The Classroom That Refused to Segregate

Tell the little-known story of a teacher or school that quietly resisted segregation laws during the Jim Crow era.

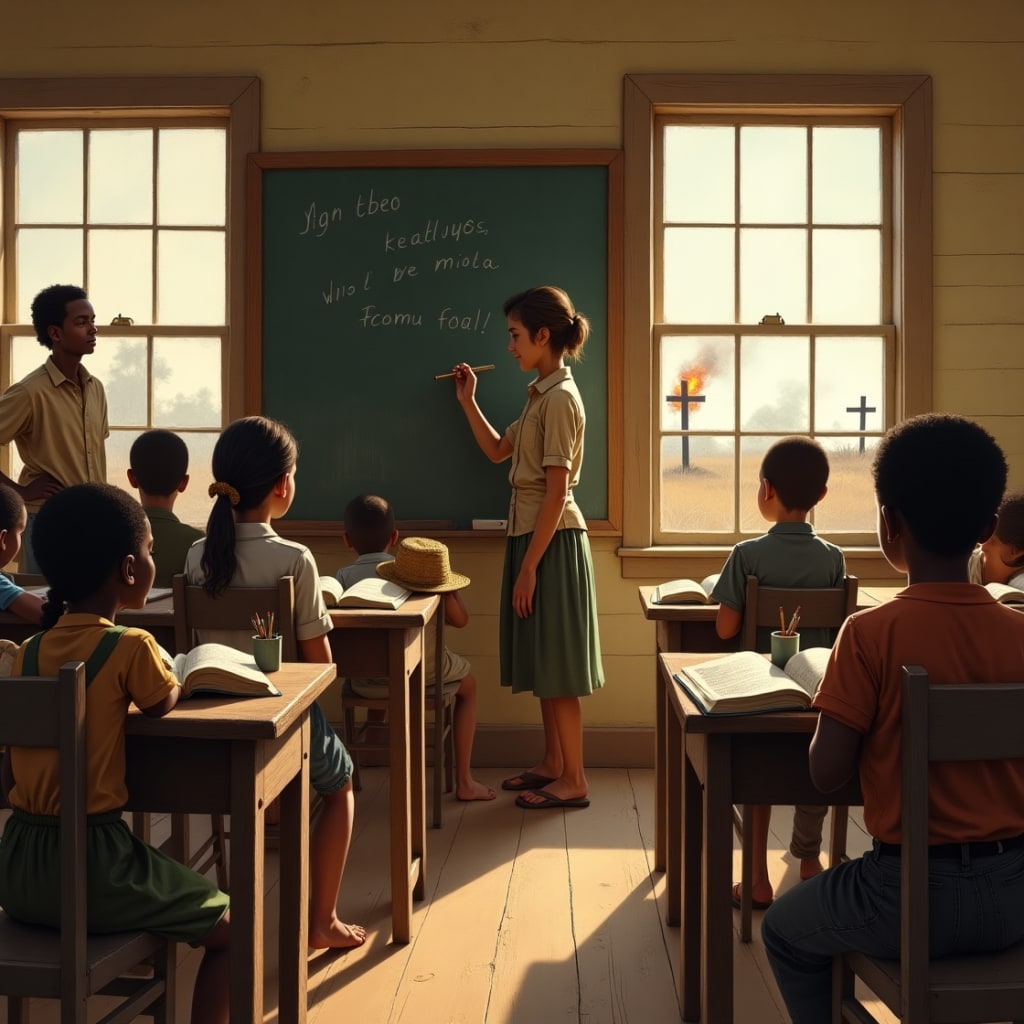

In ering summer of 1942, deep in the pine forests of Monroe County, Alabama, stood a one-room schoolhouse named Pine Hill School. The school was nothing remarkable to the casual eye: weather-beaten wood siding, a rickety bell tower, and a chalkboard perpetually coated in dust. But within its cracked walls unfolded a quiet revolution—a defiance so subtle it barely left a footprint in history books, yet bold enough to change the lives of every child who passed through its doors.

Then at the center of this story was Miss Thelma Jennings, a schoolteacher who had returned to her hometown after earning a teaching certificate from Talladega College, one of the few historically Black institutions in the South that trained educators. Pine Hill School was officially designated as a “Colored School,” a term used to enforce the racial segregation of Jim Crow. But from the very start, Miss Jennings had a different vision.

It began with a knock on her door just weeks before the school year started.

“Miss Jennings?” said the man, removing his cap and twisting it nervously in his hands. “My name’s Elijah Matthews. My boy, Henry—he’s white—but we live down the creek, and he hasn’t got no school to go to. The county closed the little white schoolhouse over yonder. Said there weren’t enough kids.”

Miss Jennings paused, her heart pounding.

She knew the law. White and Black children were not allowed to be taught together. But she also knew the realities of Monroe County: poverty didn’t discriminate. Elijah Matthews was a sharecropper, like many of the Black families whose children filled her class. And young Henry, probably no older than eight or nine, was peeking from behind his father’s leg with sunburnt cheeks and no shoes.

“I can’t promise it’ll be easy,” she said finally. “But if you’re willing, I’ll teach him.”

So began a quiet defiance that lasted nearly fifteen years.

At first, the inclusion of a white student in a Black school raised eyebrows. Some Black families were hesitant. The idea of a white child sitting beside their children, learning the same lessons, seemed dangerous—not because of Henry, who was quiet and polite, but because of what it might bring down on Miss Jennings and the community. Retaliation from county officials or the Ku Klux Klan was a very real threat.

But Miss Jennings had anticipated the risk. She didn’t make announcements. She didn’t change the school records. She simply taught, treating Henry the same as everyone else. She paired him with Jeremiah Watts for reading lessons and sat him beside Mary Lou Carter during arithmetic. Within a week, the children had stopped noticing skin color and started competing over spelling bees and who could draw the best cursive 'Q.'

Over time, other white families living on the margins began showing up at Miss Jennings’ door. There were no signs or flyers—just word of mouth and a growing trust in the teacher who made room for anyone willing to learn.

Miss Jennings enforced a strict rule: there would be no talk of hate, no use of slurs, and no discussion of who “belonged” where. “This is a classroom,” she’d say. “Not the courthouse. Not the town square. Here, we’re all just trying to learn.”

She believed, quietly but fiercely, that knowledge was the great equalizer—and that children were less poisoned by prejudice than adults.

By 1947, the Pine Hill School’s student body was about two-thirds Black and one-third white, all taught in the same room, all using the same hand-me-down books from the white schools in the county. The state education board never noticed. Or if they did, they looked the other way—perhaps because Pine Hill was remote, or perhaps because Miss Jennings’ test scores were among the highest in the county.

Still, there were close calls.

One winter, a visiting inspector from Montgomery arrived unannounced. Miss Jennings sent the white children out the back with her cousin Amos, who lived nearby, and told them to hide until the man left. She then taught the rest of the day as though nothing were amiss.

Another time, a white farmer accused her of “turning poor kids into race-mixers.” That night, a cross was burned on the edge of her property. But no one ever came closer. A quiet understanding had grown in the community—Black and white alike—that Miss Jennings was doing something rare and valuable. No one wanted to be the one to tear it down.

Her former students tell stories now—some living in Mobile, others in Chicago or Detroit—about how that little school changed them. Henry Matthews, the first white student at Pine Hill, grew up to become a civil rights attorney. He once told an interviewer: “Everything I ever learned about fairness started in that classroom.”

Miss Jennings never sought fame. She retired in 1959, just as court-ordered integration was beginning to ripple across the South. By then, Pine Hill School was too small to continue operating, and the county absorbed it into a consolidated district. She died in 1976, buried without ceremony next to her parents in a humble Baptist cemetery under an unmarked stone.

And yet, the story of that classroom—where laws were quietly ignored, where children learned side-by-side despite the odds—lives on in the lives it shaped. It wasn’t a protest march. It wasn’t a courtroom victory. But in its own quiet way, it was a rebellion—a lesson that dignity, when held firmly in the heart of a single teacher, can illuminate even the darkest corners of history.

About the Creator

Masih Ullah

I’m Masih Ullah—a bold voice in storytelling. I write to inspire, challenge, and spark thought. No filters, no fluff—just real stories with purpose. Follow me for powerful words that provoke emotion and leave a lasting impact.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.