The Stanford Prison Experiment

The Stanford Prison Experiment was a psychological Experiment That Studied People's Response To Power And Captivity.

Ivan "Chip" Frederick, a staff sergeant in the American Army, was having some difficulties in October 2004. His court-martial saw horrific facts about prisoner abuse, sleep deprivation, and sexual humiliation being made public. He had been one of the accused in the infamous torture scandal that broke out in March of that year from Iraq's Abu Ghraib jail.

Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo testified on behalf of Frederick and suggested that his acts were more likely a reaction to the Abu Ghraib environment than a reflection of his character. This argument is likely one of the reasons Frederick received just eight years in prison for his crimes.

Zimbardo argued that practically anyone might be persuaded to commit some of the crimes Frederick was accused of committing, including beating naked captives, defiling their holy objects, and compelling them to masturbate while wearing hoods.

Zimbardo maintained that Frederick's actions were not because he is a "bad apple," as the Army had concluded, but rather the inevitable outcome of his job.

Zimbardo was able to discuss prisoner mistreatment during the court-martial with some authority because he had personally engaged in it in the past.

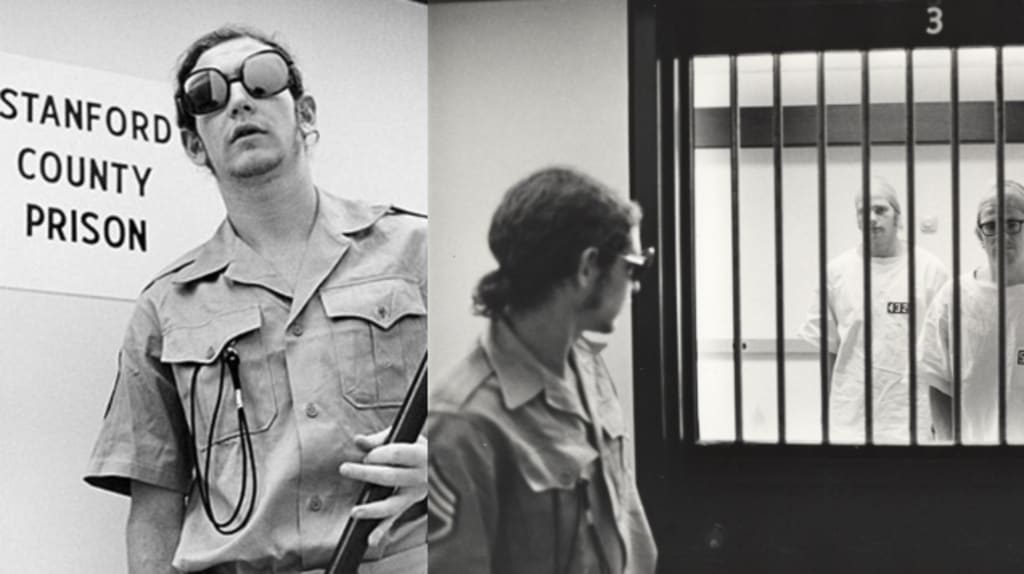

He had served as the "warden" of a fake prison in the basement of Stanford University's Jordan Hall for six days, from August 14 to August 20, 1971.

Zimbardo designed a psychological experiment that involved randomly assigning two dozen otherwise normal young men to the roles of either prisoner or guard for what was meant to be a two-week role-playing exercise in order to better understand what inspired the interactions of prisoners and their guards. The experiment was funded by a grant from the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps.

Under Zimbardo's supervision, the Stanford prison experiment degenerated into a battle between suffering inmates and manipulative, vicious guards who delighted in punishing them.

The findings were extensively publicized, making Zimbardo famous throughout his field and exposing something extremely alarming about how little it often takes to turn people into monsters.

The Beginning Of The Experiment

when the United States Office of Naval Research tasked him with researching the psychology of confinement and power as it exists between guards and their detainees. Zimbardo accepted the grant and immediately began work on the Stanford prison experiment.

The experiment was conducted in the basement of Jordan Hall on the Stanford campus. Zimbardo created four "prison cells" with internal walls, as well as a "warden's office" and numerous social places for the guards to enjoy. There was also a little broom closet, which might come in handy later.

When potential subjects applied for the experiment, Zimbardo meticulously vetted them to eliminate bad apples. Participants were denied if they had a criminal past, no matter how minor, or if they had a history of psychological abnormalities or behavioral issues.

Finally, Zimbardo had 24 healthy college-age guys with no discernible tendency toward violence or other undesirable habits. The volunteers were randomly allocated to either the prisoner or guard groups just before the Stanford prison experiment began.

Zimbardo organized an orientation briefing for his 12 guards the night before the experiment. He issued them strict orders about their responsibilities and limitations: guards would be divided into three eight-hour shifts to provide round-the-clock observation of the inmates.

As a sign of power, they were given military surplus khakis, mirrored sunglasses, and wooden batons. The guards were all advised not to hit or otherwise physically abuse the convicts, but they were also informed they may treat the 12 prisoners under their supervision however they see fit.

The following day, personnel of the Palo Alto Police Department arrived at the specified prisoners' residences and arrested them. The 12 males were brought into the county jail, searched, fingerprinted, and photographed.

They were eventually transported to the Stanford campus and led into the basement, where guards awaited them. Prisoners were issued ill-fitting jumpsuits and were instructed to wear big stocking caps. Each wore a little length of chain around his ankle to emphasize his status as a prisoner. They were divided into three groups and given a lecture on the regulations.

Every detail had been planned to make the prisoners feel subservient to the guards, including the big numbers sewed onto their jumpsuits; guards had been instructed to call convicts exclusively by these numbers, rather than by their names.

By the end of the first day of the Stanford prison experiment, both sides had fully internalized the rules and began acting toward each other as if their extreme power dynamics had always been there.

Findings Of The Experiment

The Stanford prison experiment became an immediate classic in the fields of human psychology and power dynamics. Perhaps the most astonishing findings were that the participants in the study assimilated their roles so fully that they appeared to have forgotten they had lives outside of the prison.

Guards acted with extraordinary cruelty, as if they would never have to account for their crimes, while detainees endured heinous violations of their human rights without, for the most part, seeking their release.

Perhaps more frightening, during the Stanford prison experiment, several researchers and graduate students passed down the basement, viewed the men's confined circumstances, and said nothing. Later, Zimbardo believed that about 50 individuals had witnessed what was going on in his basement prison, with his girlfriend being the only one who objected.

Just two weeks after the Stanford prison experiment ended, inmates in the famed San Quentin and Attica prisons rose up in violent revolts that were startlingly similar to what had transpired in the Stanford experiment.

Zimbardo was called before the House Judiciary Committee to testify about prison circumstances and their impact on human conduct. Zimbardo's long-held opinion was that external circumstances, rather than an individual's nature, determine how people react under stress.

About the Creator

Rare Stories

Our goal is to give you stories that will have you hooked.

This is an extension of the Quora space: Rare Stories

X(formerly Twitter): Scarce Stories

Writers:

....xoxo

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.