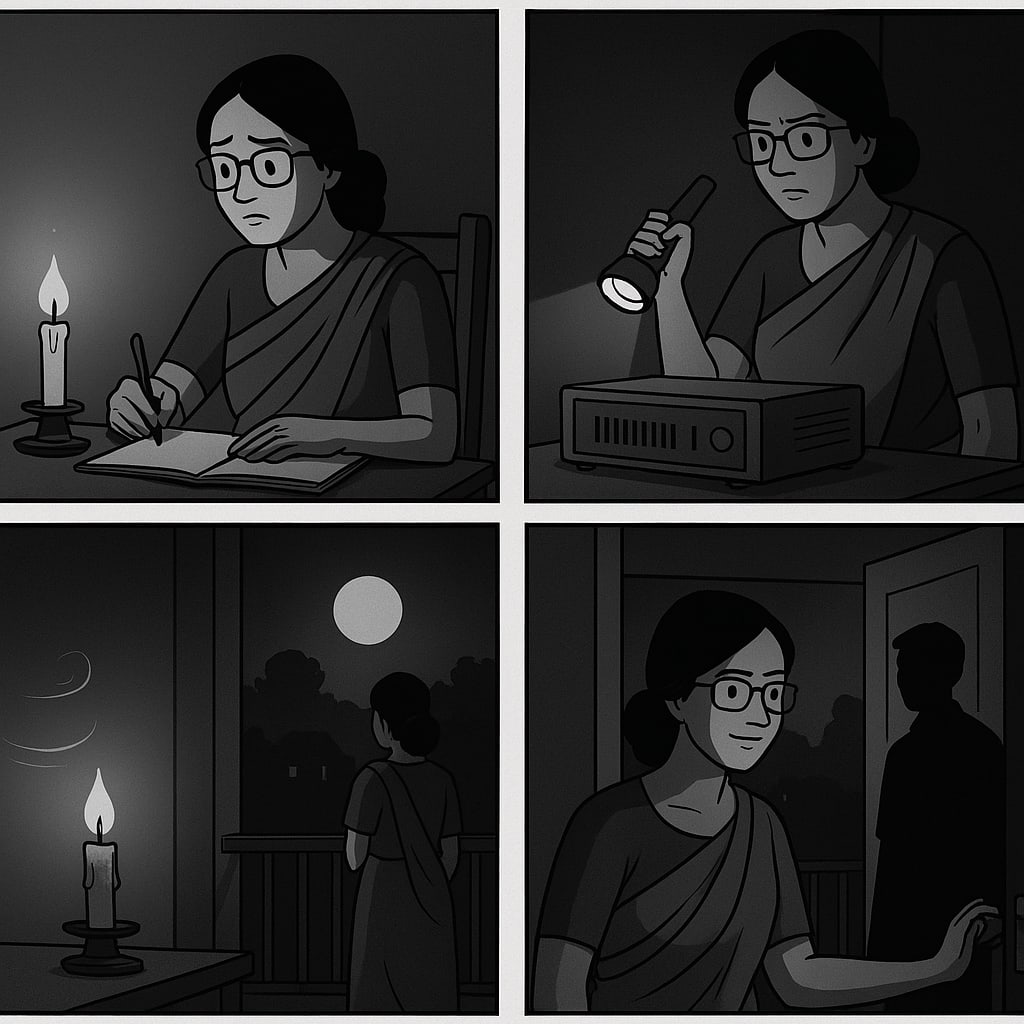

In the sea of imagination, a sudden low tide. The pen darts forward with unstoppable speed and hits a corner of the floor. But the writer can’t see it—she only hears the thud and has to be content with that. The reason? Nothing new—load-shedding. A

h, as ordinary now as boiled potatoes with rice. Just like that's a must on the plate, load-shedding has become a daily staple.

So why did the writer throw her pen away in irritation? It wasn’t baseless frustration. There was reason enough. Load-shedding? Fine. But where on earth did the inverter vanish today? No sign of light. With no choice left, she rises from her chair. But how to move in this pitch-dark room? She gropes around the desk, and after much fumbling, finds her phone. She can tell she’s knocked over the pen stand and other items, whose whereabouts are now a mystery not worth solving in the dark.

She switches on her phone’s torch and walks over to the inverter. But it’s dead silent, like that lizard she found behind the water filter the day before. She doesn’t bother fiddling with the machine—she’s a student of literature, not one to meddle with electronics.

Her husband won’t return for a while—tons of work at the office. A sigh escapes her, born from sheer helplessness. There’s a hurricane lamp in the house, but clearly not functional anymore after all these years. Depending on her phone light, she rummages through the cupboard and finally finds a broken candle. Relief at last.

She lights the candle, breaking it at the bent waist, and sets the top half aflame. Then she pulls a chair and sits down, a thought suddenly striking her—it’s a strange coincidence. The novel she was writing had begun with the exact same kind of load-shedding scene.

The twelve-year-old protagonist of her story wakes up in the middle of the night to find the fan above his head still, the night bulb fused into the darkness. Sweat from his body has already soaked the bed. He realizes that the power has been out for quite some time and even the inverter is dead.

The writer smiles to herself—how true it is, in today’s world, if the inverter fails, we are utterly powerless. She now finds herself in the same place as her young protagonist.

The boy rises from bed and steps onto the balcony, yearning for a breeze. But tonight, the air indoors and out is equally still and heavy. As his eyes slowly adjust to the dark, he sees it—a figure cloaked entirely in black, standing motionless at the gate.. A chill runs down his spine. Who could it be at this hour? A thief?

Curious, the boy leans forward to get a better look. The man looks up—straight into the boy’s eyes. The boy stumbles back in fear. Those eyes weren’t human. They looked like two deep blue fireballs.

“Ah… ah… ah…”

It takes the writer a few seconds to realize her scream was real. Embarrassed, she blushes in the dark. She had been so deep in her story that the glowing eyes of the neighbor’s pet cat startled her. She chuckles nervously, heart still thudding in her chest. A gust of wind suddenly blows out the candle she had so painstakingly lit.

Annoyed, she doesn’t bother relighting it. Instead, she tiptoes to the balcony. The dead moonlight softly drenches her. Something stirs inside her chest. The sweat trickling down her body goes unnoticed.

This is true load-shedding.

The writer’s mind drifts back in time—to when she first moved into this house after her wedding. Everything was new, every step calculated. An inverter was a dream then. If the power went out, she’d never let her husband light the hurricane lamp. She would say, “Enjoy the beauty of darkness—it’s beautiful.” Her husband would grin and reply, “Beautiful my foot! Wait till a ghost grabs you!” Then he would pull her into his arms, and they’d giggle the blackout away.

Twelve years later, what if she made that same request again? Would he smile or get annoyed?

Another memory rushes in—the time she learned she could never be a mother. Every evening back then, she’d sit alone on the rooftop, gazing at the sky, lost in endless thoughts. Not far from her home were slums where people barely found enough to eat, yet had four or five kids. And she—none.

Back then, tears would stream down her face without her even noticing.

But she moved on. She picked up the pen to fill the void. Being a literature student helped. Slowly, she immersed herself in work. That might’ve been the time when the emotional distance between her and her husband began.

She doesn’t go to the rooftop anymore. Or maybe she just doesn’t want to. If she does, she finds only blinding artificial light. It feels like the entire world is watching her. Maybe the darkness of nature has faded, but can light really erase the darkness within?

Lost in thought, her eyes catch sight of a young couple hiding in a shadow nearby. “Oh little rabbits,” she thinks, “you don’t even know—the moonlight tonight won’t keep your secret.”

A memory surfaces. She was in Class Ten—the first spring of her life. Her heart had tasted the colors of love. He was a poet. He loved the dark. He’d often say, “After we marry, we’ll go to the jungle. Sit on a forest bungalow porch, and bathe in moonlight.”

But after school ended, her family sold the village house and moved to the city. There were no cell phones then. She lost all contact with him. Never met again. Even today, when she attends literary events or finds new poetry in magazines, her heart searches for that village poet.

That move from village to city had taken so much from her. So much more than she’d imagined.

She remembers those first eighteen years spent in the village, before electricity had reached. The four siblings would light the hurricane lamp at dusk and study. Afterward, they'd dim the light, snuggle beside their grandmother, and listen to the rhythmic chanting of Ramayana from the next room.

On full moon nights, the shadows of swinging weaver bird nests on palm trees danced in tune with nature’s song. Sometimes Grandma told ghost stories, sometimes moral tales—an entirely different kind of joy.

In summer, they’d sleep on the long verandah of the two-story house. There were no fans, but the breeze through the windows was cooler than any modern machine. Through the iron grills, she’d watch stars and the giant mango tree outside. Sometimes, she’d wake up and think a giant from fairy tales had come to their yard. And on spring nights, the tree was treasured—everyone’s ears alert for the sound of mangoes falling, ready for the early morning hunt.

That was ages ago. A time when both light and darkness were equally cherished.

Now, there’s too much light. Blinding. Perhaps that’s why the writer often finds her eyes dazed, her heart aching.

Someone has been pressing the doorbell nonstop. The urgency in the ring reveals impatience. The writer comes back to reality. Her eyes now adjusted, she no longer needs her phone light. She walks slowly to the door.

She knows the person standing behind it very well.

And she has made up her mind. Once he’s inside, she’ll make that request again. Take a few days off work. Visit a distant relative’s house in that writers’ village—a long pending invitation never fulfilled.

Surely that place hasn’t lost its natural darkness yet.

She’ll ask again—just like she used to.

Let’s see, will he get irritated?

Or, like the old days, will he smile?

The End.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.