Why Astronauts Lose Up to One Liter of Fluid per Day in Orbit — And What It Means for the Future of Space Travel

Space

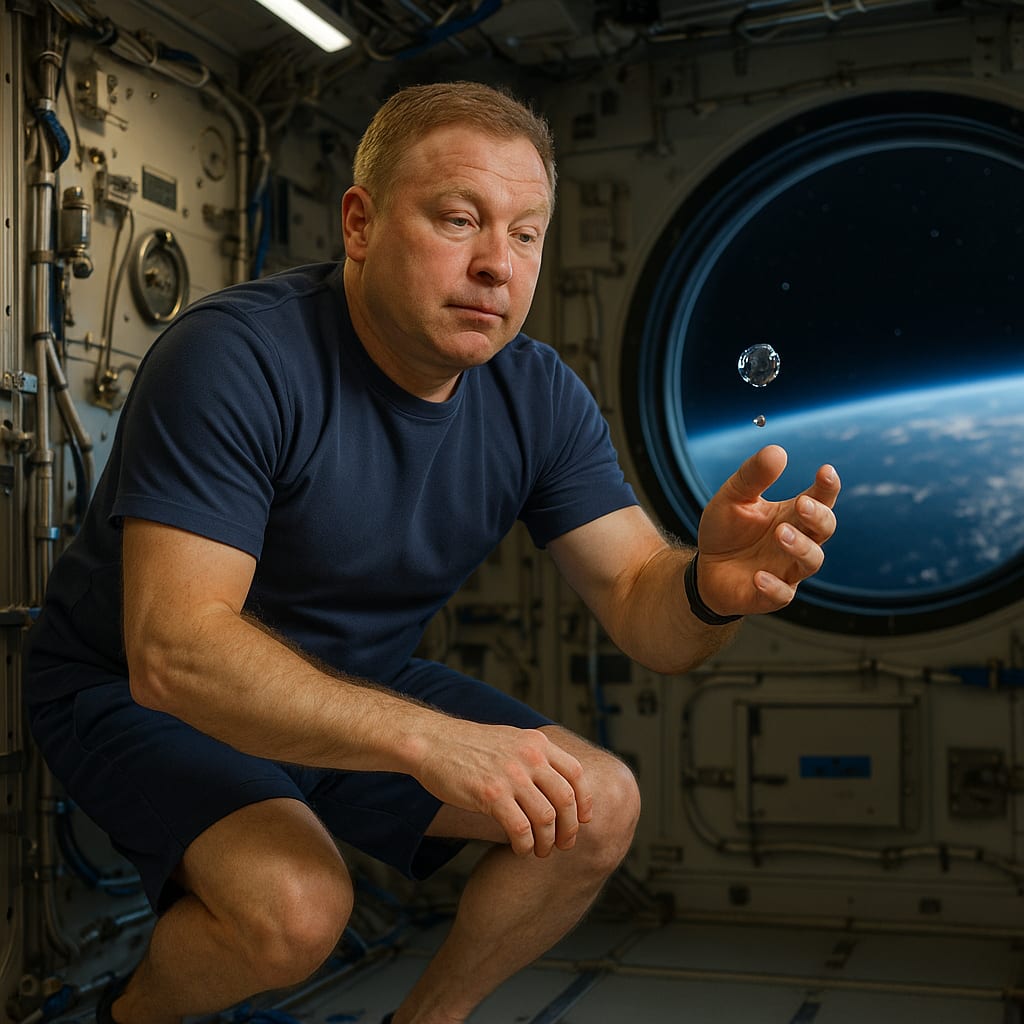

When humans leave Earth, they don’t just float — their bodies fundamentally change. Bones weaken, muscles shrink, vision shifts, tastes change… but one of the most dramatic transformations happens almost immediately: astronauts start losing up to one liter of bodily fluid per day. Not because they sweat more or because the spacecraft is too dry, but because microgravity tricks the body into believing it has too much liquid.

This fluid shift is one of the most fascinating — and surprising — effects of living in space. And understanding it isn’t just scientific curiosity; it’s crucial for planning long-term missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

What Microgravity Does to the Human Body

On Earth, gravity pulls fluids downward. At any moment, more blood is naturally pooled in your legs and abdomen than in your chest or head. Your cardiovascular system works constantly to overcome this pull, ensuring your brain gets enough oxygen.

But when gravity disappears, so does that downward pull.

The result?

- Fluids move upward.

- Blood volume increases in the upper body.

- Astronauts’ faces puff up.

- Their legs almost immediately look thinner — a phenomenon astronauts jokingly call “bird legs.”

Imagine doing a handstand for several hours. Your head would feel full, your face swollen, and your nose stuffy. Now imagine feeling like that 24/7. This is essentially what microgravity does.

Why Astronauts “Lose” a Liter of Fluid

Once fluids shift toward the chest and head, the body interprets this as fluid overload. Special pressure sensors — baroreceptors — located in the neck and heart detect that the upper body suddenly has more blood than usual. They assume the body has simply too much fluid overall.

And the body responds in its typical, brutally efficient way:

- It reduces the release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), which normally helps the body retain water.

- It increases urine production, flushing out what it perceives as excess liquid.

- It reduces plasma volume, thinning the blood to a level that feels “normal” in weightlessness.

Within just a day or two, astronauts can lose up to a full liter of fluid. It’s like the body hits a “reset” button—but one designed for Earth, not space.

What This Fluid Loss Feels Like

Astronauts often describe the first few days with a mixture of discomfort and wonder.

- “Space Head” — a pressure-filled sensation in the skull

- Constant nasal congestion — many crew members say it feels like having a cold

- More frequent trips to the bathroom

- A noticeably tight helmet or headset due to facial swelling

Astronaut Chris Hadfield once joked that when you first enter orbit, you look like “you’ve been hanging upside down for a week.” And according to many astronauts, food tastes blander until the body adapts—partly because of sinus pressure and fluid congestion.

The Hidden Dangers After Returning to Earth

The real trouble begins when astronauts return home.

After weeks or months in microgravity, their bodies have become accustomed to a reduced blood volume. But back on Earth, gravity returns instantly. Blood rushes downward into the legs again, just as the cardiovascular system realizes it no longer has enough volume to keep blood pressure steady.

This mismatch can lead to:

- 1. Orthostatic Intolerance

This is a fancy term for “I stood up and nearly fainted.” Many astronauts experience dizziness, weakness, or blackouts when trying to stand in the first hours or days after landing.

- 2. Heart Strain

The heart has to suddenly pump harder again, but the reduced plasma volume and weaker cardiac muscle make that a challenge.

- 3. Reduced Exercise Tolerance

Simple tasks—walking, standing, bending over—take effort. Even highly trained astronauts often need assistance exiting the capsule after landing.

How Space Agencies Counteract Fluid Loss

To prevent severe problems during re-entry, astronauts follow strict countermeasures:

● Hyperhydration Protocols

Before returning to Earth, astronauts drink special electrolyte-rich beverages to rebuild blood plasma levels.

● Compression Garments

The Russian Chibis suit, for example, creates negative pressure around the lower body, pulling blood back toward the legs — essentially simulating gravity from the waist down.

● Customized Exercise Regimens

Daily workouts on treadmills, resistance machines, and stationary cycles slow the degradation of the cardiovascular system.

These strategies don’t eliminate the effects but make them manageable.

Why This Matters for Deep-Space Missions

On the International Space Station, astronauts can return to Earth within hours if needed. But future crews traveling to the Moon, Mars, or long-duration stations will face much higher risks. Some missions may require:

- 6 months of travel to Mars

- Over a year spent in reduced gravity

- High-G landings or emergency maneuvers that demand a strong cardiovascular system

If astronauts lose too much fluid or can’t regulate circulation on landing day, the consequences could be dangerous — or mission-threatening.

This is why NASA, ESA, SpaceX, and other agencies are studying fluid shifts intensively. Understanding them is key to keeping astronauts healthy on journeys far beyond Earth’s orbit.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.