When she arrived on our doorstep in 1970, my Great Aunt Sadie didn’t look like a revolutionary, much less a person who would change our lives. She looked exactly like what she was; a supremely huggable church-going mother of seven from Utah; short, bespectacled, and just a little plump. I was 13 to her 70 years, and found her to be nurturing in a way I had seldom encountered. She felt like home; I adored her instantly.

On that first visit though, it was more than her overwhelming warmth that made an impression. It was the mysterious, sheet-wrapped gift she carried in her arms as she walked through the door. We couldn’t tell what it was - it was big and bulky, but clearly not very heavy. With a mischievous grin, she laid it down in a corner, and told us that she’d explain it to us after dinner. She refused to answer any questions, stating merely that my mother had worked hard on dinner, and it was time to go into the kitchen and appreciate it. After eating what seemed like an endless meal, after dessert, and after way too much adult chit chatting, Aunt Sadie announced that it was time. We trooped back into the living room. Aunt Sadie sat my father down in his favorite armchair, and picked up her sheet-wrapped surprise. She carefully took the sheet off, revealing what looked like a bunch of puffy folded fabric. We were puzzled. What the heck? She handed the puffy thing to my father. He took it in his arms and began to unwind it.

It was a quilt.

At first all we could see was the back. It was a pretty floral print; not knowing any better, we all ooohed and aaaahed. Then my father turned it over, revealing colorful round blocks. We were mesmerized. And then, when my father noticed the fabric that made up each block, he burst into tears. As the entire quilt was unfurled and spread across his lap and onto the floor, he began pointing to different fabrics. With tears rolling down his cheeks, he exclaimed “this was one of my mother’s aprons.” “This was Ted’s shirt.” “Ruby loved this dress.” And on and on and on.

This was my introduction to the power and magic of quilts. This was not just a blanket. This was family made manifest, love stitched into fabric, and memories. So many memories

Gilbert, my father, had had more of an Oliver Twist childhood than that of, say, Beaver Cleaver. Georgie, his sweet mother, died in 1938, when he was just ten. And because Gilbert’s father Jesse was “stuck” with a bankrupt farm, a long-distance truck route, and five motherless children, he remarried quickly. He apparently wasn’t very choosy. Verna wasn’t known for her kindness, tenderness nor her compassion. She had very little time or patience for any kids that weren’t her own. In fact, rumor had it that she didn’t much like her own kids, either. Regardless, her three girls ate first; if there were leftovers, the other five were allowed to eat. Verna’s girls took over the bedrooms; the boys were relegated to the dirt-floored basement. And that was just the start. Verna was ornery to the core, just plain mean .

The same year that he lost his mother, who had been both his protector and his champion, he hit his full adult height of 7’. Yes, he was seven feet tall by the time he was ten. In retrospect it was probably a pituitary tumor. But in 1938, in tiny Brigham City, Utah, which had been laid bare by the depression and where a college education was not even the faintest whiff of a dream, no one knew anything about growth hormones and pituitary glands.

Gilbert developed an easy-going attitude and wicked sense of humor to deflect the comments and slights heaped upon him, but that wasn’t enough. When he was 13, he took stock of his life and found it lacking. With his mother gone, his heart broken and his home unbearable, Gilbert and his best friend Johnny Wadman jumped on a freight train to get the heck out of Utah. They were headed for California, where, they’d heard, the weather was always warm, there were orange trees in every yard, and shipyard jobs were going begging. The attack on Pearl Harbor had created an enlistment frenzy; all men over the age of 18 had joined one branch of the service or another. This left just old guys (and, apparently, 13-year olds) to build the warships.

Unfortunately, big ideas often take at least a modicum of planning. The train the boys had flung themselves upon was headed north into snow country instead of south to sunny beaches. They woke up the next morning, shivering in their boxcar, stunned to find themselves in Wyoming. The local cops took pity on them, and after telephoning Jesse to come pick them up, let the boys sleep in one of the jail cells. It was uncomfortable and embarrassing, but warm, and gave them a good story to tell.

They were not deterred. A few weeks later they jumped another freight, this time headed south and west, and soon enough were in Richmond, California. Richmond, however, located right across the bay from San Francisco, was cold, foggy, and didn’t have a single orange tree. The guys they worked with were old, bitter and often drunk. It was rough going. The boys didn’t have money for food; instead they’d skulk into cafes and each order a cup of hot water. When it arrived they’d squirt ketchup into the cup, and add a few crushed soda crackers. After a few days of hard work and fine dining, Johnny Wadman, homesick and cold, headed home. But Gilbert figured just about anything was better than what Verna was dishing out, so he stayed.

There are so many things that I do not know about my father. Many of the details of his early life were told to me by his siblings, since he was reluctant to share the horrors he encountered. I can only imagine what a 13-year-old, wide eyed, seven-foot-tall boy from the sticks was exposed to in that shipyard. Was he safe? Did he ever get enough to eat? Was anyone kind?

I hesitate to say that he grew up; rather, he grew older, became a bit more mature, and in 1956 met my mother at Golden Gate Tip Toppers, a club for tall people. He was Mr. Tall San Francisco at the time. He loved the attention; if people didn’t notice him he would begin to whistle. If that didn’t work, he’d sing. His voice was deep, his laugh contagious. He was an extreme extrovert, enthusiastic about everything, and took delight in the people he met.

On the day she presented the quilt, Aunt Sadie explained that when she came to help out briefly after Georgie died, all those years ago, she had found 16 Dresden Plate quilt blocks stashed among Georgie’s things. In the midst of her grief, and knowing that Verna was hovering on the horizon, she squirreled the blocks away. She wasn’t sure what she’d do, or when, but vowed to keep them safe and eventually get the blocks back to Georgie’s kids. She wasn’t able to stay in Brigham City and help for very long; she had a passel of kids of her own, and a farm to run. But forty years later, with her children launched and “spare” time finally at hand, she pulled the squares out, stitched them together, and hand quilted the whole shebang.

The blocks had been pieced by hand by my grandmother; hours and hours of sitting and stitching. Had Georgie made the squares in the evenings while her babies slept? In the winter while it snowed? While listening to The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet on the radio? Years later Aunt Sadie had carefully sewn them together, added batting and backing, and quilted them, all by hand. I imagine that her thoughts were of her sister, their childhood, their adventures, their relationship. This quilt was love made tangible.

We modern quilters take ourselves off to fabric stores where we buy yards of gorgeous coordinating fabric. We then cut it into little pieces and sew it all back together again. There are myriad patterns available online, along with millions of helpful tutorials, and a flabbergasting array of tools. Most quilters have at least one sewing machine, usually more. Our star points are perfect, seam allowances are all exactly ¼”, and all squares match up, because our tools make it easy. If we do make an irreparable mistake, we usually have a plethora of fabric with which to fix it. Our quilts are a way to express our exuberant creativity, our great big feelings, and to show off just a bit. But in Georgie’s time, quilts, while often beautiful, were ultimately practical. Folks needed bedding to stay warm. There was no such thing as a “Quilt Shop.” When there was money for fabric, it was used to purchase yard goods for a new Sunday dress, or a shirt for a growing boy to replace the one that was now too short in both the waist and the sleeves. The scraps were gathered and sorted and carefully pieced together. Women traded scraps to increase the variety of colors and patterns in their quilts. When clothing was too small and too worn out, the parts that were still usable became quilt squares. All of the sewing was done by hand.

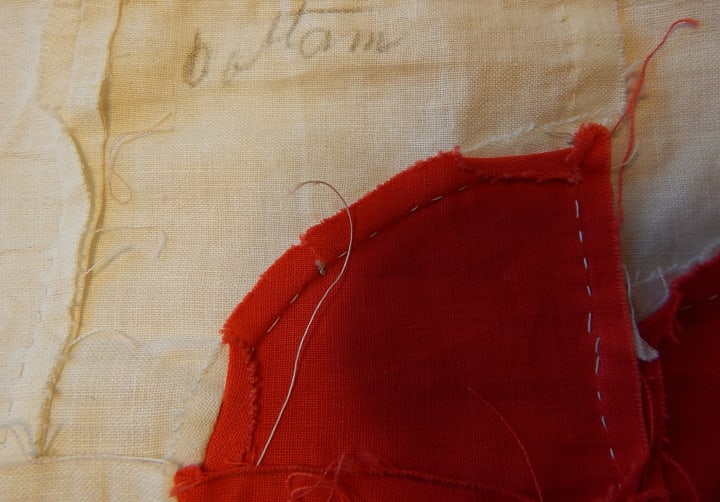

I am now 63. Thanks to the inspirational seed planted by my great aunt Sadie so many years ago, quilting has become a center point in my life. In addition to my own quilting, I have a business where I take forgotten vintage quilt tops and have them hand-quilted by my Amish neighbors. I find these quilt tops at farm auctions and online; all have been stashed in closets or trunks or attics for decades. I have found that quilt making, as well as life, requires determination, a lot of creativity, and often an abundance of help from others. These old quilts remind me of Georgie, piecing quilt blocks from apron scraps, out-grown boys’ shirts, and the less-faded fabric found in the turned-up hems of her daughters’ dresses. They also remind me of Gilbert, taking his less than ideal situation and crafting something bigger and better from it. The vintage quilt tops that I work with were thoughtfully and carefully put together, sewing those small quilt pieces into something bigger, something whole. By completing these unfinished quilts and getting them into the hands of people who will treasure each stitch and square, I feel that I honor the work and the lives of the quilters. When I’m marking the lines for the hand quilting, or choosing the ideal fabric for the binding, I am always thinking of the women who came before me, including my grandmother.

When I first began quilting I had a pair of Gingher scissors, a gift from my mother. Like all seamstresses, we hollered at anyone who dared to use our scissors on anything but fabric. As I began to do more hand quilting, I switched to Fiskars, as they are lighter weight, easier on my hands, and still quite sharp. While I still reserve them exclusively for fabric, I am less adamant about their use. I have nine or so pairs; at any given time I can usually find at least three. I often think about the ease with which I can do my work, the quality of my tools, and how readily accessible they are. How different my life is from my grandmother's, and yet, how much the same.

I never got to meet my grandmother Georgie. But the quilt she started and my Aunt Sadie finished is on my bed. It’s rather tattered now - there are places where the fabric has worn and torn, and the spot where someone had a broken ball point pen in their pocket. But that’s okay with me. When it’s time, I’ll pass our family quilt down to my nieces, along with all of my half-finished quilts, scraps of favorite fabric, and tools, including scissors. I’ll tell them stories about Georgie, their great grandmother, and Gilbert, their grandfather. Then they, too, will understand that quilts are all about family, and love, and are much, much more than a blanket.

About the Creator

Alline Anderson

Displaced Californian living at Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage. I dream of France. And Newfoundland. Collage. Dogs. Books. Cakes. Quilts, old & new. She/Her

Insta @MsMilkweed

www.amishquiltingbyhand.com

https://www.etsy.com/shop/MrsMilkweedsJam

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.