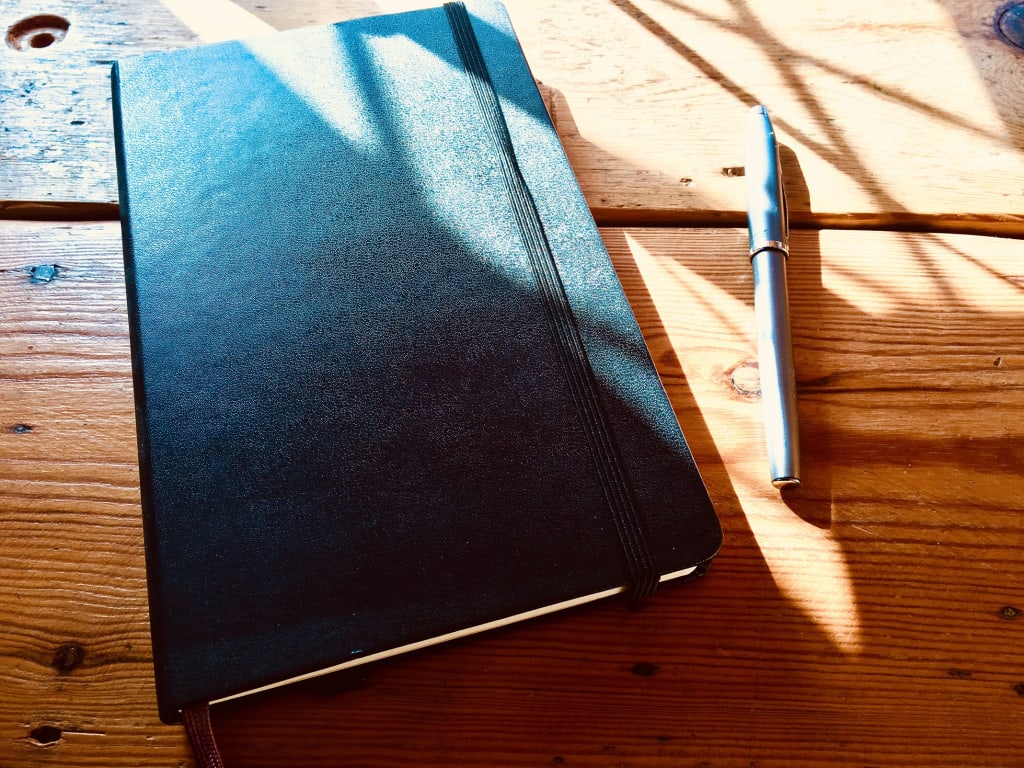

I took out the notebook. It was my favourite kind: simple, black, hard- backed, great for writing on the move; the heavy cream pages feeling like they should be used carefully, not scribbled and scrawled on but filled thoughtfully with graceful phrases. I knew there would be a little pocket in the back of the book for storing notes or other useful things. I’d never really used that pocket in these books, but I loved the idea of it. It felt like it hinted at mystery and adventure somehow. That might seem silly, but it was like when you were a kid and you first discovered a coin pocket on a pair of jeans. Something about that little pocket met and merged with your imagination as a child and it became a spy pocket for concealing secret messages, or a pocket for hiding a magic amulet, a place to keep tiny treasures – the safest of places for the most precious of things.

I placed the notebook on the table in front of me alongside my fountain pen, also brought for me by my mum, another talisman of her care. I’d been planning to write. Maybe start a story, capture a phrase, or let a poem flow from my fingers… but there were no words in that moment. I watched the Kent countryside flicker by the window and took a great, shuddering breath. I’d find words later, perhaps.

I arrived in Paris Gare-Du-Nord station and felt instantly overwhelmed. I had slept for part of the journey, the last couple of weeks had been filled with unintended late nights and broken sleep as my subconscious sought every which way to make sure I was too tired to think or feel too much. Now I was in a hectic metropolitan station, unfamiliar and full of signs I could only half read with my minimal French. I took a steadying breath and remembered my Uncle’s advice at the funeral when he heard I was going to Paris. He’d lived and worked in France for a number of years and told me not to get an A-Z Map (this was before the days of smartphones and Google Maps), but to buy the ‘Paris Pratique Par Arrondissement’. The zones in Paris are arranged in a spiral and the Paris Pratique made it much easier to navigate. I bought a copy and felt instantly more confident. I still didn’t really know where I was going, but at least now I felt equipped to work it out.

I’d found a cheap hotel in the Latin Quarter, as central as I could get without being extortionate. I had remembered liking the Latin Quarter best when we’d visited in my early teens so had picked this place on that basis. I got there without any great difficulty and arrived in what felt like blessed sunshine on a little, cobbled street with a distant view of the river Seine.

The hotel was pretty run down and more like some old apartments than the hotels I had stayed in with my parents, growing up. The room had bare floorboards, a rickety wardrobe and a steel-tube single bed, but it was clean and had a tiny balcony door onto the street. “Balcony” makes it sound much grander than it was. In reality, it was more like a tiny shelf, probably intended for putting plants on, with a very rusty cast-iron fence around it which I worried might not survive me leaning on it. But there was something perfect about the combination of sparseness inside and the view onto a beautiful street outside. It was a place to sleep and from which to explore. That was all I needed.

I had arranged to meet the teacher I’d come to study with the following day. He’d given me his address and I left early to make sure I had plenty of time to find it without being late. The apartment room where we trained was high-ceilinged and spacious. There were students from all over the world, training in a variety of styles. There were several older ladies, two French and one American, studying Tai Chi. Three Danish gentlemen were in one corner doing what looked to me like Chi Gung – energy cultivation exercises for health. Two, young Chinese students, one man, one woman, were training in the circular movements of Bagua. Then on the far side of the room from the door were two young men, one French, one Polish, who were clearly the closest students of the teacher, training in several different arts and doing a lot of the techniques at what looked to me like full power: strikes thudding into limbs and ribs, locks and throws looking painful. They kept going at it though, and no-one batted an eyelid.

It turned out I was to be training with the young bucks. I’d trained enough that I didn’t feel too out of my depth and they went easy on me. They were kind in their own way and the teacher was excellent – light and graceful, but powerful in all his techniques. Quick to spot and correct movements so I didn’t learn or repeat bad habits.

I found a big, beautiful park nearby to eat my lunch and go back over what I’d learnt on my own.

After running through everything several times in the September sunshine, I sat and ate, my black notebook on the grass beside me. Looking at that notebook, I felt empty. I realised I had unwittingly come searching for a new teacher; not just for some intensive week of training, but for the long term. I had come searching for what I’d always unconsciously looked for in a teacher: the ‘Good Parent.’ That archetypal figure, the unconditionally positive role-model and guide for life’s journey. I felt empty because, as good as this teacher was, he wasn’t that. Could never be that. No-one could. That is the gift and tragedy of adulthood: you gain the power to make your life whatever you want it to be, but to grasp it, you have to let go of the child’s dream of the magical saviour who will make everything right for you.

I picked up the notebook from the grass and flicked through the blank pages. I didn’t know what to write in this book, my book. I got to the back and found that hidden pocket and realised I hadn’t looked inside it. There was usually a little booklet about the history of this design of notebook – part of their charm, the association with great creatives and writers for many years. It looked flat and empty this time, the booklet already having found its way to the recycling perhaps, but as I prised the pocket open, something slipped towards the spine where I could get hold of it.

It was a piece of paper, heavy stock like the pages but blue-white in contrast to their rich cream. It was a cheque, made out in my mum’s distinctive, elegant cursive, a cheque for £20,000. I was dumb-struck. This amount of money could completely change my life. I could take a year to just pause, or travel and study with whoever I wanted for a few months (such are the dreams of a learning addict). I should feel happy. Here, surely, was another final symbol of my mother’s love, another little moment of her big-hearted care, and one that would give me the space to heal a little. But siting in the middle of a park in Paris, staring down at the cold white piece of paper, all I felt was empty. Numb.

Sometime later, I don’t know how long, I noticed the sun had retreated and my body was starting to get cold. My eyes refocused on the little slip of paper in my hand, suddenly so valuable, and the golden pages of the notebook in my lap and I felt warm tears start to roll down my face.

I missed my mum.

About the Creator

Francis Briers

By day - facilitator, consultant & coach; by night - word-wizard & storytelling nonsense monster!

I love learning, creativity, books & chocolate. I come here to play & try things out.

More about me here: http://www.francisbriers.com/

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.