Scissors. Hot glue. GET OUT OF THE WAY!

How crafting a maker space for kids made me smarter and revealed the powerful intellect and creativity of kids.

I had such hopes the day I attended my junior high school tour. I saw a laboratory with phenolic counter tops, sparkling glassware, Bunsen burners, and a teacher demonstrating neat stuff. So cool, I thought. We are going to do experiments and make things and learn. That teacher wasn’t cool, the glassware wasn’t for us, and we couldn’t touch anything. I don’t think we learned anything either. My grade 9 science teacher was hired because he had been a pro football player and would hopefully create a winning team. He had no teaching credentials and it showed.

In grade 10 I choose art as an elective, and for the first time I was making something in the process of learning. Being the early 80s, we didn’t talk about maker spaces, but this is what the studio was to me. I was certain I had found my future path.

At the end of high school, I ran into an all-too-common family dynamic. In trying to appease my parents, I passed on art school and studied Art History instead. Not surprisingly, it didn’t go very well. The studio art department was upstairs. I imagined the scene above my head and while I found my studies interesting, I longed to be part of all that creating. I persevered with art history but in my fourth year I was diagnosed with clinical depression, and I just stopped showing up at school. It took several years before I got myself back on track.

When I emerged from the tunnel of depression, I remembered my passion for photography and decided to turn it into my profession. Photography is a tough road, and for me it had its ups and downs, but I had a body of work, people liked it, and I had created it.

Around the same time, I discovered the diy audio community where people would gather to discuss building their own audio equipment and share projects. As I explored my own projects and began to learn, I found myself understanding the physics and math that had filled me with loathing during my school years. I started to think of myself differently. I began to realize that not only did I need to make things, but that I loved physics and math and it was exhilarating to solve problems and develop understanding of things that had always amazed and befuddled me.

While I had learned a lot, I still didn’t have tools and a shop. When I found a notice posted about a group of people who had come together to share tools and interests, I thought I should check it out. They had a weekly meeting where non-members could come, and when I walked in, I knew I needed to be part of what these people were doing. People were making all sorts of things. Anything really.

By this time, I had a five-year-old son who was proving to have a great curiosity about everything. I was standing in the maker space one day when I realized that the spirit of a maker space and the maker movement is exactly how we should facilitate children’s curiosity and their desire to make things. At that moment, I knew I had to start a kids maker space.

My wife and I knew nothing about how to create a kids maker space. While the open ended, collaborative, make whatever you want ethos of the maker movement seemed like the spirit I wanted to share with kids, the idea of a room full of 8-year-old’s who had been told “do what you want”, didn’t seem like a recipe for success. In fact, the prospect of losing control of room full of kids armed with scissors and hot glue guns was terrifying. We resolved that we would not allow things to get out of control.

We were invited by the School Council to organize a session with kids from our neighbourhood. This would be our first trial. We created an elastic-band-powered propellor car, complete with 10 pages of written instructions and photos of how to build it. We handed out 8.5x11 envelopes with the building parts and the instruction. Building parts were spilled out on the table. Instructions did not see the light of day. Those that did make their way out of the envelope fell to the floor and were kicked aside. We felt the panic rising. Our first protection against a room full of out of control 8-year-olds had failed. To my surprise, the kids did just fine without our printed instructions. They looked at the model we had brought, looked at each other’s work, and asked questions. These kids were resourceful.

Our first session with paying participants was held after hours in a daycare facility run by a friend. Every week, I would go to the maker space and fiddle with ideas until I had something we thought the kids would like. Our first project was a catapult made with a plywood arm, a tea strainer and elastic bands for power. Another week we drilled holes in mint tins, pushed LEDs and a toggle switch through the holes and wired it all up to a battery to make a simple circuit. In the process, we explained circuits, polarity, short circuits, conductivity and resistance, LEDs, batteries and switches, and not one face glazed over.

We crafted projects that we would go on to build with hundreds of kids. Hexbug mazes with various obstacles, spinners, gates and ramps for the bugs to traverse. A mini pinball game that had laser cut wooden parts and used machine springs and dowels to make the plunger. An operation game with tweezers connected to a simple circuit with a buzzer or a light bulb and a sheet of tin foil under card stock with the “patient” that kids would draw. A projector made from cardboard with a magnifying glass for a lens attached to a cardboard “bellows” for focusing. The kids would draw pictures on acetate and project them onto the wall.

Eventually we rented a space full time and planned out summer camps. We knew this would be a critical source of revenue to keep ourselves going, but we had never had to keep kids busy for 8 hours a day, 5 days a week. The old panic crept back. However, we found that in a room full of glue guns, scissors, building materials and the right kind of mentor, there is no chaos. In fact, there is hardly any talking.

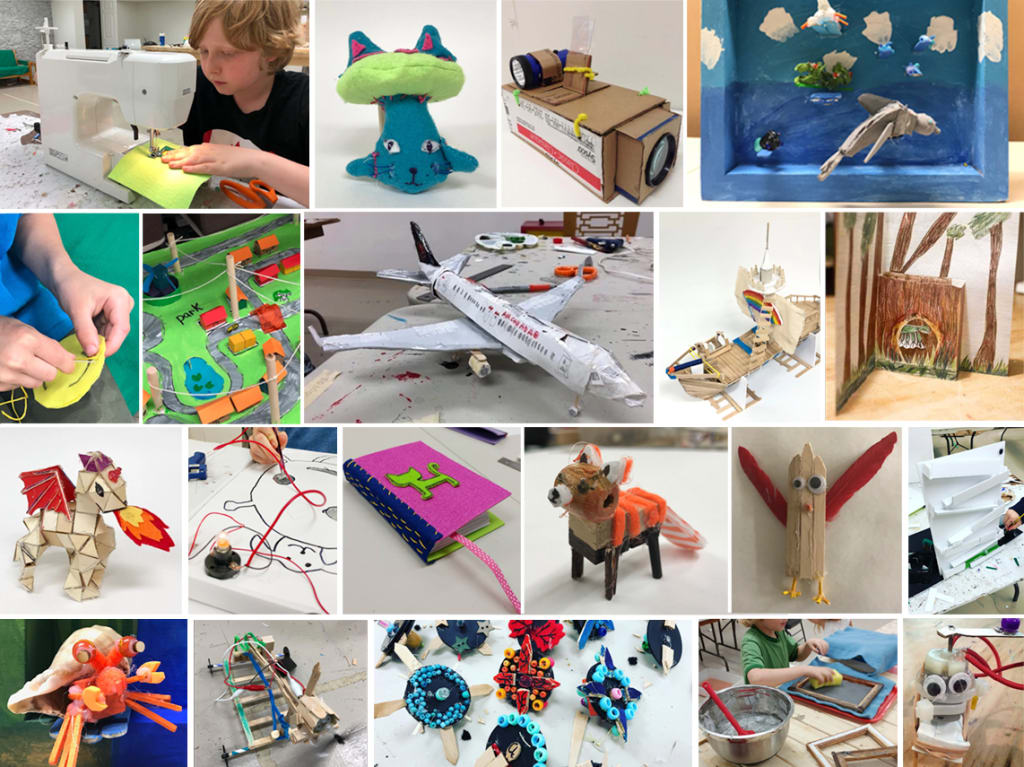

Instead of the chaos, we started to see kids creating amazing projects. We quickly came to realize that if you got out of the way, most kids would build all day. I would step back and look at the room and see 15 heads down, working on their own ideas, and not a peep from any of them.

It can’t be overstated how simple the formula was.

Scissors. Hot glue. GET OUT OF THE WAY!

We heard it again and again. A new kid would come in the door and say, “What are we making today?”

“Whatever you want.”

“REALLY?”

So, if the most important thing is to get out of the way, what did we provide? We always had back up projects, we got to know the right things to show a kid to inspire them. "Look in that book." "Go ask Finn what he is building." We found that usually one guided project was enough and then they would start coming up with their own ideas. I spent a lot of time cutting things that were too thick to cut with scissors, and we had a drill press that only I was allowed to use, but they had to draw where they wanted the hole.

The most important role though, was as a mentor creator. At summer camps I would always hire a helper, and part of the job description was to make things in front of the kids. It didn’t really matter what it was, as long as the kids saw us making things too. I especially liked to make a big production when we adults didn’t know how to do something, and we would have to look it up or figure it out. I felt it was critically important for kids to hear the adults around them say, “I don’t know, but let’s find out.”

It wasn’t just the kids who were growing. The act of crafting things with my hands, every week, from concept to completion, and sharing this with our kids, had an effect on me. Like most of us, I had heard a lot about how mental decline can occur around midlife, and I had come to believe that creativity faded as we got older. After a couple of years of creating and building projects for our sessions I started to become aware that it was getting easier to create and envision how designs should work. In fact, I told my wife one day that I couldn’t think of a time in my life when I felt more intellectually limitless. I could almost instantly imagine mechanisms for things I wanted to make and could go straight to the tools.

Most importantly, I’m a dad. What I saw in my son, who had inspired the whole thing when he was 5 and had been to more sessions than any other child, was proof of concept for me. One of the first hot glue projects we ever did with Finn was gluing googly eyes and sticks onto small wood blocks. We called them glue guys. Finn would often make glue guys, among many other things. He didn’t always show me his creations and one day my wife came up to me and asked me to look at what Finn had been making. She showed me a pile of glue guys, barely reminiscent of their humble origin. One was firefly with a protruding bead that represented its glowing abdomen. The whole rear could retract by sliding a matchstick lever as if the firefly had stopped glowing. A tiny mechanical, transforming firefly made of beads, wood and glue. It was amazing. There was a tiny fishing boat with a cast net that was full of little fish represented by very small beads. He had made an entire aquatic scene with a jumping dolphin, flying fish and a hermit crab, mostly out of garbage and paint. There was a whole arsenal of “Beyblades” style battle tops that had intricate patterns, perfectly balanced to spin, made of out beads and cut popsicle sticks. Who taught him to do this? He did it himself.

And what did I do? My greatest project wasn’t a work of art like I would have imagined when I was young. I crafted a room, a mostly empty room with tables, scissors, hot glue and cardboard. I crafted a room full of crafters. And inventors. And problem solvers. And the most creative minds I’ve been around. A hundred 8-year-olds making the exact same discovery about how things go together – each one on their own, for themselves. And it was amazing.

A lot of things changed in 2020. I talk about our project in the past because that is where it is for now. When the country shut down, we gave up our space and closed up shop. I’m grateful I learned what I did when I could. That room, full of scissors and hot glue, made me smarter. It revealed to me the powerful intellect and creativity of kids, not least of which, my own.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.