Wrong Verdict Left A Superpower 400 Years Back

The Real Story; Where Fear Ruled the Faith

History remembers empires not just for their armies and architecture, but for their ideas. The Ottoman Empire once stood as the world’s most powerful Muslim civilization — stretching across three continents, ruling millions, and shining as the center of Islamic art, science, and faith. But one fateful decision, a verdict given by its religious scholars, would change the course of history and cost the Muslim world four centuries of progress.

It was the ban on the printing press, the moment when fear triumphed over curiosity, and tradition stood in the way of innovation.

A New Invention Meets an Ancient Power

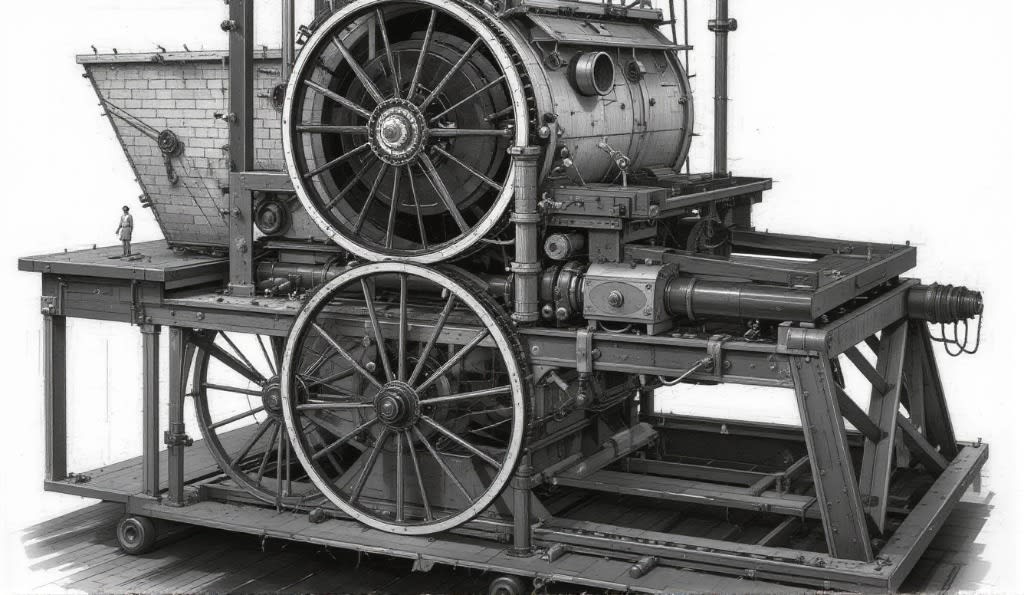

When Johannes Gutenberg unveiled the printing press in mid-15th-century Europe, it changed everything. Knowledge, once confined to the handwritten manuscripts of monks and scholars, became accessible to the masses. Books multiplied. Education spread. New ideas flourished. Within decades, Europe entered the Renaissance and Reformation, leading to a scientific revolution that transformed the world.

At that very moment, another world power; the Ottoman Empire; was at its height. The Muslims ruled from Istanbul to Mecca, Cairo to Belgrade. Their libraries were filled with knowledge, their calligraphers renowned for their beauty, and their scholars respected across continents. But when the printing press reached Ottoman shores, it was not welcomed as a gift of knowledge. It was met with suspicion, even hostility.

The Fatwa that Froze Progress

In the late 1400s, during the reigns of Sultans Bayezid II and Selim I, Islamic scholars (علماء) issued fatwas declaring the use of the printing press to print Arabic or religious texts as haram; forbidden in Islam. Why would scholars, the guardians of knowledge, oppose an invention that multiplied books and preserved ideas?

The reasons were complex, not simply a rejection of progress. Printing sacred texts like the Qur’an using ink and metal plates seemed to them disrespectful. Early printing technology lacked precision, and any small error in the Qur’an or Hadith could lead to grave sin. Moreover, printing lacked the artistic soul of calligraphy, an Islamic art form deeply tied to spirituality. Thousands of calligraphers, scribes, and copyists depended on manual book production for their livelihood. Scholars feared the machine would destroy a sacred craft and the economy that supported it.

For these reasons, the Ottoman rulers chose caution over innovation. The printing press was banned for Muslims, while non-Muslim minorities — Jews, Greeks, and Armenians — were allowed to print books in their own languages.

Three Centuries of Silence

While Europe printed millions of books, the Muslim world continued to rely on handwritten manuscripts. Knowledge moved slowly, confined to elite scholars and royal libraries. Education remained exclusive. Scientific discovery stagnated.

The ban didn’t just prevent the printing of religious texts — it delayed printing of all Arabic-script books. Between 1485 and 1720, the Islamic world missed the single most powerful revolution in human learning.

Meanwhile, in Europe, printed books spread new scientific theories, philosophies, and political ideas. Universities expanded. The Industrial Age began to take shape. The world was moving forward, while the Muslim world — once the torchbearer of global science and civilization — was falling behind, not because of invasion or poverty, but because of a wrong verdict.

The Reversal: When Wisdom Finally Awoke

In the early 18th century, a remarkable man appeared: İbrahim Müteferrika, a Hungarian-born diplomat who had converted to Islam and served in the Ottoman court. He believed that the decline of the empire was due not to the lack of faith, but to the lack of knowledge. Müteferrika argued passionately that printing was not against Islam — it was, in fact, a tool to preserve and spread it.

In 1727, Sultan Ahmed III and the Grand Vizier Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha gave their permission for the first Muslim printing press in Ottoman history. Müteferrika even obtained a fatwa from the Shaykh al-Islam, the highest religious authority, declaring it lawful to print books on science, geography, and history — though printing the Qur’an remained restricted for some decades more.

At last, the Ottoman Empire entered the printing age. Müteferrika printed works like Tarih-i Naima (The History of Naima), Cihannüma (The Atlas of the World), and dictionaries. His press produced seventeen books in fourteen years — a slow start, but a symbolic rebirth.

Too Late to Catch Up

By the time the Ottomans reversed the ban, Europe had already printed millions of books. The difference in literacy, education, and scientific progress had grown into a gulf.

Europe had universities filled with printed textbooks, while Muslim students still copied lessons by hand. Europe had newspapers spreading new ideas daily, while Muslim societies relied on word of mouth and sermons.

The result was not just educational backwardness — it was civilizational regression. The wrong verdict, given centuries earlier out of fear of disrespect, had silently crippled the very civilization that once built the world’s greatest libraries and universities.

Printing Becomes a Blessing

By the 19th century, the Islamic world began to fully embrace printing. Religious scholars, particularly from Al-Azhar University in Egypt, declared that printing the Qur’an was permissible as long as strict proofreading ensured accuracy and respect.

Soon, printing presses flourished in Cairo, Istanbul, Delhi, and Tehran. Newspapers, journals, and books revived public thought. Modern education spread. The ban that once silenced the Ummah now gave way to an era of rediscovery.

The Lesson: Fear Should Never Rule Faith

The tragedy of the Ottoman printing ban isn’t simply about a machine. It’s a reminder of how fear of innovation can paralyze a civilization. Islam itself never forbade knowledge or technology — in fact, the Qur’an repeatedly commands believers to read, learn, and reflect. The error lay not in the religion, but in the interpretation.

That “wrong verdict” born from misunderstanding, fear, and over-caution left one of history’s greatest superpowers 400 years behind its rivals. It took centuries for Muslim scholars to recognize that the printing press, far from being haram, was a divine blessing when used wisely.

A Final Reflection

The world today faces new inventions — artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, digital economies — and similar debates about their morality and impact. The lesson from the Ottoman era is clear:

When faith and intellect work together, civilization rises. When fear and rigidity take over, it falls. The wrong verdict on the printing press is a story not just of the past — it’s a timeless warning. Because progress doesn’t wait for anyone. And when a nation chooses hesitation over knowledge, the world moves on without it.

About the Creator

Keramatullah Wardak

I write practical, science-backed content on health, productivity, and self-improvement. Passionate about helping you eat smarter, think clearer, and live better—one article at a time.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.