How to Read Polyphonic Music on the Piano

Monophonic and Polyphonic Music

In music theory, music is categorised into monophonic and polyphonic. According to the definition, the difference lies in the maximum number of sounds occurring simultaneously at any given moment in the piece. So if there is only one sound present, we call it monophonic music, but if there are two or more at the same time, we call it polyphonic. We commonly refer to these individual notes as “voices” or “parts”, therefore, a monophonic piece should have only one part, but polyphonic music will have two or more.

Instruments such as the piano, guitar or harp are considered harmonic instruments and they are suitable for polyphonic music because they can easily produce more than two sounds at a time. In contrast, others such as the flute or clarinet are known as melodic instruments, and they are preferred for monophonic music because they can naturally produce only one sound at a time.

What is the difference between these two types of music when reading a score?

In principle, monophonic music is easier to read because, once the initial note is located, reading consists of following the development of the melodic line. Given the starting note, there are only three possible continuations: the following note can be the same as the initial (repetition), higher (ascending) or lower (descending).

In polyphonic music, on the other hand, we have these three possibilities, but we also have to pay attention to the changes of each of the other voices and their relation with the rest.

Concretely, let us consider the movement of one of the voices with respect to a second one. We can observe that there are four possibilities:

1. Both voices move in the same direction by the same interval («Parallel motion»).

2. Both voices move in the same direction by a different interval («Similar motion»).

3. The voices move in opposite directions («Contrary motion»).

4. One of the voices stays in place, but the other moves («Oblique motion»).

These are called «contrapuntal motions», and they are a key concept in counterpoint and an essential piece in the art of composition.

Absolute vs Relative Reading

When we learn how to read a music score, we learn how clefs work and how to find out which note to play first. This way of reading can be considered «absolute» since the reference we use to find which note to play is always the same: the note that the clef gives us. The problem with this is that it requires a lot of time and effort because we need to constantly go back to the same reference point for all the notes. However, on the positive side, its main advantage is that we are usually more confident that we are playing the right note as we took the time to check it.

The «relative» reading differs from the previous one because the starting point is always the last played note, so the point of reference is constantly changing. The way of proceeding is to measure the distance to the following note using intervals and think about how many notes we need to move on the instrument accordingly. The disadvantage of this type of reading is that we can make mistakes and fall on a different note when calculating distance. Typically, we will only calculate the interval and play the note without checking again against the clef. Despite this, it has the advantage of being faster and that we can remember specific rules that allow us to guess what the next note will be with some accuracy.

Before reading several parts simultaneously, it is essential to know how to read only one properly, as naturally, when we play more than one part, the same process will be still applied to the individuals.

One of the main ways to read a simple part faster is using the aforementioned intervallic approach.

Intervallic Reading

Now that we know relative reading is preferred over absolute, let us see how to apply the intervallic reading. As we use the relative reading method, we need to use intervals to measure the distance from the current note to the next one. In a sense, the intervallic approach is one way to practise relative reading, but there could be more.

Recognising the Intervals

The Second (or Step)

Being the smallest interval different from the original note, it is also one of the easiest to spot. It consists in moving from one «field» (line or space) to the one immediately next to it, ascending or descending. Naturally, the fields will alternate from line to space or space to line. We can remember this interval as the smallest alternation of fields.

The Third

This interval is perhaps the easiest to recognise because it is the nearest equal field. So, if we are reading a note on a line, the next line above or below is a third. The same applies to spaces.

The Fourth

We can think of the fourth as the smallest skip between alternating fields.

Reminder: any interval bigger than a step is considered a skip.

The Fifth

When reading a fifth, we move between equal fields but skip one of the same kind. Alternatively, we move up or down two times the same field.

The Sixth

When reading larger intervals like the sixth, sometimes it is helpful to use smaller intervals as a reference. In this case, we can try measuring an imaginary fifth and then move one field up (or down, depending on the direction). If not, the six can be remembered as the second skip to a different field.

The Seventh

Similarly to the fifth, we can recognise a seventh as moving between equal fields but skipping two of the same kind.

The Octave

Being one of the hardest to recognise along with the sixths, to spot an octave, we can think that it is the third possible skip to a different field. Another tip that helps is remembering that it is the largest skip that occurs naturally in music. The ninth or tenth are much less frequent, so you can always suspect it should be an octave if the interval is noticeably large and on a different field. It is OK to use absolute reading with this interval until you become more confident with the recognition.

How do we start reading polyphonic music on the piano?

Now that we know how to read one part properly and the existence of the contrapuntal motions, the polyphonic reading will consist in applying these two notions simultaneously.

But before starting, a necessary precaution. When reading piano music, we must remember that if both hands are placed on the keyboard, moving the same fingers will result in playing in a contrary motion (!). This is particularly tricky for beginners because one of the most used motions is the parallel, and, instead of what we expect, it requires playing with “opposite” fingers. This happens because our hands are symmetrical but like a mirror.

Now, we can start by taking a look at some examples.

This is a very famous and one of the most challenging piano pieces in the world, yet, the beginning of the piano part is quite simple. Let us apply what we just learned.

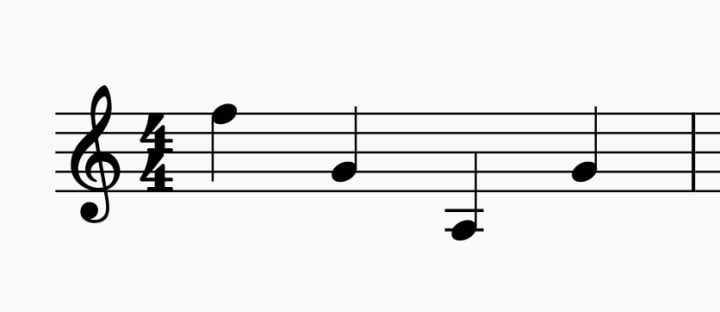

We will take the second note as the initial, as the musical phrase starts from that point.

After recognising the first note in both hands by checking with the clefs, we know that we need to play D in both hands. If we continue reading the right hand, we see that we need to move up by one line. Remembering the intervallic reading, we know that moving from a line to the next is a third, so we will play the note F accordingly.

Now we will look at the left hand, and by following the same logic, we immediately notice that it is also moving up by a third. By taking a closer look at both hands, we can observe that they will be playing the same notes in both hands all the time. This was called parallel motion, and it means that we can follow only one hand, say the right, and play the same notes on the left hand instead of reading both.

If we continue reading the right hand, the next note moves down by only one field; therefore, it is alternating, and we need to step down to the E. The same happens with the following notes until the minim D. After the D, we spot that we have an ascending skip, and if we look at lines and spaces, we recognise that it is the smallest one to a different field. So it is a fourth. We go up a fourth to the G, and then we notice that the rest of the melody moves by steps. So we should not have a problem finishing the reading.

Of course, the hands will not always play in parallel motion, and in this new example, we have a combination of all the contrapuntal motions!

We can approach this piece without a problem by using the intervallic reading and the contrapuntal motions.

The way of proceeding is finding the first note in both hands and then following the development of the lines both horizontally (intervals) and vertically (motions). The most significant advantage of this method is that we are not thinking in terms of notes but in distances that are easy to remember.

Looking at the score, we identify the first note of the right hand, C, and the first of the left, C as well. We notice that the fingerings are different, so we need to use finger 5 for the left and finger 4 for the right. Following the continuation, we see that we are moving downstep in the right hand and upstep in the left, so we are doing contrary motion - sometimes we refer to this as «closening» or getting closer between the voices.

Carrying on with the music, the following note in the right hand is again moving upstep, but this time the left hand is also doing the same. This means we are doing similar motion. The next one is tricky because the right hand moves down from line to the next line (‘nearest equal field’, it is a third), but the left goes up by one step. So in a way, we are «closening» the distance but irregularly. We must calculate this difference by choosing the correct fingers. Then, we notice that the left hand is not moving, and the right is going up upstep. This was called «oblique motion». So we will hold the left hand and move up a step with the right. Now, we recognise that both hands are moving in the opposite direction, therefore, we use contrary motion, moving up a step with the right and downstep with the left. After that, we have a different situation as the right hand is doing a skip two equal fields down (fifth), and the left is only moving downstep. We called these motions «similar» because they are not strictly the same interval, but both parts move in the same direction.

We will not continue until the end of this excerpt, as it was used only to demonstrate this reading technique. However, we can see that thinking in terms of intervals and motions simplifies a lot of the task and not only that, but we will better understand what is happening with each voice and how it is developing.

To sum up, by using the intervals and the motions, we will improve our reading speed and facilitate the job by focusing on the movement of the parts, to start reading polyphonic music in a more organised and effective way.

Francisco Pieklo: Author

About the Creator

Madeline Miller

Madeline Miller is a writer and blogger.

Comments