How to Learn the German Word Order Using the X-Bar Structure

Hint: forget "order"

Learning the sentence structure of your new target language first is truly a good idea. It gives you a cohesive framework for the rest of the language's grammar, and, once you upload it to your head, it becomes way easier to understand new sentences, since you know when to expect what kind of information, and to generate your own. Solid knowledge of the sentence structure of your target language functions like a net you can use to catch vocabulary during the fun immersion activities.

That's what I decided to do for German. I found an exhaustive article listing countless rules on where to put each type of each class of words in which situation, each rule with a couple "exceptions" and a combination mix of "this word messes with the usual order while this one doesn't" and "it's more of an art than a science" for something that was indeed simple science.

Because I had the right tool.

I approached this grammar topic with the goal of not just learning the German sentence structure but also practicing applying this interesting framework I'd read about in my introductory linguistics book. And, as I tried it out, I realized that all the complexity of the rules and all the exceptions and nuances can actually be explained by the very same thing in every situation.

Before we jump right in, though, I want to point out that if you're asking how to learn the word order, there are various approaches. You could also stop worrying about it and just focus on consuming content in German and absorbing the sentence structure subconsciously. That's certainly a valid way to go about it, and the one that works for those who become natives. However, if you're here, you're probably looking for an explanation that would help you understand the German word order consciously, so I'm going to try my best to teach you the tool that distilled all the bizarre and complex “if this, then that” kind of rules into one super easy framework.

A Maximally Brief Introduction to the Framework

The tool I want to share is generative grammar, more specifically the X-bar theory, which is a system for the visual representation of the structure of any phrase in any language. Notice that I've used the word structure, not order, several times throughout the article already because languages express meaning through structure, so trying to understand them linearly is just not going to work.

It may help to first read this article to gain a better foundation of the system: How to Use the X-Bar Theory to Make Learning Grammar a Piece of Cake. Not everyone has the time, energy, and desire for a deep dive into theory, though, so let’s start with a simple noun phrase and build it up from there.

Every noun phrase has a noun head. Let's take the noun king, or König in German. Right now, we have a noun phrase that looks like the tree structure below where N represents the noun head and NP represents the whole noun phrase.

Now, we can expand the phrase by adding a modifier, such as the adjective new, or neu. In German, when we place the adjective in the NP, it takes on the marker -e, plus it has to agree with the noun in gender, in this case taking on the masculine suffix -r, which yields the phrase neuer König. This kind of modifier is called a complement, and each modifier we add is actually a phrase in its own right, even if it's composed of a single head. For now, we can visualize it as

Just like English, German does not stay there. In most situations, NPs require a determiner, like a, the, or this, which translate to ein, der, and dieser accordingly, with the gender matching the head of the NP they've been placed in. Once you attempt to put these in the structure, you might notice several things.

- A determiner doesn't fit anywhere else but at the beginning of the NP, as *neuer ein König, or *neuer König ein would sound like the speaker's having a stroke.

- The determiner is not at the same level of hierarchy as the complement (*the and new king is, again, the product of stroke) and rather modifies the whole unit formed by the head and the complement.

- The determiner does not add the kind of information that another modifier, such as an adjective, does. Rather, it specifies which of the individuals that neuer König represents we are referring to, simply some new king, or a more specific new king, like the one I'm pointing at.

These observations point to there being a special position for the specifier of the phrase, so rather than the linear mess of

, we'd have

, where N' represents the unit formed by the head and its complement called the head-complement complex.

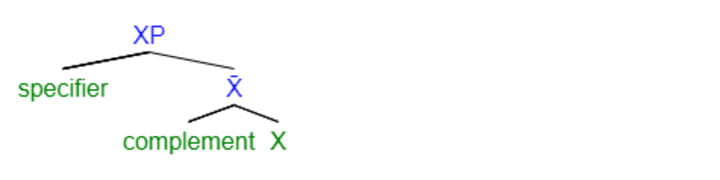

Thus, we've arrived at the fundamentals of the X-bar structure that we will now be able to apply to other phrases to eventually form a structure for the German sentence:

, where

- X represents a word or abstract parameter of X class (like N for noun, V for verb, or T for tense),

- XP stands for X phrase, of which X is the head (thus, nouns are the heads of noun phrases, Vs, of VPs, and Ts, of TPs),

- X̄ (called the X-bar, hence the name of the theory) represents the head-complement complex.

Since the bar is hard to type, I'll use X' instead.

The positions of specifier and complement can be filled by another phrase, the type of which depends on what the higher phrase allows in that specific position, for example, the specifiers of NPs are determiner phrases (DPs). It's worth noting that each node in the X-bar tree structure has 2 children (nodes below it) at max.

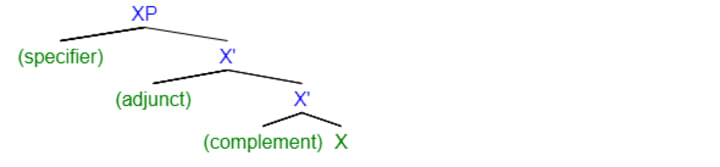

Another point we need to cover is that some phrases, like NPs and VPs (verb phrases), have a property called recursion (at least, in German, they do). We can take our friend, the new king, and add another complement-type modifier, such as the adjective phrase (AdjP) sehr großzügiger, very generous.

If we consider ein sehr großzügiger neuer König, we may see that sehr großzügiger gives a flavor not just to the king but to the whole N' (neuer König), as if the AdjP was the complement and N' was the head. It's also not a specifier (those can only be DPs), so it can only be placed under N'. If the AdjP is both a child (connected with a line to the node above it) and a sibling (child of the same parent) to N', what follows is that there must be two levels of N':

Depending on the language and on the specific phrase, the head-complement complex (X') can form as long a string as a speaker's (and listener's) working memory can fit, taking on as many modifiers as necessary. Phrases that are both children and siblings to X' are called adjuncts. Thus we've arrived at this:

Now that we have the basics, we can move on to the exciting and practical stuff.

Building a Sentence from Scratch

A noun phrase is not enough for building a sentence since we need a verb phrase, too, and it makes most sense to start from there.

Let's choose a head verb (V), like to gift. In German, that would be

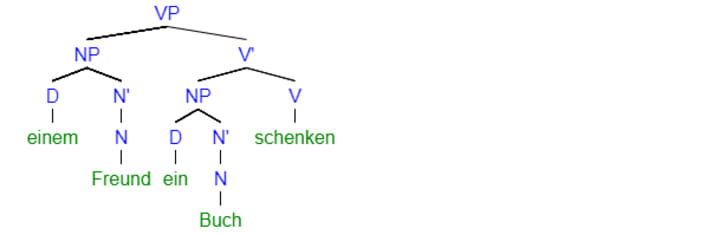

Any NP complement of V is called the direct object. The first property of German word order you need to know is that German VPs are head-final, meaning, unlike English, where the very generous new king could [VP gift his wife a book], where the verb comes first, in German, the verb always comes last in a VP (yes, always), so to gift a book would translate as ein Buch schenken:

The NP specifier of VP (remember, different phrases allow for different specifiers and complements) is the indirect object, and it, too, is located on the left side of the tree, so to gift a friend a book would be

Now, a VP in the infinitive form alone does not form a complete sentence, nor would it work if we added a NP next to it like

You would first need to inflect the verb by two properties: person (determined by the subject NP) and tense (a parameter of its own).

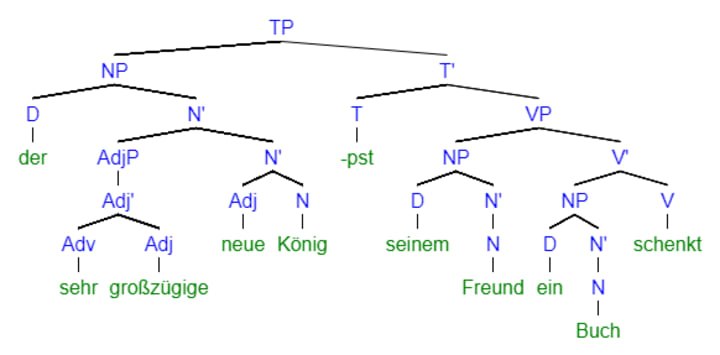

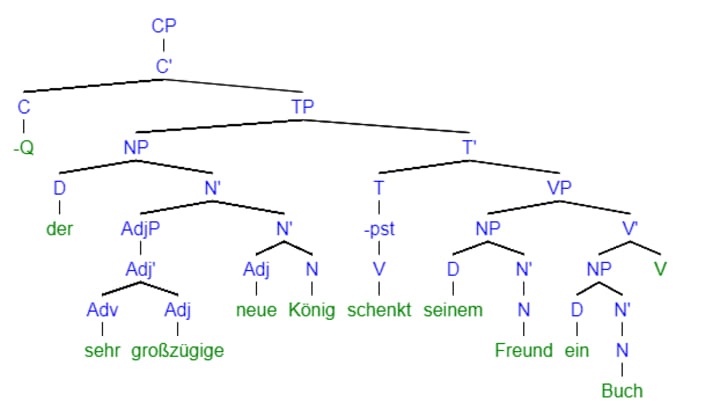

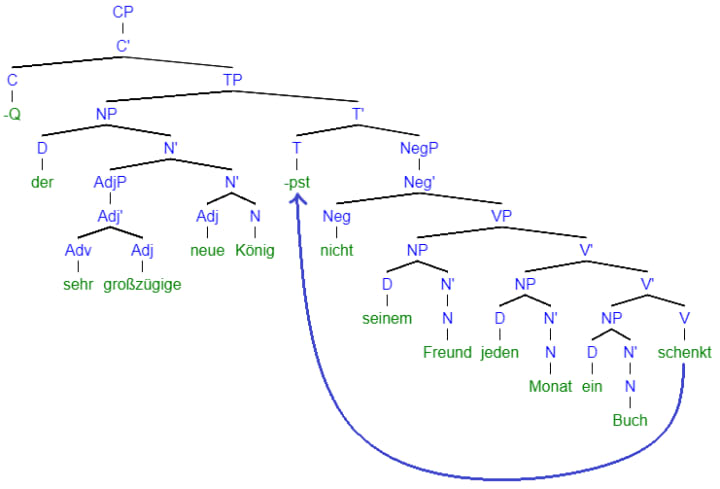

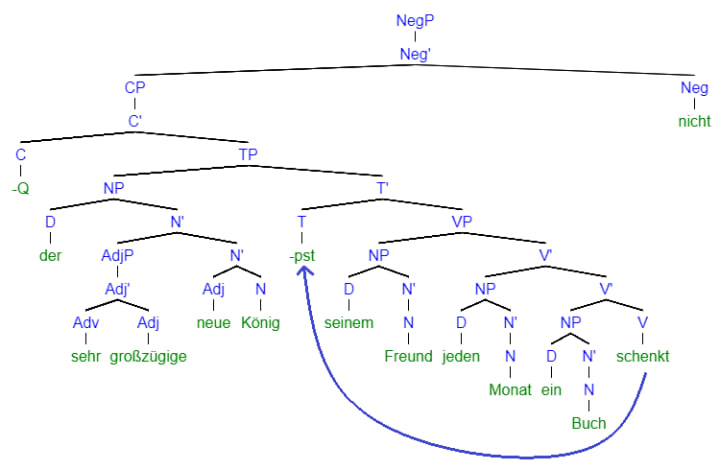

The structure that best explains it is a functional category phrase called the tense phrase (TP). In German, the head of TP is an abstract property, such as the past tense (+pst) or lack of it (-pst), which would yield the present tense; besides, it will serve as a slot for the verb to move to (don't worry about it yet). The VP affected by T is its complement. The subject of the sentence (main NP), meanwhile, will fill the position of the specifier of TP, as in the very generous new king gifts his wife a book:

- Waaaait.

Yes, you're right. If you've already tried to learn German word order, you might know that this is not a correct sentence. Not yet.

Moving from Deep Structure to Word Order

If we stuck that same TP inside a subordinate clause, forming a sentence like the country will soon go bankrupt [(subordinate clause) because the very generous new king gifts his friend a book every month], we would indeed get das Land wird bald bankrott sein, weil der sehr großzügige neue König [VP seiner Frau jeden Monat ein Buch schenkt] with the verb in the final position.

However, main clauses in German, as you might have heard, have a property called V2 order, where the verb always takes the second position after the phrase at the beginning of the sentence. To account for this, as well as subordinate clauses, questions, and inversion, we need the complementizer phrase (CP), which determines the boundaries and properties of the clause.

The head of the CP can be both an actual word, like the subordinate conjunction weil (because), and an abstract property like the (main) clause being a question (+Q) or not being a question (-Q), in the case of which it is a simple affirmative main clause. Let's start with that one.

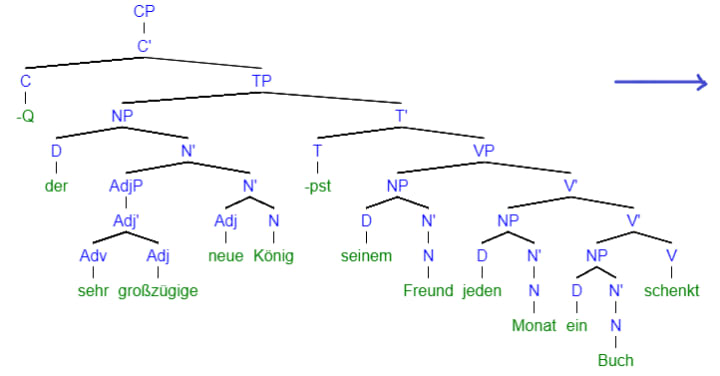

When C=-Q, you've got an affirmative main clause in its usual structure, since nothing special has been added to it. In German, this causes V to move to the position of T.

By applying this rule to our example, we get this sentence:

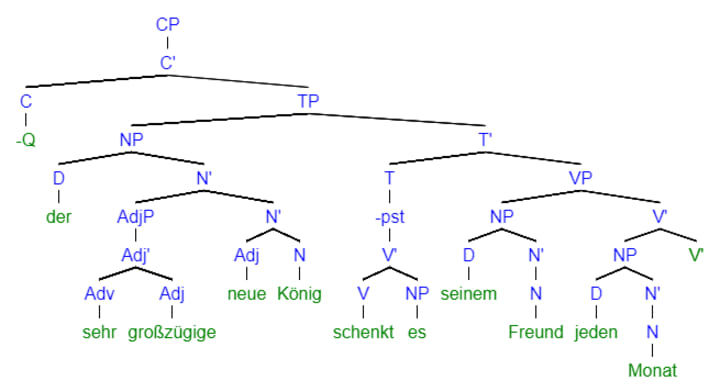

If the direct object of the verb was replaced by a pronoun, that one would tag along as well while rotating the V'. If we said that the very generous new king gifts it to his friend every month, this would happen:

Ok, how do we get from that to a question (C=+Q)?

In a yes/no question, we simply move V, which has a sleepover at T's house every main clause together with its pronoun object, to the position of C, while its pronoun object, if such exists, stays behind, as in

For a wh- question, though, you need to move not just whatever's inhabiting T but have the question word in the first position. What could be there on the left of C? The specifier.

If you're asking about the subject, though, there is no need for this move, since the verb is already resting in the second position while the question word is already in the first position, as it should be. It isn't even permitted, since the only thing you can move to the specifier of C is a modifier of V.

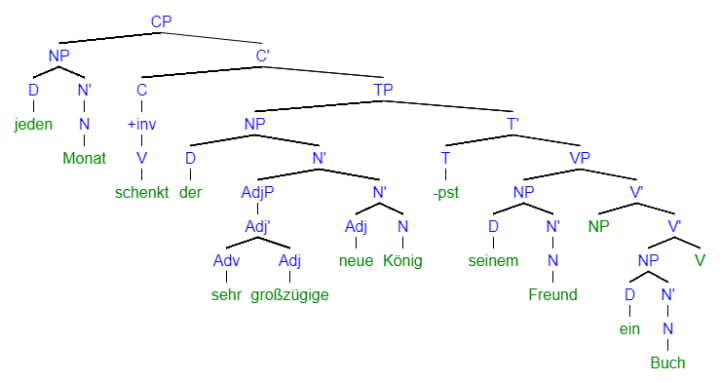

Besides this, German sentences can have an inverted structure (C=+inv) where a modifier of V moves to the first position (the specifier of CP) and the verb moves to C to occupy the 2nd position. That thing does English have, too, though only for specific situations is it reserved, so weird and poetic is the sound of an inverted clause. In German, meanwhile, inversion is used quite often for emphasis.

Finally, subordinate CPs have a subordinate conjunction, also known as a complementizer, as their head. That means that no movement happens within the clause, while the CP itself likes to move to a position on the right side of V so that it wouldn't break up a clause.

As you see in this example, when you have a VP within a VP, as when you use a modal verb to form a complex verb tense, no movements are made and the verb stays at the end as usual, although it may take a specific form dictated by the VP it's in.

Here's an example of a subordinate clause moving to a right-side adjunct of the main verb:

So far we've gone through the most important aspects of the German sentence structure, though there is one final bit of information that we still have to get to.

Negative Thinking (uh, negation) in German

German has two types of negation:

- To negate a noun, you can use a specific kind of determiner, kein, for the negated noun phrase.

- To negate any other phrase, you add nicht before it.

There is a lack of consensus around how negation is supposed to work in generative grammar, so for the sole purpose of understanding the word order, you can visualize nicht as the head of a negation phrase (NegP), the complement of which is the negated phrase, as in the picture below. It might not be the most accurate way to represent it, but it works.

If we then negated our example sentence, we would get

--> Der großzügige neue König schenkt nicht seinem Freund jeden Monat ein Buch.

OR you can negate the whole sentence, in the case of which NegP becomes head-final, as in

--> Der großzügige neue König schenkt seinem Freund jeden Monat ein Buch nicht.

Thus, we've arrived at

The General Structure of the German Sentence

How to go about learning and internalizing all of this:

- lots of input (listen to natives until correct grammar becomes instinctive),

- choose some input text and draw trees

- draw trees of sentences you're generating until the structure becomes subconscious.

We have finally covered the basic framework you need to get a hang of the German sentence structure. We could still go deeper, of course, but to keep this as short and beginner-friendly as possible (if 2.5k words count as that; I hope they do), I've only used (roughly) one example sentence, leaving out such topics as complex tenses and noun cases.

For a limited amount of time and people, while I'm putting everything together and figuring out how to explain this best in detail, I can offer up to 3 40-minute Zoom calls for a casual-style tutorship for diving deeper into the German sentence structure from an X-bar perspective, in return for a symbolic donation to my BuyMeACoffee account in support of my journey of self-studying language and sharing tools for others to do the same. If you're interested in understanding German syntax, instead of memorizing it or purely absorbing it through immersion, you can buy me a cactus 🌵 and apply in the comment, providing a way to contact you via email, Discord, or WhatsApp.

Thank you for reading! Hope you find this useful! Feel free to comment or ask questions, and good luck in your German learning journey!

About the Creator

Jūlija B.

Hey, I'm a multipassionate med student self-studying languages & linguistics and a math tutor trying to find time for music and writing, which I use as an excuse to explore anything that captivates my heart. https://buymeacoffee.com/julijab

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Masterful proofreading

Zero grammar & spelling mistakes

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (2)

Interesting!!!

Brilliant & Mind Blowing Your Concept ❤️ Please Read My Stories and Subscribe Me