A Teaching Philosophy Thirteen (Challenging) Years in the Making

As American students (rightfully) begin questioning the benefits of a college education, what we need in our college classrooms is more honesty surrounding the myths of meritocracy and social mobility in the U.S. Here's my radical teaching philosophy, thirteen challenging years in the making.

“...Learning is a place where paradise can be created. The classroom, with all its limitations, remains a location of possibility. In that field of possibility we have the opportunity to labor for freedom, to demand of ourselves and our comrades, an openness of mind and heart that allows us to face reality even as we collectively imagine ways to move beyond boundaries, to transgress. This is education as the practice of freedom.” -bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress

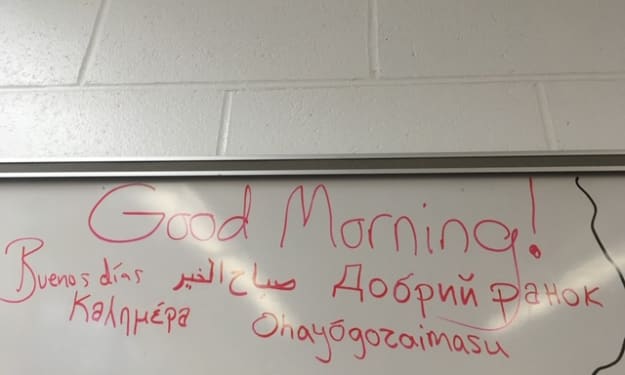

Over the years, as I have taught multiple subjects to students of all ages, backgrounds, and ability levels from the U.S. and around the world, my teaching philosophy has evolved to reflect my core beliefs about education and the responsibilities of 21st century educators. Principles of social justice, equity, and empathy have informed my teaching practice since I first entered the classroom in 2010.

My background as a first-generation college student from a working-class family has greatly influenced my teaching philosophy. As my mother ended her formal education during the ninth grade to enter the workforce full time, and my father sacrificed a college scholarship to serve in the military during the Vietnam War, I had to become an independent and self-motivated learner early on. I try as an educator to instill in my students, many of whom are first-generation college students themselves, the values of critical thinking, intellectual curiosity, and independence.

When I was a novice teacher, I believed that education was, as I’d always heard, the ‘great equalizer’. I now know that is not true. Coming to terms with the realities of the American education system was difficult and disheartening, especially as a young teacher of marginalized populations of students in a failing high school within a struggling, urban school district. Many of the college students I teach today are products of this same district, and are often completely unprepared for the academic demands of higher education. Education is not the great equalizer. The American public education system, unfortunately, often serves to maintain the status quo. As a working-class educator and former first-generation college student committed to social justice and antiracism, I reject the status quo. I am grounded in reality and do not idealize our education system. Instead, I teach my students to see the world as it is, and challenge them to do their part to make it a better place for all.

When it comes to challenging the status quo, we must acknowledge how characteristics such as race, gender, socioeconomic status and linguistic and cultural background often (unfairly) determine the educational experience that a student in the American public school system will have. I strongly believe that to be an effective educator for all students, teachers from all backgrounds must first make a sincere effort to acknowledge and overcome implicit and explicit biases and stereotypes about students from racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, linguistic, and religious backgrounds different from their own. We must also acknowledge and come to terms with the white-washed version of history that many of us were taught in school. Only then can we truly empathize with our students, earn their trust, engage in mutual respect and solidarity, and help them become fully engaged students invested in their education.

Because I’ve worked with struggling students throughout my career, I believe in meeting students where they are without sacrificing academic rigor. It is important to maintain high expectations for all students while acknowledging that not all have benefitted from a high quality, equitable education. This is especially important for minority students, students with disabilities, and English language learners. Students of all backgrounds and ability levels succeed in my classroom as long as they work hard. To be an effective educator, I also believe you must be honest with students about the purpose of education (in my case higher education) as well as the social, political, and economic realities of the world they will inherit. Many students are now (rightfully) skeptical about the value of higher education. I’m honest with my students and believe that having frank conversations about real world topics such as this engages students and allows them to see the myriad inherent benefits of education, despite a lack of true social mobility in our society and despite the stagnating wages of American workers, even those with college and graduate degrees. Education will always be empowering. Education is freedom. There is inherent value in education, even when the economic benefits don’t live up to our expectations.

When I was nearing the end of my English for Speakers of Other Languages Master’s program and was placed as a student teacher in an ESL classroom (that had previously been used as a closet) in a high-needs urban public high school, my student teaching supervisor said something to me that has influenced my pedagogical practice for over a decade. She once quipped that ESL was “taught in a vacuum.” I fundamentally disagreed with her comment. She did, however, influence me to always strive to incorporate relevant, real-world content into my language and writing teaching. For example, in my freshman composition courses, I don’t just teach college-level writing skills. My students learn how to research, how to become better writers, and how to use MLA format, but I teach them all of these skills through an underlying content theme of immigration and the immigrant & refugee experience in the U.S.

Because I have a Master’s degree in International Development and over a decade of experience working with refugee populations in educational, vocational, and immigration contexts, I am thrilled to be able to combine my passion for teaching with my passion for refugee and immigrant rights. By the end of the semester, students in my class who previously struggled to write anything at the college level have read multiple texts on immigration and the personal experiences of immigrants and refugees living in the U.S. (such as award-winning journalist Maria Hinojosa’s Once I Was You), have crafted thesis statements about the media’s influence on Americans’ opinions on immigration and immigrants, have demonstrated a grasp of the fundamentals of MLA format, have explored and written about their own ancestral roots as well as researched our city's refugee populations, and have assessed their own growth as college-level writers over a semester in my classroom. I never teach English 'in a vacuum'.

Trends in education come and go, but I have never abandoned my beliefs in the effectiveness of student-centered, hands-on learning and integration of real world topics of interest to students, as well as the once-controversial belief that education can and should be fun. Why wouldn’t we want our students to enjoy the time they spend in our classroom? As a student, I sat in enough joyless classrooms to know that rigorous content without real human connection or enjoyment have minimal effectiveness in the long term. Truly effective educators are able to incorporate academic rigor, principles of social justice, and joy into their curricula. All of these are needed in order for the transformative, revolutionary potential of education to be realized. Otherwise, what is our purpose as educators other than to maintain the status quo?

About the Creator

Brooke Elizabeth

Working-class English Educator with Expertise in Refugee and English Language Learner (ELL) Education. I have a Master of Arts in International Development, a Master's in Education, and A LOT of existential dread.

Comments