It shouldn't have surprised me when I walked into the house and found Dad asleep in the brown leather recliner I'd bought for him last winter.

I reckoned if he was determined to sleep in a chair, the least I could do was provide him something comfortable. In those last days he barely ate the food I cooked, which had been one of the last things binding us together. By then, we couldn't talk to each other worth a damn. The dementia that rattled his brain and made us strangers robbed him of his appetite. It seemed to bother me more than it did him.

He wasn't asleep. He was dead. It had been a long time coming, but it hit me hard when I walked in and found him that way. He looked just like he always did when he was asleep. But he wasn't asleep. He was gone. I was 46 years-old--a grown man with a wife and a good job and plenty of money in the bank--but I'm not ashamed to admit I cried like a baby.

It took me a few minutes before I could look at him again. He was dressed in the same yellow coveralls he wore most days of his adult life. A green Army blanket was draped over his lap. His head was thrown back, His eyes were closed. I tried to open them with my fingers but they wouldn't stay open.

I don't know what I was expecting.

The chair back was upright. His feet sat square on the floor. Between them was a worn leather satchel like doctors used to carry when they made house calls back in the day, except this one was much bigger. More like a suitcase. Dad's hands lay on the blanket in his lap. In He held in one hand a small, black, leather-bound book. I did not recognize the satchel or the book.

Stuffed inside the satchel were bundles of five-dollar bills, dozens of them, wrapped in those little paper rings the bank uses. On each was stamped "$100." I picked up a bundle up and riffled through it like it was a deck of cards. They weren't like any I'd seen before. Instead of Abe Lincoln, the front had a picture of a fella in an Indian headdress. The writing was bigger and fancier, and of course, instead of Honest Abe, they had a picture of that Native-American fella. I didn't have my reading glasses on me, but I was able to make out a date--1899--and at the bottom the words, "Silver Certificate."

The inside of the satchel smelled like old paper money and my mama's linen closet. I knelt on the floor and dumped the contents onto the carpet. A couple of mothballs and a few dozen stacks of the strange five-dollar bills fell out. It took time to count them. There were exactly four hundred bundles. I've never been good at math, but even I know how to multiply 2 by 1 and add a few zeroes. It comes out to $20,000.

I thought about it as I got up off the floor and called the funeral home. I'd been making plans with them for when dad dies, so they knew what to do. I returned to the living room and sat back down at Dad's feet.

"What is this, Dad?" I said out loud. My eyes came to rest on the little black book. Upon inspection, it seemed at least as old as the satchel. I took it out of his hand, hesitated, then opened it.

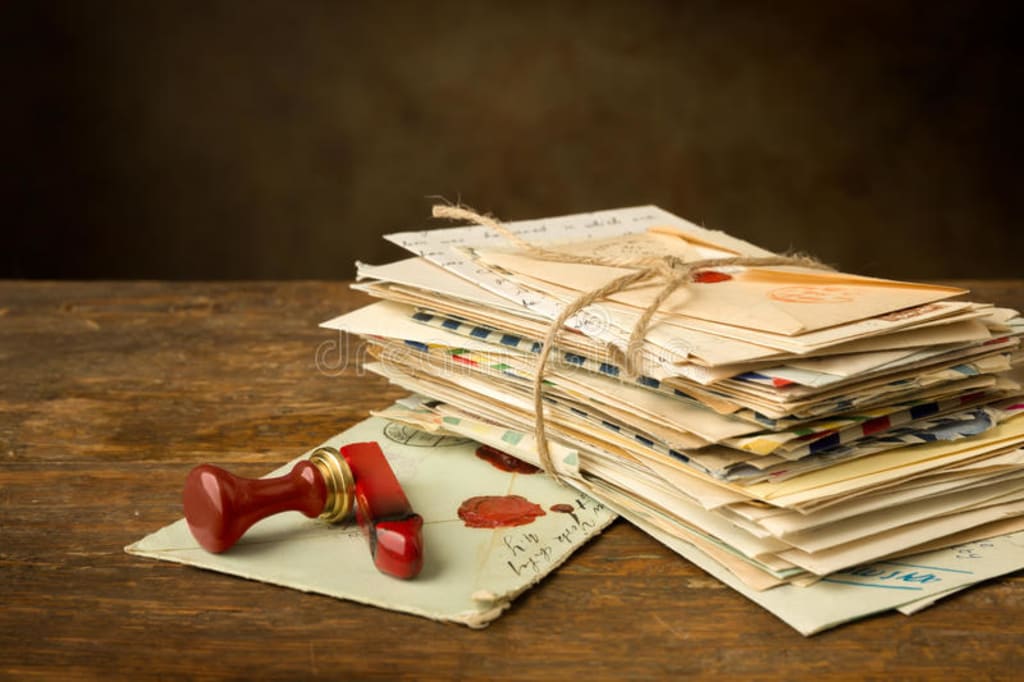

The words "Emmett's Rainy Day Fund" and the date "June 5th, 1927" were written on the inside cover. I'm Emmett. June 5th, 1927 was the day I was born. The small, precise handwriting was my mother's. I recognized it from all the letters she wrote me when I was in the Marines. We didn't get too many mail deliveries, but when we did, there was always a stack from Mama, as thick as the bundles of five-dollar silver certificates now scattered all over the floor.

The book was a ledger. Entered were dates and amounts, along with place-names. The place was usually the small local bank where my folks kept their money, although there were others: "Gift from Aunt Irene in Nashville," or "Piggly Wiggly in Alva." I'd heard of silver certificates before, but I'd never seen any like these. I checked bundle after bundle. They were all the same.

The handwriting changed around 1953--from my mother's clear hand to my father's near illegible scrawl. She died just before I got home from Korea. Dad must've taken over at that point. As the years passed, there were fewer entries. They became progressively harder to read, especially in recent years. I flipped to the back of the book. The last entry was September 11th, 1973. Today was the 12th. He's written in the amount but not where he'd gotten it. I rummaged through the stacks, looking for a loose bill. I couldn't find one.

Later, after the boys from Pate's Funeral Home took Dad away, I folded the blanket that had been on his lap. A piece of paper fluttered to the floor. It was a five-dollar silver certificate like the others, dated 1899.

At the funeral, I told Dad's best friend what I'd found.

He frowned, then smiled. "My Lord, I haven't thought about that in years. Your dad got a stack of those fancy silver certificates down at the bank the day you were born and started socking them away. For years, him and your mama searched high and low for those damn things. I can't imagine the government printed all that many of them. I reckon they probably cornered the market. Your dad always thought they'd be valuable one of these days. You should look into cashing those in. I'll bet they're worth something."

The next day I took the satchel down to the bank. I asked the president what they were worth. He asked if I'd counted them. I said I had.

"How much?" he asked.

"$20,000," I said.

"Then they're worth $20,000," he said and shut his door in my face. A teller who'd worked in the bank as long as I could remember stopped me on the way out. "You know your daddy was just in here a couple of days ago," she said. "He always wanted me to give him a call whenever I came across one of those. I hadn't seen one in years, but I got one earlier this week and called him first thing. He came by and wrote me a check for five dollars and I gave it to him. He saved those for you, did you know that?" I said I did. "He was a fine man, your father."

Later I went down to the library and did some research. Apparently the silver certificates never appreciated in value much. They were still worth five dollars apiece.

I guess Dad didn't know. Or maybe he did and didn't care. What was it about those silver certificates that made him get up out of his chair and drive to the bank the next to last day of his life?

I didn't have to think on it too hard. It made me cry again. I remember thinking I must be getting old.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.