From Renegades to Gangs: The Transformation of Graffiti in the United States

How The Graffiti Underworld Evolved

Graffiti is one of the most visible and controversial forms of public expression. It is a language of rebellion, creativity, identity, and sometimes fear. In the United States, graffiti has undergone a major transformation—from an underground renegade art movement in the 1970s to an activity often associated with gangs, territory, and violence by the late 20th century. Understanding this shift requires looking at the cultural, social, and economic forces that shaped graffiti’s evolution.

The Birth of Modern Graffiti: Rebellion and Identity

Modern graffiti culture in the U.S. is often traced back to New York City in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Young people, many from marginalized communities, began writing their names or “tags” across subway cars and walls. Writers like TAKI 183 and CORNBREAD became famous for their ability to make their names appear everywhere (Castleman, 1982).

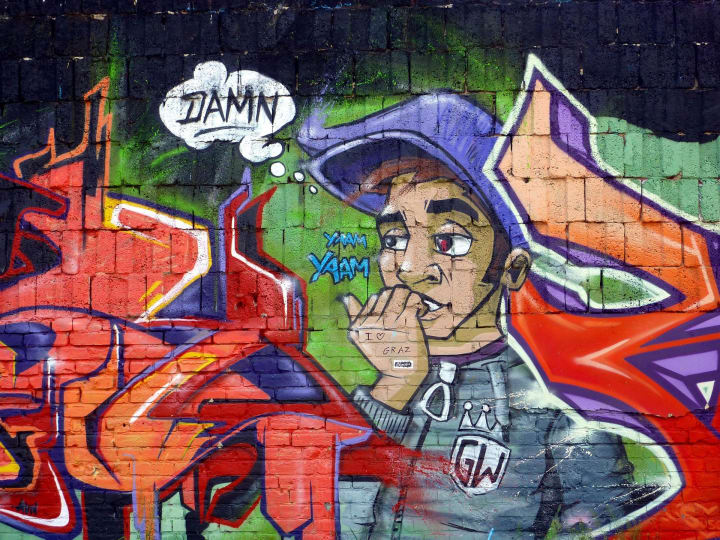

At its core, graffiti was about identity and visibility. For youth who felt invisible in a city plagued by poverty and inequality, graffiti was a way of claiming space and saying, “I exist.” The bold colors, stylized letters, and intricate murals that followed transformed graffiti into a unique art form and cultural movement (Gastman & Neelon, 2010).

During this era, graffiti was seen less as criminal activity and more as urban rebellion—an act of resistance against authority and conformity.

Hip-Hop and Graffiti: A Cultural Alliance

Graffiti quickly became one of the four foundational elements of hip-hop culture, alongside DJing, MCing, and breakdancing. Artists such as Lee Quiñones and Lady Pink turned graffiti into large-scale murals that told stories of struggle, pride, and creativity (Chang, 2005).

By the early 1980s, graffiti had captured the attention of galleries and collectors. Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring emerged from street art scenes, blurring the line between vandalism and fine art. For many, graffiti symbolized raw talent and authenticity in a city that often silenced marginalized voices.

The Shift: From Art to Territory

By the late 1980s and into the 1990s, the narrative around graffiti began to shift. Cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago cracked down on graffiti, linking it with rising crime rates. The “broken windows theory,” popularized by Wilson and Kelling (1982), argued that visible signs of disorder, such as graffiti, encouraged further crime. This perception led to aggressive anti-graffiti campaigns, including Mayor Ed Koch’s war on subway graffiti in New York.

At the same time, gangs began using graffiti as a tool for communication. Instead of artistic expression, gang graffiti often carried coded messages about territory, loyalty, and threats (Phillips, 1999). Tags, symbols, and colors became markers of turf, warning outsiders and rival gangs to stay away.

Gang Graffiti: A Different Language

Unlike the flamboyant murals of the 1970s graffiti writers, gang graffiti was usually simple and direct. It marked boundaries, memorialized fallen members, and broadcast power.

In Los Angeles, for example, gang graffiti became so prevalent that law enforcement agencies began cataloging symbols to track rivalries and predict conflicts (Police Executive Research Forum, 1996). Scholars have argued that while artistic graffiti sought recognition from peers in the art community, gang graffiti was about survival, intimidation, and control (Ley & Cybriwsky, 1974).

This shift caused much of the public to conflate all graffiti with gang activity, even though artistic traditions and gang inscriptions were distinct.

Graffiti Today: Between Art and Crime

In the 21st century, graffiti continues to live in both worlds. On one hand, street art festivals, legal mural projects, and artists like Banksy and Shepard Fairey have elevated graffiti to a celebrated form of global art. On the other hand, gang graffiti remains a serious concern in many urban neighborhoods, where walls still tell stories of territorial battles and community struggles.

Cities now try to balance these two realities: cracking down on vandalism while embracing graffiti as cultural heritage. Programs like Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program have transformed graffiti hotspots into community art projects, demonstrating graffiti’s potential for positive expression (Mural Arts Philadelphia, 2020).

Final Thoughts

Graffiti in the United States has never been just about paint on walls. It has been a reflection of identity, culture, rebellion, and power. What began as a renegade art movement rooted in self-expression eventually became entangled with gangs and urban conflict, reshaping how society perceives graffiti.

Today, graffiti stands at a crossroads: part celebrated art form, part urban battleground. To dismiss it entirely as a crime ignores its deep cultural roots, while to romanticize it as pure art overlooks the harsh realities of gang violence and territorial marking.

Graffiti remains what it has always been—a mirror of society, revealing both creativity and conflict in the spaces we live in.

References

Castleman, C. (1982). Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York. MIT Press.

Chang, J. (2005). Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. St. Martin’s Press.

Gastman, R., & Neelon, C. (2010). The History of American Graffiti. Harper Design.

Ley, D., & Cybriwsky, R. (1974). Urban Graffiti as Territorial Markers. Annals of the Association of American Geographers.

Musto, D. F. (1999). The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control. Oxford University Press.

Phillips, S. A. (1999). Wallbangin’: Graffiti and Gangs in L.A. University of Chicago Press.

Police Executive Research Forum. (1996). Gang Graffiti: Implications for Law Enforcement.

Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety. The Atlantic.

Mural Arts Philadelphia. (2020). Transforming Places Through Art.

About the Creator

xJRLNx

Im a dude letting out his madness with the help of Ai.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.