The Structure behind the Free Word Order of Ancient Greek

Why & how ancient Greek allows such freedom, and how tree diagrams explain it

If you, like me, have recently started learning Greek, you might have heard that it has a free word order. That might either make you happy that there are no rules to learn or confused about how they even understood each other then.

Turns out, there are rules behind that freedom, and thinking in structures and diagrams can help you make sense of them.

In this article, we'll be tackling the topic of the free word order of ancient Greek, asking

- whether words with a certain role have a home in the sentence structure;

- what mechanisms move them around;

- and how do draw a sentence like that as a tree diagram.

The Framework We'll Use for Sentence Structure

When starting to learn a language, I create a mental map of its sound and sentence structure - not just out of curiosity but so that I could make better sense of the sentences and grammar I would encounter on my way.

What makes this plunge into the unknown easier is that I don't start from a blank slate. Instead, I use the X-bar theory, which posits that every phrase in every language has the same underlying structure:

If you're new to the system, I recommend reading this article first: How to Use the X-Bar Theory to Make Learning Grammar a Piece of Cake. However, I will try to give you the basics you need in this article, too, to give you the tools to make sense of ancient Greek's so-called free word order in a way that traditional grammar explanations often fail to do (and the linguistic ones are too complex and detailed).

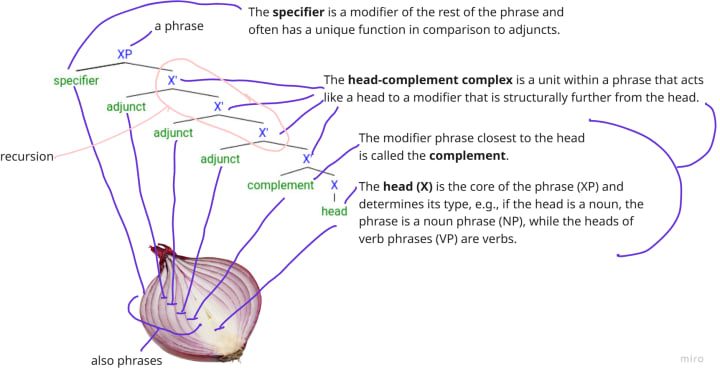

The main idea is that a sentence is not just a string of words with some sort of magical relationship between them but rather a structure. Kind of like a bulb, as in, words are grouped into phrases within phrases, with additional information growing like layers around a core. In syntax, we call the onion a phrase, while the core of the bulb is the head, which the layers modify.

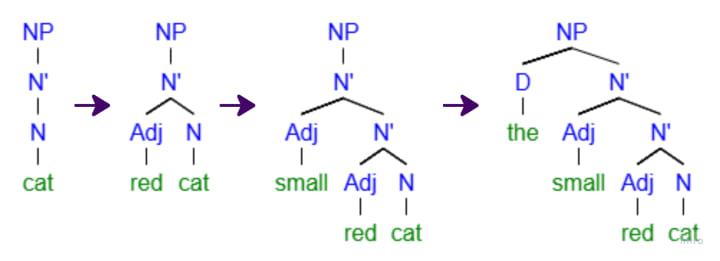

Let's see an example. I'm going to take noun like "cat" and elect it as the head of our phrase. That makes it a single-word noun phrase, NP for short.

I can now add a modifier, which for nouns is quite often an adjective (Adj), so let's say that we have a "red cat", because why not. We can modify the construction we have now, clarifying that the red cat is a "small red cat". Here, the adjective "small" is added to not just the cat but the whole concept of a red cat. Not a large red cat but a small one. Now, "red", the modifier closest to the head is called a complement, while additional modifiers, like "small" are called adjuncts. To account for this structure within a structure, the X-bar theory proposes a structure between the head (X) and the phrase (XP), the, well, X-bar, which is supposed to be an X with a bar over it, which is hard to type, so I (and many others) use X' instead. Depending on the phrase, you might have a string of X's one under another.

Finally, since we're speaking English, we usually need an article, too: "a small red cat" or "the small red cat". Actually, it isn't always even an article - it could be a demonstrative pronoun, too, like "that red cat". Both articles and demonstratives make up a class called determiners (D), and you might notice that in English, they always come first in a noun phrase. You're not gonna say that you saw "small a red cat" or "small red cat a". You're not gonna use two determiners together either, as in "that the small red cat", are you? This is why tree diagrams in the X-bar theory have a special slot called the specifier, which is a sibling to (beside) X' but not a child to (under) it.

Some final things to note. (1) Each modifier is actually the head of their own phrase, so we could expand the AdjP "small" to "very small" (adding an adverb). (2) We always divide each layer into two at max. No parent in this realm has 3+ kids, and the eldest kid, who always happens to be most like their single parent, rules over their only sibling, if they happen to have one.

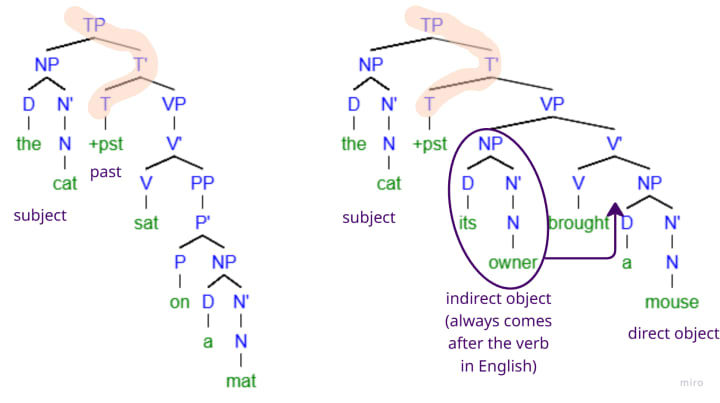

So how do we build a clause?

My introductory article explains more about why you need it that way, but in a simplified X-bar system, a clause is a tense phrase (TP). The head of such a phrase, is, of course, tense, which is, yes, an abstract property, not a part of speech, like the rest of the phrases. Its specifier is (usually) a NP - the subject of the sentence. The complement, on the other hand, is the predicate verb phrase (VP).

The verb phrase can have its own arguments (calling them modifiers does not always seem as right as it does for nouns), and in the context of ancient Greek, it's important to note the position of NPs within the VP: the complement NP of a transitive (=can have complement NPs) predicate verb is the object of the sentence, and a NP occupying the other important position, the specifier, acts as the indirect object of the sentence.

Great! Now that you've got the basics, we can jump into the peculiarities of ancient Greek.

What does it mean that ancient Greek has a free word order?

Descriptions of ancient Greek, like this one you're reading, often state that the word order of ancient Greek is free. That is true to an extent. Yes, there are many optional word orders for the same sentence. No, you can't just put words in a box, shake it, and then blindly pick one after another. The resulting order still fits into the same overall tree structure: it's just that the branches are more flexible and can be arranged to create the composition you like. Maybe variability, then, is a better word for describing the ancient Greek structure than freedom.

And it's not like it was done willy-nilly. Along with intonation, deviations from the more neutral order were used for emphasis. Words were arranged to fit the context of the conversation, for example, by putting the stuff your conversation partner knows first and presenting the news after they know what you're talking about.

Before we get into the mechanics, we need to understand

WHY could ancient Greek have a relatively free word order?

The reason is that ancient Greek morphology is more complex than that of, say, English. Ancient Greeks inflected their words, using different forms of the same word depending on its role in a sentence. More specifically, ancient Greeks conjugated their verbs by the person and number of the subject and aspect + mood + tense and declined their nouns based on the slot they occupied in the sentence structure.

By the way, modern Greeks do the same. Their system, though, might be simpler, but I'm not entirely sure, and that's not our focus today.

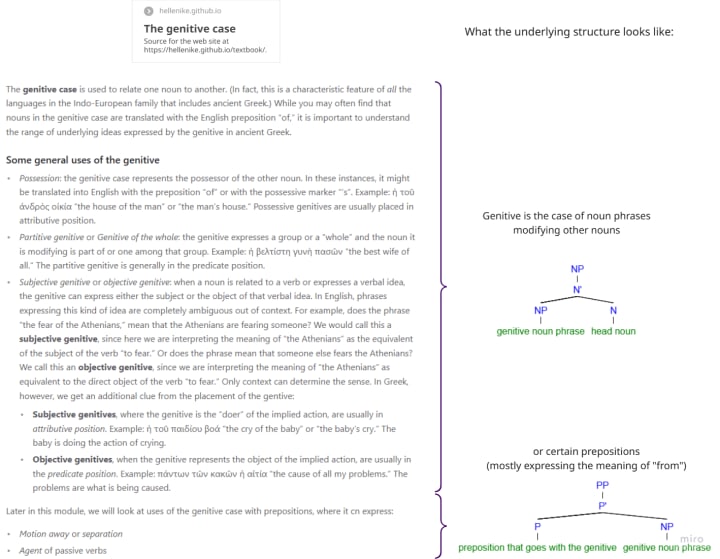

Traditional grammars often explain noun cases (forms of declension) based on their contribution to meaning. That's nice and all but not the best way to define a case. Besides, for all the usefulness of detailed descriptions, the real key to learning is the skill to reduce them to a single picture in your mind. Here's an example of how tree diagrams make it easier to understand grammar - in this case, the use of the genitive case in ancient Greek.

Not that the description on the left is useless - it gives you the broader context and details on the usage (that we can use to analyze the structures!), but as time goes, you forget all those lists of occasions where something is or isn't used. What you remember is the overall idea, and the goal of structures is to give a principle, a picture that you can apply to any of the situations that a traditional grammar description might list, because deep down, they're all just different sides of the same thing.

That underlying characteristic is what actually makes the rule: the genitive, for example, is not the case for expressing possession, groups, or subjects or objects in weird places, even if in this particular language, it is used in those situations. The actual definition of genitive is based on sentence structure, and meaning & usage emerge from that.

Ok, so why would people go through the extra pain of declining their nouns and conjugating their verbs? The reason, as for many weird language quirks, is clarity. The different forms act like a tag on the word that shows what it does in the sentence, so you don't have to worry about moving it around as you feel for artistic purposes like emphasis and flow of logic. (Speech counts as an art, right? It definitely takes effort and practice to speak masterfully and with style XD)

As for nouns, ancient Greek has the following cases:

- nominative – basic form of the noun, also the subject (specifier of TP);

- genitive – NP within another NP;

- dative – indirect object (specifier of the verb phrase, VP);

- accusative – direct object (complement of the VP);

- and one that's more of an addition to the structure, rather than a clear slot – vocative, which is used when addressing someone.

This means that if you put a noun in a weird place (or even something modifying it, since modifiers of nouns agree with their head nouns in terms of case and number), you will still know what it does, which gives you the freedom from a set word order like that of English, where if put you out of order the words, weird sounds it if that can you even understand.

Alright, now we know why ancient Greek order is variable, but

How does ancient Greek move words around?

And what are the rules behind the changes? Because "the cat sat on the mat" is not the same as "the mat cat sat the on". No offense to that poor string of words but the latter sounds bonkers, even assuming English had case suffixes.

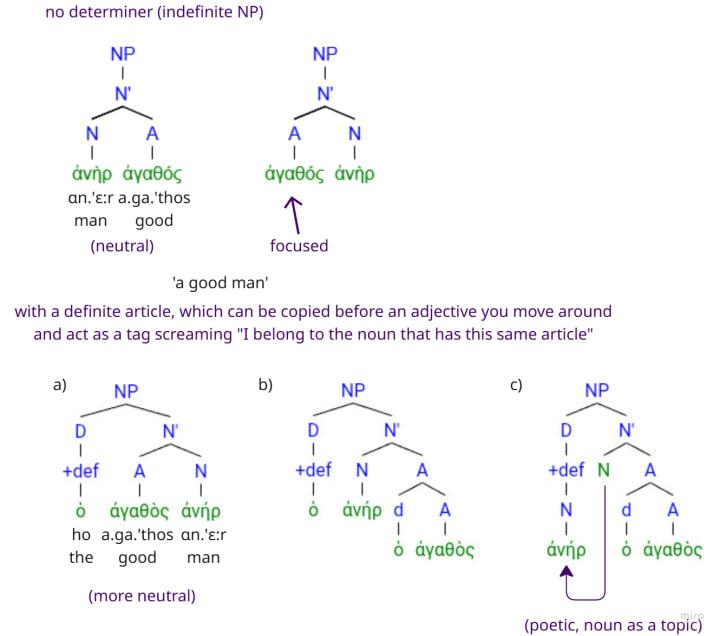

The way I analyze the structure from an X-bar theory-based perspective, ancient Greek has two mechanisms for changing the word order. Generally (though not always), you can emphasize a phrase by moving it to an earlier position in the parent phrase or sentence. The emphasized phrase can move both within the parent phrase and outside of it.

Mechanism #1: Within the constraints of a phrase, you can reverse the head-complement directionality.

The head-complement directionality is just a way to express the preferred location of the head of the phrase: whether the head prefers to be on the left side in the tree (head-initial) or on the right one (head-final). There are whole languages that are strictly head-final or head-initial and others where it depends on the phrase (though there might be a general tendency), and yet others, like ancient Greek, where a phrase has a certain... preference (I sure have a strong preference for that word right now), a neutral position, which we can mess with by turning the phrase upside down or, well, left to the right or first last, or something. Here are some examples.

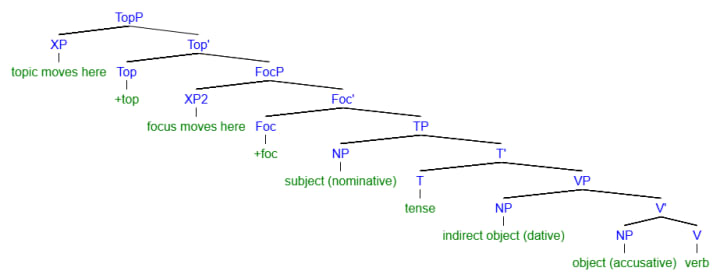

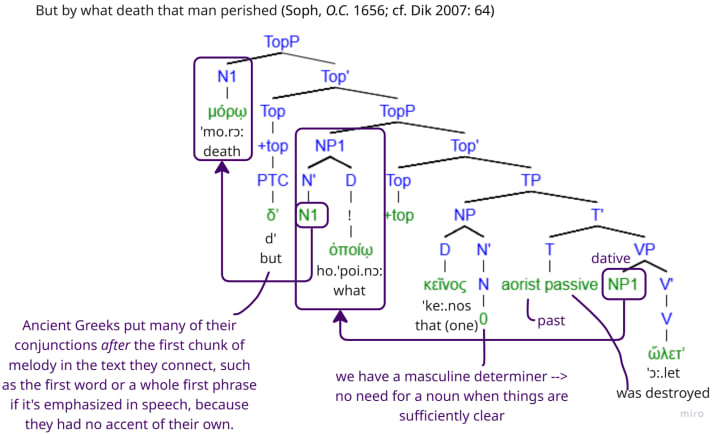

Mechanism #2: Ancient Greek sentence trees have special phrases that allow movement outside parent phrases.

(Is that, like, a college dorm or something?)

As I mentioned before, speakers of languages with "free word orders" have a clear (mostly, of course, subconscious) reason for why they mess with the word order. The order emerges from a mix of strategy & drama, arranging words in a way that fits the logical & emotional flow of the text so that ideally,

- it's clear what you're talking about (state the topic and share background information first, both in relation to the previous sentences and within the same sentence),

- the new / shocking information comes in a place where it is recognized as such (the focus position).

Within the X-bar theory, you can account for that with functional phrases like the topic phrase (TopP) and the focus phrase (FocP), located above the tense phrase (TP). The topicalized or focused information moves to the specifier position of TopP or FocP accordingly, and the rest of the sentence lives in the complement position of these higher phrases. Usually, the verb follows the focus of the sentence, taking its residence at the position of Foc=+foc (meaning, focus exists - the opposite to -foc, which means that there's no focus, although admittedly, why draw such a phrase then).

Here's a rough diagram of the overall sentence structure:

And here's an example sentence with a double topic:

This second mechanism, by the way, is very similar to the one I found while looking into the sentence structure of Hungarian, so this pattern works across languages.

I hope this has sparked your curiosity about the structure of ancient Greek!

You should now know the basic structure you need to draw tree structures of simple ancient Greek sentences (especially if you get confident with the framework itself), so go experiment with it! If you do, you can hop inside the Beyond the Rules Language Learning Discord server and ask me to have a look.

If you wish to go deeper into the sentence structure of ancient Greek, whether as a learner or just a dabbler curious about the language, you can apply for 1:1 online tutoring for 15Eur/hr, where we establish clear foundations of the X-bar theory framework (if necessary) and decode the structure behind word order rules and syntax-related quirks of ancient Greek. As an alternative, if you prefer to explore at your own pace, you might be interested in my deep-dive PDF lesson on ancient Greek noun phrases.

And if you'd rather decode the sentence structure of another language, whether to transform complex word order rules into a single tree structure or just out of curiosity or love for seeing the logic behind Language, we can arrange that, too, no matter your target language (as long as there's enough info available on it on the Internet :-)).

To the pursuit of our language curiosity! 🥂

PS. Since we mentioned the server before, I'm seriously playing with the idea of organizing language exploration months or more likely roughly bi-monthly projects where we dive into the sound, structure, and, of course, real, native-made content, of a language new to us. I've realized that at the heart of many of those language lovers who constantly battle the temptation to pick up yet another language is made up of two aspects: one of them is the ambition to reach proficiency in many languages, yes, but the second one, curiosity, the desire to explore ever the next language and its strange features, is often even stronger. The Beyond the Rules Language Learning server aims to honor both parts. If you want to make language exploration a purposeful part of your life, join in and vote for the language!

About the Creator

Jūlija B.

Hey, I'm a multipassionate med student self-studying languages & linguistics and a math tutor trying to find time for music and writing, which I use as an excuse to explore anything that captivates my heart. https://buymeacoffee.com/julijab

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.