Proofreader

An essay on my reflections as a first-generation Nigerian — American child that is heralded as the English expert in the home and thus asked to proofread my mother's writing.

“Chika, can you please proofread this for me?”, my mother asked her in Igbo accent lightened by twenty - seven years of grueling tongue gymnastics performing linguistic feats that could earn her several medals if such a sport existed.

Twenty - seven years and you’re still asking me this question. I rolled my eyes and sigh in protest as if a ten minute cursory glance would severely interrupt my. . . tweeting or whatever social media quotidian activity that occupied me at the moment. At this point I expect her to have a mastery of the English language — it’s the national language of Nigeria for goodness sake.

“Sure, just send it to me. No you don’t have to print it out. Email is fine.” I would suggest Google docs but I don’t want to overcomplicate things. Baby steps.

I perform my usual routine. Speeding through her work, fixing subject verb agreement errors, catching run on sentences, replacing repetitive words with synonyms, and the quizzical correcting of mismatched gendered pronouns. I’ve yet to understand why Nigerian parents often confuse he with she and him with her.

“Nne, What do you think? Is it good? Is my English improving?” She asks in three anxious spurts.

Each time without fail, she poses this question to me, seeking approval from the master of the colonizer’s tongue — her eldest, born and raised in the elusive oyinbo land. The sixth of eight children born to illiterate parents in rural Eastern Nigeria, my mother never imagined that her child would be a bonafide American. She relishes her miracle story and tells it often.

“I was twenty - three, living in Lagos, and working as a secretary for the first lady, Maryam Babaginda. One day, a diplomat saw me and said ‘you have potential. You should be in America.’ Within two weeks, I had a visa and my flight ticket was purchased. So easy! I traveled back to the village to tell your grandmother and grandfather. No one believed me. Me – hmph! No one ever thought that me – small Benedicta -- would come to America. I left everything. Even the man that I was going to marry. God wanted me here [America].”

When I was younger, I didn’t understand the gravity of my mom’s decision and I didn’t understand the qualities that compelled her to eagerly accept the opportunity to leave her familiar life and emigrate to a foreign land.

Where did all that confidence come from? Surely, it couldn’t have just been the unbridled bravado of youth. It takes something magical to decide to change the course of destiny for your own posterity.

She took all that magic and poured it into me.

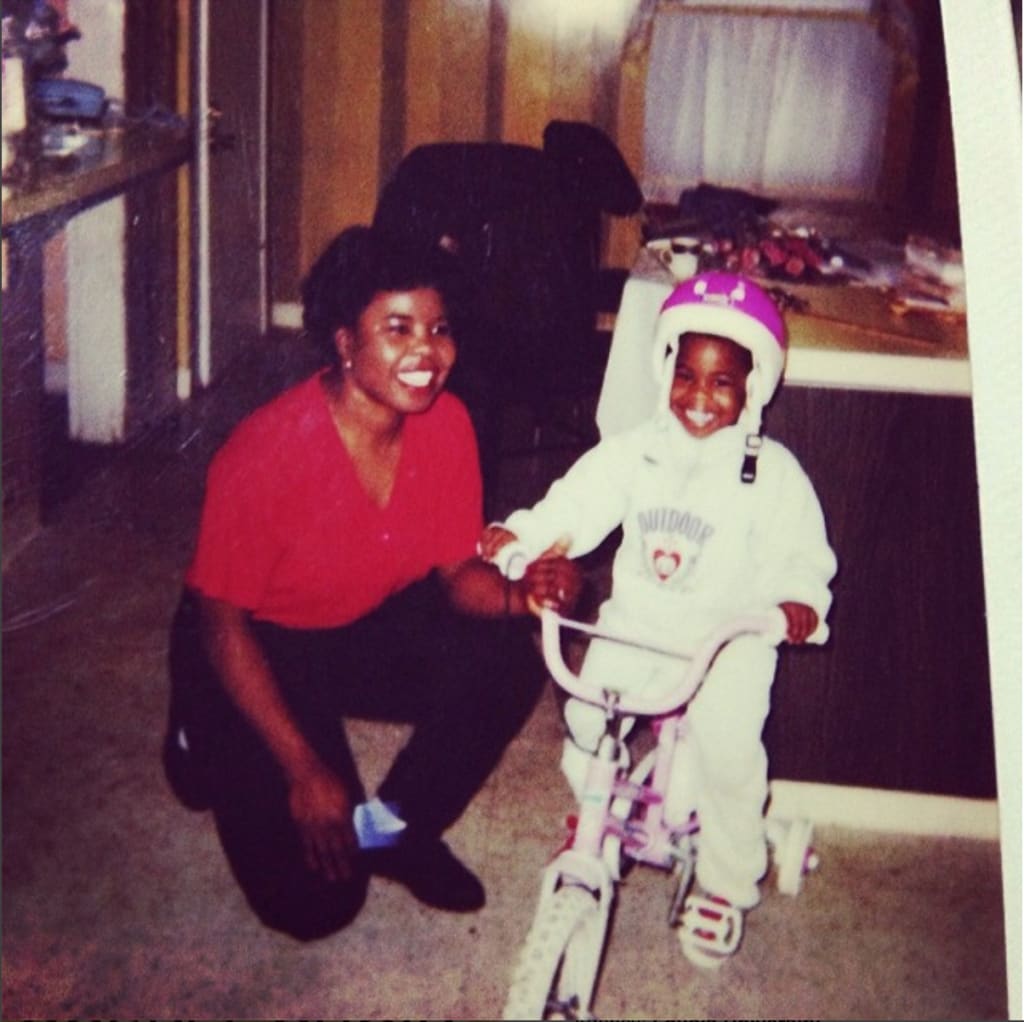

I had her to myself for five years and she doted on me. She started reading books to me at age two. I vividly remember being tucked in the crook of her arm as she narrated the story of Disney’s The Little Mermaid. At age 7, she took me to the Scholastic Book Fair and bought my first chapter book, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Three hundred and something pages was small chops for her American daughter. My preteen summers were spent at the library. She couldn’t afford summer camp. But I didn’t mind. While my peers were swimming on the beach, I was swimming in a sea of books. A sheltered girl, I lived my experiences through characters. My first crush was in Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants. I loved feeling like a badass superhero in Shadow Hunters, and I briefly toyed with the idea of being a Vampire in Twilight Series. It was brief because I couldn’t conceptualize pale brown skin. Eventually, my advanced English classes introduced me to the popular classics, Tess of D’Uberville, A Tale of Two Cities, Wuthering Heights, and the still uncompleted Anna Karenina (thank you Sparknotes.)

My romance with books started with my mom. Ironically, the same woman that introduced the English language to me is seeking my validation.

“It’s fine. Just the usual things that I’m correcting.” I respond.

While proofreading, I’ll often request for her consultation, clarifying the meanings of sentences to make sure she’s writing exactly what she means and means. If I’m irritated, I’ll callously suggest that she should read more, citing the benefits of literature improving vocabulary, grammar, and comprehension skills. I’ll casually make these remarks as if she’s been given the same education as me and exposed to the same content as me. Maybe if the IMF didn’t ask Nigeria to defund their libraries, my comments would be reasonable. And perhaps they still wouldn’t, because who has time to read books as an immigrant trying to find her footing in a foreign land? She was doing enough reading already. Reading the barely comprehensible instructions on how to obtain a visa. Reading the fine print in denied job admissions because they didn’t accept Nigerian school degrees as a viable education background, and reading the expressions of Americans that ridiculed her accent. It’s a miracle that she had time to read to me The Little Mermaid.

I give her writing a final read and return the paper to her .

“Wow, see English. It’s such a blessing to have an intelligent child."

I soberly chuckle. Language has nothing to do with intelligence.

There are millions of people in this country that are often overlooked and ridiculed because of their accents or broken english. Native speakers sometimes treat them with scorn, not realizing that these individuals speak and write fluently in other languages. They are not dumb. They just have not mastered another way of expressing themselves.

“Mom, language has nothing to do with intelligence. And besides you speak two languages fluently while I speak one. What matters is that you’re understood. Isn’t that the goal? So technically, you’re better than me.”

My mom was too busy fighting battles and paving roads for me so that I can read. I have the privilege of dabbling in the more leisurely things of life because of the time extracted from her sweat and given to me.

I smile at look at her. “You have me. I’ll make sure that not a comma is out of place.” I’ll happily proofread.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.