Building Giant Spacecraft in Earth’s Orbit: The First Step Toward Interstellar Voyages

Space

When we imagine the spacecraft of the future, our minds often conjure images straight out of science fiction: colossal vessels bristling with solar panels, sprawling habitats large enough to house thousands of people, and mile-long engines designed to push humanity beyond the boundaries of our solar system. Yet, if you were to ask today’s aerospace engineers whether we could simply build such a spacecraft on Earth and launch it into space, the answer would be a resounding no.

Modern rockets, even the most powerful ones, simply cannot carry anything remotely close to the size or mass required for interplanetary—or one day interstellar—travel. This reality means that the future of truly gigantic spacecraft doesn’t begin on Earth. It begins in orbit, piece by piece, assembled like a cosmic jigsaw puzzle.

Why We Can’t Launch It All at Once

Let’s put things in perspective. NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) and SpaceX’s Starship are currently the most powerful launch vehicles under development. At best, they can deliver about 100–150 tons of cargo into low Earth orbit. That may sound impressive, but it’s a drop in the ocean compared to what we’d need for a starship capable of carrying entire habitats, water supplies, shielding against radiation, fuel tanks, and propulsion systems. Estimates for even a modest interplanetary transport run into thousands of tons.

And size is another limiting factor. Rocket fairings—the protective shells that cover payloads during launch—have strict diameter limits. That means you could never fit a massive spaceframe or habitat ring inside a single rocket. Even if you tried, the stresses of launch—vibration, acceleration, and atmospheric drag—would likely tear a delicate structure apart before it even left Earth’s atmosphere.

In short, launching a fully assembled starship from Earth is like trying to fit a skyscraper into a moving truck. It simply doesn’t work.

The Idea of Orbital Shipyards

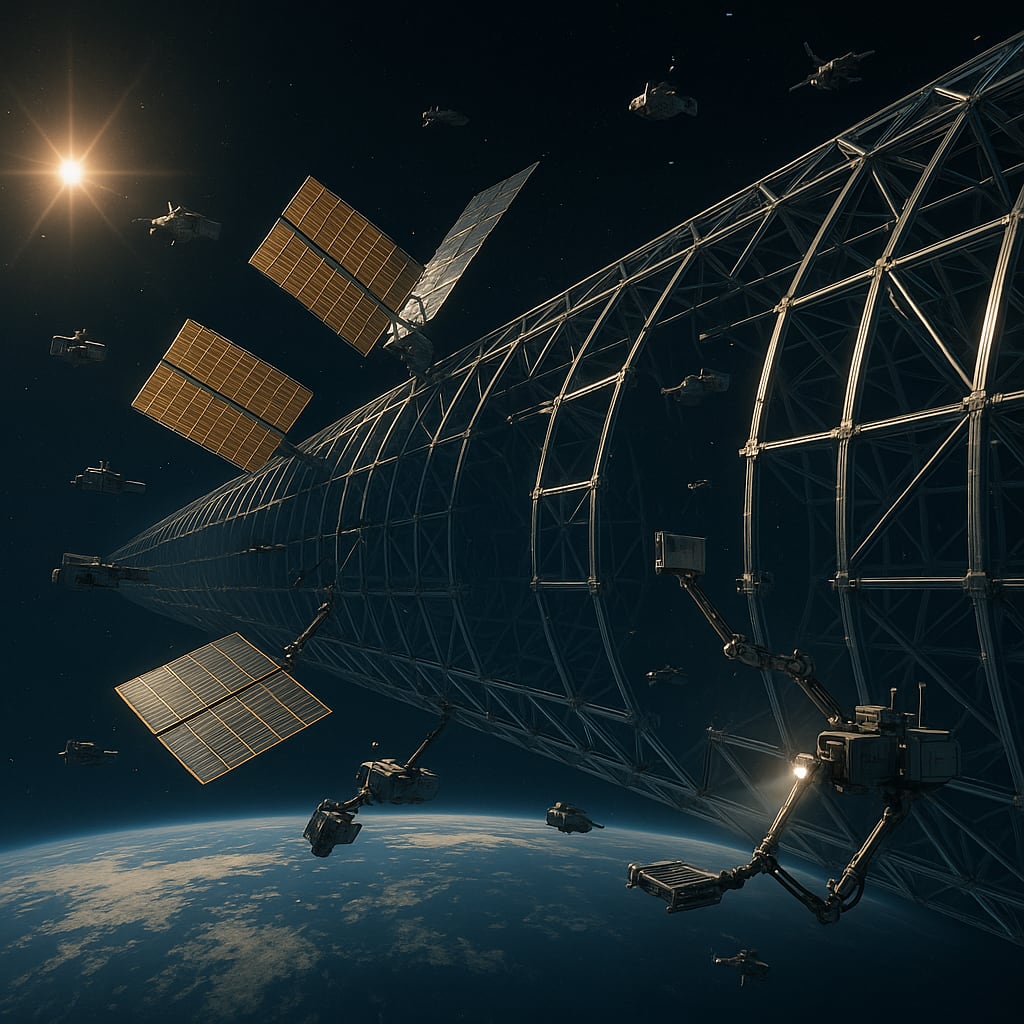

The solution is as ambitious as it is inevitable: construct spacecraft directly in orbit. Imagine orbital shipyards—vast stations floating above Earth, equipped with robotic arms, automated welding systems, and industrial-scale 3D printers. Instead of building ships on Earth and struggling to fit them into rockets, we’d send up smaller modules, raw materials, and specialized robots to piece everything together in space.

This isn’t just a dream for far-off centuries. The basic technology is already being tested. NASA and ESA have experimented with robotic assembly tools in orbit, while private companies are working on in-space manufacturing techniques. In 2019, the International Space Station successfully tested a 3D printer capable of making tools and small components directly in microgravity. Scale this up, and we could one day print entire spacecraft panels or even structural beams without them ever touching Earth’s gravity.

Building with Cosmic Resources

Another groundbreaking idea is to use materials from space itself rather than lifting everything from Earth. Consider this: mining companies are already eyeing asteroids rich in metals like nickel and iron. A single medium-sized asteroid could contain more raw metal than humanity has ever mined on Earth. Transporting that material to orbital factories could give us essentially unlimited building supplies.

Even water, crucial for life support and rocket fuel (when split into hydrogen and oxygen), might come from lunar ice or water-rich asteroids. Instead of hauling giant fuel tanks up from Earth, we could refuel spacecraft directly in orbit, dramatically reducing costs.

And of course, in orbit there is no shortage of power: solar energy is abundant, unfiltered by Earth’s atmosphere, and available almost constantly. Orbital construction yards would thrive on this endless energy supply.

What We Could Build

So what kinds of spacecraft might humanity assemble in orbit?

Massive cargo ships capable of ferrying hundreds of tons of equipment to the Moon and Mars. Imagine modular freighters carrying entire greenhouses, power stations, or ready-made habitats.

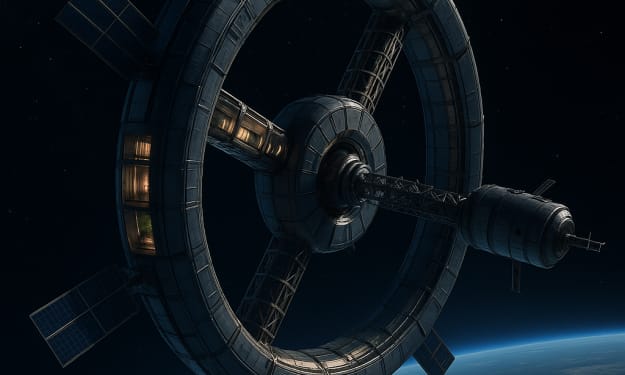

Interplanetary transports designed to carry large crews comfortably on months-long journeys. Unlike cramped capsules, these could feature rotating habitat rings to simulate gravity, shielding layers to protect against solar radiation, and entire living ecosystems.

Interstellar probes or generation ships. For any mission beyond our solar system, spacecraft will need to be absolutely enormous. Radiation shielding alone might require a hull several meters thick, and propulsion systems could span hundreds of meters.

Orbital cities. Perhaps the most exciting vision: giant stations housing thousands of permanent residents, serving as hubs for science, trade, and exploration.

The Challenges Ahead

Of course, none of this will be easy. Orbital shipbuilding raises enormous challenges. First, there’s cost—launching even modular components into orbit is still extremely expensive, though companies like SpaceX are driving that price down. Second, there’s the matter of safety. How do you weld, print, or assemble fragile materials in a vacuum where temperatures swing hundreds of degrees? And who repairs the robots when something goes wrong?

Yet, we already have proof of concept: the International Space Station itself. It is essentially a spacecraft assembled in orbit, piece by piece, over two decades, with modules launched by multiple nations and carefully connected in space. The ISS is tiny compared to future starships, but it shows that orbital construction is not only possible—it’s happening already.

Humanity’s Next Great Leap

Building spacecraft in orbit is more than just an engineering challenge; it’s a turning point in human history. It marks the transition from being occasional visitors to space to becoming true residents of the cosmos. When the first orbital shipyard opens for business—whether in 20 years or 50—it will be the spiritual equivalent of building the first ocean-going ships on Earth.

The question is no longer if we’ll build giant spacecraft in orbit, but when. And when that happens, humanity won’t just be dreaming about the stars—we’ll finally have the tools to reach them.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.