The Fall of Black Wall Street in Durham

An Afrocentric Perspective

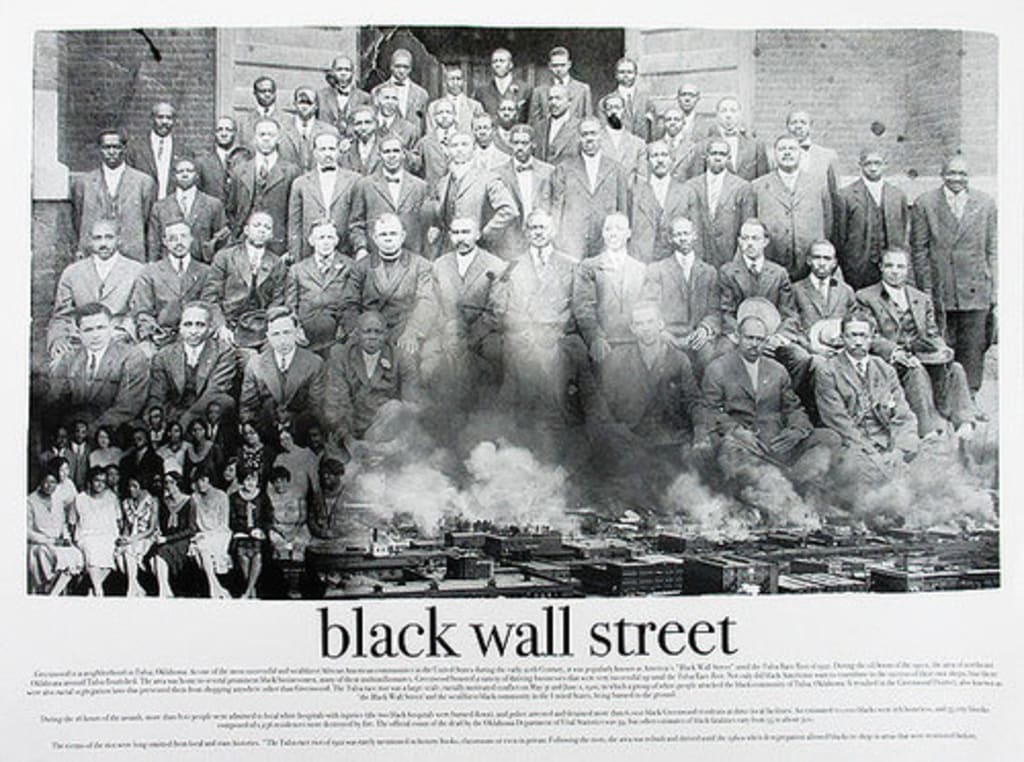

Durham, North Carolina, once stood as a shining example of Black economic independence and empowerment. At the height of the early 20th century, it was home to one of the most successful concentrations of Black-owned businesses in the country—known colloquially as Black Wall Street. It was a place where Black entrepreneurs, professionals, and intellectuals thrived, where financial institutions like Mechanics and Farmers Bank and educational institutions such as North Carolina Central University were born, all supported by a thriving, interconnected community. Yet, despite its success, Durham’s Black Wall Street eventually faltered, and its decline can be traced to a combination of external and internal forces that sought to destroy the foundations of Black economic power.

As an Afrocentric scholar, we must understand the fall of Black Wall Street through the lens of systemic racism, coloniality, and the consistent patterns of economic dispossession that have shaped the Black experience in America. The decline of Durham’s Black Wall Street wasn’t simply the result of economic mismanagement or natural market forces. Rather, it was the outcome of deliberate actions designed to undermine the collective Black economic power that had been built over decades. Understanding the fall of Black Wall Street requires examining historical documents, community accounts, and the broader socio-political climate in which these events unfolded.

Durham’s Black Wall Street was not an isolated phenomenon. It was part of a broader movement of Black economic independence that arose during the early 20th century, in the wake of the Reconstruction era and the rise of Jim Crow segregation. As African Americans in the South began to rebuild their lives after slavery, they faced an economic system that systematically kept them in poverty through disenfranchisement, limited access to capital, and lack of opportunities in the mainstream economy. In response, Black communities, including Durham’s, began to develop their own institutions, businesses, and networks of support.

The success of Durham’s Black Wall Street was rooted in the unity of its residents. Business owners, professionals, and educators worked in tandem to create an ecosystem of Black wealth, which was largely independent of the white-controlled economy. Key figures such as Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore, James E. Shepard, and Charles H. Sparrow were pivotal in laying the groundwork for this thriving community, which became known for its high concentration of Black professionals, business owners, and intellectuals.

In 1908, the establishment of Mechanics and Farmers Bank signaled the formalization of Black economic power in Durham. The bank, which provided loans and financial services to Black entrepreneurs, allowed for the creation of an economic ecosystem that promoted Black self-sufficiency. By the 1920s, Durham had one of the highest per capita concentrations of Black wealth in the country, and its Black business district was a model for Black empowerment.

Despite this economic vitality, Durham’s Black Wall Street was not immune to the forces of white supremacy and racial capitalism that sought to dismantle Black economic power. The decline of Durham’s Black Wall Street can be attributed to a combination of external pressures, particularly from local and state government policies, as well as broader shifts in the national economic and political landscape.

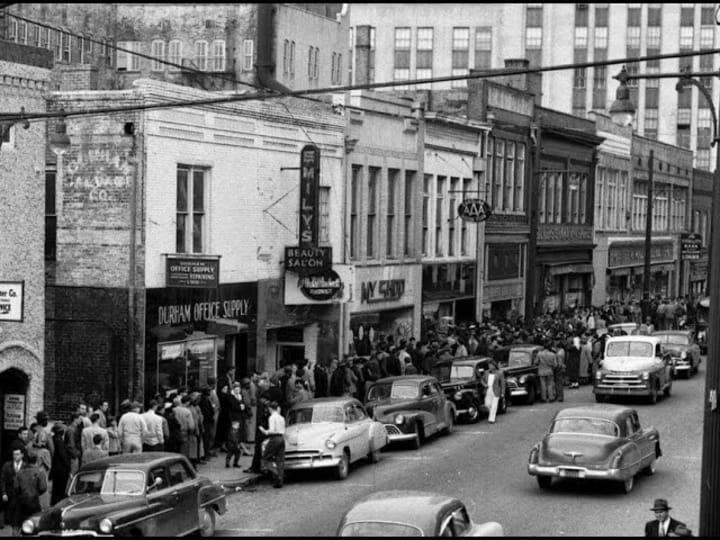

One of the most significant external threats was the “Urban Renewal” programs initiated by city planners in the 1950s and 1960s. These programs, which were often framed as efforts to modernize cities, disproportionately targeted Black neighborhoods for displacement and destruction. In Durham, the city’s Black business district, along with other historically Black areas, was ravaged by so-called “redevelopment” plans that dislocated Black families and businesses. This policy of displacement was not just about urban planning—it was about removing a thriving Black community that represented an alternative to the white-controlled capitalist system. Historical records show that local government officials, working in tandem with real estate developers, prioritized white interests in the redevelopment process, funneling resources away from Black businesses and destroying the social fabric of the community.

In addition to the physical displacement caused by urban renewal, economic forces beyond the control of Durham’s Black community also played a role in the decline. The Great Depression of the 1930s, followed by World War II, shifted the national economic landscape. The rise of industrialization and a post-war boom changed the structure of local economies across the South, with Black businesses struggling to compete with larger, corporate-run entities. During this time, the systemic lack of access to capital for Black entrepreneurs began to take its toll. Moreover, the post-war migration of Black residents to northern cities in search of better opportunities further drained Durham’s Black community of its population and talent pool.

While external pressures were significant, internal divisions also contributed to the decline of Durham’s Black Wall Street. As the community grew, so too did tensions within it. The rise of Black-owned businesses often led to the creation of a small elite class of entrepreneurs and professionals, while many working-class Black families remained marginalized. The growing gap between the wealthy and the poor within Durham’s Black community led to a sense of fragmentation, which made collective action more difficult.

Furthermore, as Black businesses in Durham grew, they often faced pressure to conform to mainstream (white) business practices and values. The rise of integration movements, while important for the civil rights struggle, also contributed to the decline of Durham’s self-contained Black economy. The push to integrate businesses and public spaces meant that Black business owners and professionals began seeking access to white-dominated markets, diminishing the focus on Black self-sufficiency. Integration often led to assimilation rather than empowerment, as many Black residents began to prioritize access to white-controlled institutions over the nurturing of their own.

The cultural and political climate of the 1950s and 1960s also had a significant impact on Durham’s Black Wall Street. The advent of the Civil Rights Movement brought about significant social changes, but it also signaled the decline of the once-thriving, self-sustaining Black business community. The rhetoric of integration, while vital for securing civil rights, indirectly undercut the idea of economic separatism that had been foundational to Durham’s Black Renaissance.

By the time of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, many of the institutions that had once made Durham’s Black Wall Street a beacon of Black economic power were either gone or diminished. Black businesses struggled to adapt to the changing economic landscape, and much of the community’s wealth had been displaced.

The fall of Durham’s Black Wall Street was not an inevitable consequence of its economic structure; it was the result of concerted efforts to dismantle Black power and the resilience of a community that had built something extraordinary in the face of incredible adversity. While the physical district was lost to urban renewal and the changing tides of history, the legacy of Durham’s Black Wall Street endures in the spirit of the community’s struggle for self-determination, its commitment to education and culture, and its continuing efforts to rebuild and reassert its economic independence.

Durham’s Black Wall Street was a testament to the power of Black people to create wealth and opportunity in the face of systemic oppression. Its fall serves as a stark reminder of the forces—both external and internal—that seek to undermine Black progress. Yet, even in its decline, Durham’s Black Renaissance has left an indelible mark on the city and on the broader movement for Black economic and cultural empowerment. The struggle to rebuild and reclaim that legacy continues, and the lessons of Durham’s Black Wall Street remain relevant today as we continue to fight for true economic justice and self-determination.

About the Creator

Sylvester Street

Sylvester Street is the publisher of Bull City Citizen, a journalist dedicated to community-driven storytelling and amplifying Durham's diverse voices.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.