DSM 5 and its issues

Navigating Cultural Diversity in Mental Health: A Critique of the DSM-5

A collectivist culture is defined in cross-cultural psychology as a community that favors the group over the individual. Collectivistic cultures value personality qualities and attributes such as cohesion, harmony, duty, interdependence, collective goal achievement, and conflict avoidance. Many Asian civilizations, including those in China, South Korea, and Japan, are collectivist (Kendra Cherry, 2022) . The United States is rapidly becoming a "majority minority nation," with census figures predicting that non-Latino whites will account for less than half of the country's population by 2044. These demographic trends present a unique set of circumstances for health care organizations tasked with providing high-quality services to varied cultural groups and eradicating health-care inequities. The perspectives and practices associated with the convergence of these cultural features influence how all participants in the health care process—patients and their families, as well as physicians, administrators, and policymakers—understand sickness and contribute to take care. (Ravi DeSilva et al., 2015).

American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has been widely adopted in both Western and non-Western countries (Kass et al., 1983).

Rationale:

Mainstream researchers and decision-makers in the US and other countries have largely ignored the majority of advancements in cultural psychopathology research. Researchers' and therapists' perspectives, as well as how much they evaluate and discuss culture in the diagnostic process, have produced inconsistent and occasionally misleading results. For instance, the DSM-IV gave cultural issues greater consideration than its predecessors did, but it did not recognize the dynamic role of culture, which is closely related to the patient's social environment. Additionally, by relegating the cultural approach to solely ethnic minority, it tended to "exoticize" it. When compared to "normal issues of life," the normality-psychopathology boundaries involve cultural thresholds for all clinical populations (i.e., culture tends to affect perceptions of levels of severity, causality, or even identification and labelling of syndromes and clinical entities) (Kirmayer, 1989).

DSM and Culture:

The criteria and format used in DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, and DSM-IV-TR arose from psychiatric diagnostic traditions of North America and were crafted to be readily used by practicing psychiatrists. However, the effect of the DSMs has extended far beyond the boundaries of psychiatric practice in North America in a number of ways that have revealed limitations in the current system. The American criteria are used in research and practice throughout the world, highlighting incompatibilities with the alternative diagnostic system of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems and difficulties in applying DSM criteria across cultures (Kupfer et al., 2002). Different communities and cultures display or interpret symptoms in different ways. As a result, it is crucial for clinicians to be aware of any pertinent background data relating to a patient's culture, race, ethnicity, religion, or place of origin. For instance, in certain cultures, panic attacks are characterized by excessive sobbing and migraines, whereas in others, difficult breathing may be the main symptom. Clinicians will be able to diagnose issues more accurately and treat them more successfully if they are aware of such distinctions(APA_DSM_Cultural-Concepts-in-DSM-5, n.d.) .

Culture representation in DSM 5:

The DSM-5 defines culture as "the shared patterns of behaviors, beliefs, and all other products of human work and thought that characterize a group or society." It is important to recognize that culture is not just limited to ethnicity or race, but also includes factors such as religion, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, and geographic location. These cultural factors can play a significant role in shaping an individual's mental health and their experience of mental illness. One way in which culture is recognized in the DSM-5 is through the inclusion of cultural concepts in the diagnostic criteria for various mental disorders. For example, the DSM-5 includes a section on cultural concepts of distress, which acknowledges that certain cultural beliefs and practices may be misunderstood by Western clinicians and could be misinterpreted as signs of mental illness (Samhsa, n.d.). This section includes a list of cultural syndromes, such as "koro" in Asian cultures and "susto" in Latin American cultures, which are characterized by specific symptoms and behaviors that may be culturally bound and not necessarily indicative of a mental disorder.

One example of this is the DSM-5's criteria for diagnosing depression, which is based on a model of depression that is prevalent in Western societies. This model emphasizes feelings of sadness and hopelessness as key symptoms of depression and does not necessarily consider cultural variations in the expression of these symptoms. For example, in some cultures, feelings of sadness may not be seen as a sign of depression, but rather as a natural response to difficult life events. In other cultures, the expression of emotions may be more reserved, and individuals may not outwardly display symptoms of sadness or hopelessness. This can lead to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment for individuals from these cultural backgrounds. Condescension occurs when cultural sources are taken for granted. In order to successfully expand the gains obtained thus far, the diagnostic process—the initial stage in the clinical examination of every patient—must be adequately instrumentalized (Alarcón, 2014).

Another area where the DSM-5 has been criticized for its lack of cultural sensitivity is in the treatment recommendations it provides for various mental disorders. The manual often recommends evidence-based treatments that have been developed and tested in Western populations, which may not be appropriate or effective for individuals from other cultural backgrounds. For example, certain types of psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, may not be culturally relevant or acceptable to some individuals, and may not be the best treatment approach for them. A brief section on culture-related diagnostic issues is included in the DSM-5. However, cultural features are significantly developed when compared to DSM-IV. For instance, the DSM-5 poses problems with the idea of culturally specific syndromes (Bredström, 2019).

To address these concerns, the DSM-5 includes a section on cultural considerations in the treatment of mental disorders, which provides guidance on how to tailor treatment approaches to the specific cultural needs and preferences of the individual. However, some have argued that this section is insufficient, and that the DSM-5 should do more to incorporate cultural considerations throughout the manual, rather than just in a separate section. DSM-5 strives to provide clinicians with a practical interpretive framework to explore patients’ varied experiences and expression of mental distress, increasing the clinical significance of each patient’s ethnic and cultural context (Trinh et al., 2019).

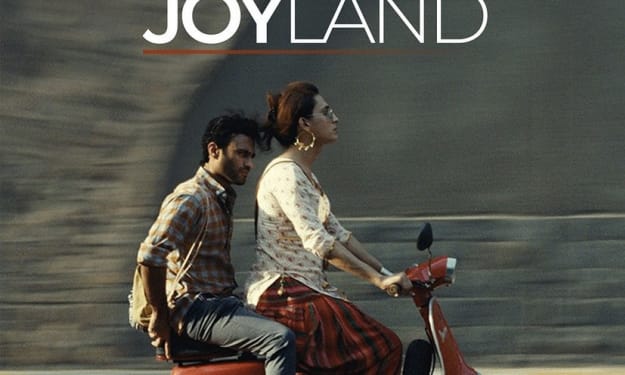

Analysis of DSM 5 in Pakistan:

According to a study, it argues that the health care system’s response in Pakistan is not adequate to meet the current challenges and that changes in policy are needed to build mental health care services as an important component of the basic health package at primary care level in the public sector (Khalily, 2011). The DSM-5 is used by mental health professionals in Pakistan, along with other classification systems such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). It is used as a reference for diagnosing mental health disorders and for guiding treatment decisions. Like in many other countries, the DSM-5 is not the only resource used by mental health professionals in Pakistan. It is often used in conjunction with other sources of information, such as clinical interviews, observations, and information from family and other sources, to make a diagnosis. It is important to recognize that cultural factors can play a significant role in shaping an individual's mental health and their experience of mental illness. The DSM-5 has been criticized for its lack of cultural sensitivity and its reliance on Western-centric models of mental health, which may not be applicable to individuals from other cultural backgrounds. As a result, it is important for mental health professionals in Pakistan to consider the cultural context of their clients and to be aware of the limitations of using the DSM-5 or other Western-centric diagnostic frameworks in a Pakistani context.

DSM-5: Clinician’s Bible or Bubble?

The DSM-5 has been described as both a “clinicians' bubble” and a “bible” due to its influence on clinical practice. On one hand, some have argued that the DSM-5 is a "clinicians' bubble" in that it reflects the biases and perspectives of the professionals who developed it, rather than a comprehensive understanding of mental illness (Derald Sue & David Sue, 2002). This can lead to a narrow view of mental health and a lack of consideration of the ways in which cultural and other factors can influence the expression and experience of mental illness. On the other hand, the DSM-5 is also seen as a “bible” by many clinicians, as it is the primary reference text used to diagnose and classify mental disorders in the United States. The manual has a significant influence on clinical practice and is often used to guide treatment decisions and insurance coverage for mental health services. This has led to concerns about the potential for the DSM-5 to have a one-size-fits-all approach to mental health treatment, and the potential for it to exclude or marginalize individuals whose experiences do not align with the diagnostic criteria outlined in the manual. In an interview with The Times, Dr. Insel said that “as long as the research community takes the D.S.M. to be a bible, we’ll never make progress.” But most of his colleagues laughed at the notion that the manual is a “bible” (Richard A. Friedman, n.d.)

In my opinion, DSM 5 is a clinicians bible because after doing a thorough research, it is obvious that not every disorder is the same for everyone. There may exist culture bound syndromes which cannot be ignored. Clinicians can use this manual as a guidebook to help them in their diagnosis but strictly following may create hindrances for them.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the DSM-5 has made some efforts to recognize and consider the role of culture in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders, but it has also been criticized for its limited cultural sensitivity and reliance on Western-centric models of mental health. While the manual has improved upon previous editions in terms of its recognition of cultural concepts of distress, it has been criticized for its limited consideration of cultural factors in the diagnostic criteria for mental disorders and its treatment recommendations, which often rely on evidence-based treatments developed and tested in Western populations. The DSM-5 is seen as both a "clinicians' bubble" and a "bible" due to its significant influence on clinical practice, but this has also raised concerns about its potential to exclude or marginalize individuals whose experiences do not align with the manual's diagnostic criteria. A cultural perspective can help clinicians and researchers become aware of the hidden assumptions and limitations of current psychiatric theory and practice and can identify new approaches appropriate for treating the increasingly diverse populations seen in psychiatric services around the world (Kirmayer & Minas, 2000).

References

Alarcón, R. D. (2014). Cultural inroads in DSM-5. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 13(3), 310–313. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20132

APA_DSM_Cultural-Concepts-in-DSM-5. (n.d.).

Bredström, A. (2019). Culture and Context in Mental Health Diagnosing: Scrutinizing the DSM-5 Revision. Journal of Medical Humanities, 40(3), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-017-9501-1

Derald Sue, & David Sue. (2002). Counseling the Cultural Diverse: Theory and Practice. John Wiley.

Kass, F., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (1983). An empirical study of the issue of sex bias in the diagnostic criteria of DSM-III Axis II Personality Disorders. American Psychologist, 38, 799–801. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.38.7.799

Khalily, M. T. (2011). Mental health problems in Pakistani society as a consequence of violence and trauma: a case for better integration of care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 11, e128. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.662

Kirmayer, L. J. (1989). Cultural variations in the response to psychiatric disorders and emotional distress. In Social Science & Medicine (Vol. 29, pp. 327–339). Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(89)90281-5

Kirmayer, L. J., & Minas, H. (2000). The Future of Cultural Psychiatry: An International Perspective. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/070674370004500503, 45(5), 438–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370004500503

Kupfer, D. J., First, M. B., & Regier, D. A. (2002). A research agenda for DSM-V. American Psychiatric Association.

Richard A. Friedman, M. D. (n.d.). The D.S.M.-5 as a Guide, not a ‘Bible’ - The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/21/health/the-dsm-5-as-a-guide-not-a-bible.html

Samhsa. (n.d.). Improving Cultural Competence A TreATmenT ImprovemenT proTocol Improving Cultural Competence. http://store.samhsa.gov.

Trinh, N.-H. T., Son, M., & Chen, J. A. (2019). 37C3Culture in the DSM-5. In N.-H. T. Trinh & J. A. Chen (Eds.), Sociocultural Issues in Psychiatry: A Casebook and Curriculum (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780190849986.003.0003

About the Creator

Fatima Haider

Experienced content writer with a versatile writing style. I create engaging copy that captures your brand's voice and messaging. My curiosity and research skills allow me to share insights that matter.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.