Welcome Home, Leviathan

What the comeback of lake sturgeon in Wisconsin means to me

In April of this year sensors in the Milwaukee River detected five lake sturgeon moving upriver. These are some of the first adult sturgeon returning since restocking began in 2006 as part of a multi-year effort to return the sturgeon to Wisconsin rivers and lakes. In 2021, a 100-year-old, 240-pound sturgeon was caught in the Detroit River in Michigan. Both of these rivers were once much more polluted than they are now.

The story of the return of the lake sturgeon gives me hope on so many levels.

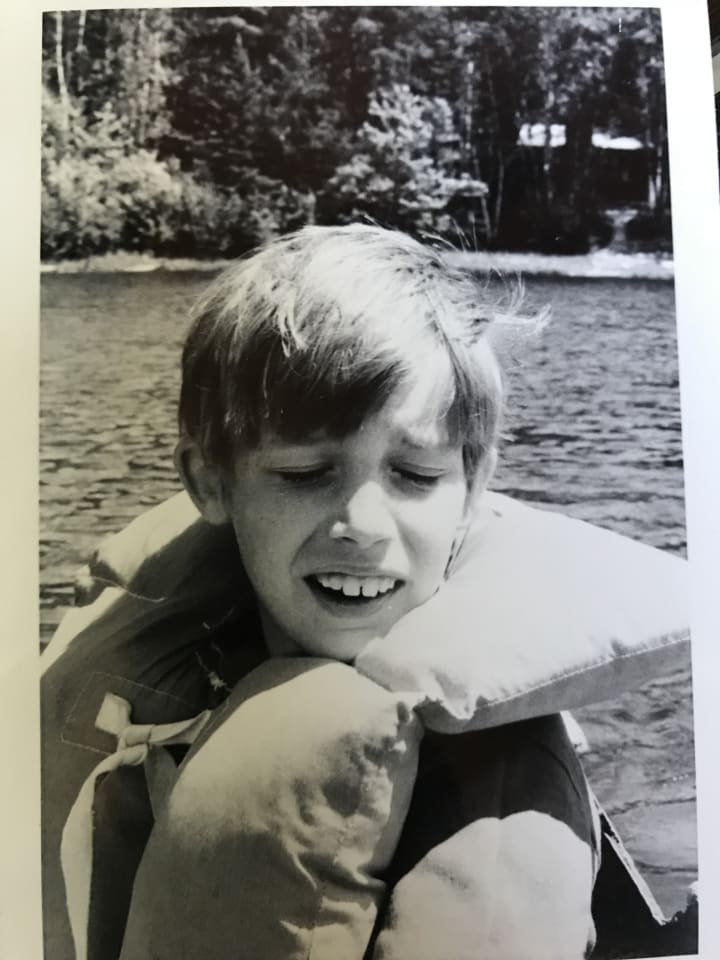

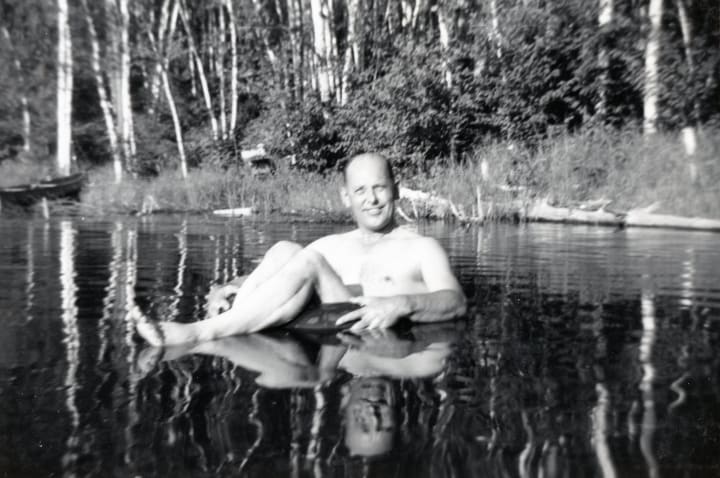

I love the fish that live near the bottom of the lake. You drop your bait down, down, down out of sight and you blindly jig, hoping the action of the lure will attract a big one. When I was a kid, I would spend many hours casting or trolling and hoping to pull an amazing fish out of the lake. Sometimes I did.

I have never fished in a place where sturgeon live, but I celebrate the return of this fish to my home state of Wisconsin and I especially celebrate the reasons for this return. The sturgeon are back because of the combined efforts of the Great Lakes States and the tribal nations who live here. They are back not just so white people like me can have the thrill of catching one, but for the healthy recovery of a non-human kin species in the ecosystem.

Before European traders and settlers came to this area, lake sturgeon had lived in the waters since before the appearance of the Great Lakes at the end of the ice ages. Sturgeon as a class of fish have existed largely unchanged for at least 200 million years (by contrast, the genus Homo has been around for about 2.5 to 3 million years). Sturgeon swam in the waters during most of the time when the dinosaurs walked the Earth, and they certainly look prehistoric. They are a cartilaginous fish, like sharks, and they have bony protective plates called “scutes” on their backs that look like dragon scales. They feed on the lake and river bottom and have sensitive “barbels” that tell them when to suck up food species unlucky enough to be in their path. Lake sturgeon can live to be over a hundred years old and can get to be hundreds of pounds and over seven feet long. Historically, sturgeon were a very big part of the Great Lakes ecosystems. Scientists estimate that before European settlers arrived, up to 90% of the biomass of the Great Lakes was composed of sturgeon.

For almost all of the time that humans have lived in the Great Lakes region, the sturgeon had been considered kin by the Indigenous people living here. The spawning runs were said to contain so many fish that a person could walk across rivers on the backs of the sturgeon. The Menominee nation in northeast Wisconsin has a rich history of celebrating the spawning run with community gatherings and the “fish dance.” Within the Menominee and also the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe), specific clans are identified with the sturgeon, which marks the sturgeon as one of the most important kin animals. The sturgeon is the spiritual protector of wild rice, the key food plant for the Menominee and Ojibwe. The spiritual importance of the sturgeon could not be overstated, but the sturgeon also is an important traditional food animal for the Menomonee and the Ojibwe, who use every part of the animal. Think of how important the bison are to the Dakota people, and we are in the realm of the importance of the sturgeon for the Great Lakes people.

When European traders first came to the region, one of the things they traded for was sturgeon meat, which was plentiful at the time. Later, when European settlers came, they built dams on many of the river systems in order to facilitate the logging and sawmill operations that systematically removed all of the old-growth forests. These dams disrupted the spawning patterns of the sturgeon and other fish. By the 1860s commercial fishing came to many of the places where the sturgeon lived. The commercial fishing methods used nets to catch smaller fish, and the sturgeon, which could grow to hundreds of pounds and had knife-like fins that could destroy the nets, were considered a nuisance fish, so the commercial fishing policy was to kill all the sturgeon in order to make their harvest easier. They would catch sturgeon and throw them on the sides of the rivers. When these sturgeon would die and dry up on the banks of the rivers, they were so plentiful that boat captains would collect them to use for fuel in their steamboats. Eventually, starting in the 1870s and 1880s, the fishing industry learned the value of sturgeon and they started harvesting sturgeon for meat and caviar and isinglass at alarming rates (up to 8.5 million pounds in a peak year!).

Between the dams, the removal by and for commercial fishing, and later, pollution from industry, the once-plentiful lake sturgeon became an endangered species in Wisconsin, the heart of its home range.

The image of using a 100-year-old fish as fuel for a boat is just one example of just how exploitative and wasteful the waves of white settlers were. Between the fur trade for white markets and the settlers themselves, they killed all the remaining bison and elk in Wisconsin, and they hunted out the turkey and killed almost all of the white-tail deer. They killed all the wolves, mountain lions, and almost all of the beavers, cranes, and bears. They made the passenger pigeon, which had once darkened the skies of Wisconsin by the millions, go extinct through hunting. They dramatically altered habitats: by logging, by digging up prairies, by stopping the burn cycles that had been maintained by the Indigenous people, by damming rivers, by building roads and railroads, and by introducing non-native invasive plants and animals.

When I say “they,” I should be saying “we” because I am an ancestor of European settlers, and I continue to live in the world they made, with some of the same extractive practices.

To the Indigenous people of this place, this wanton destruction of plant and animal life was a form of genocide. On one level it was a denial of food sources to the people who had depended on those sources for generations. For example, near where I live there was a famous “fish trap” where the Namekagon River (“Nme” means sturgeon in some of the Algonquin languages like Anishinaabeg) flows into the St. Croix River. The trap used a system of weirs to funnel spawning sturgeon into a place where people could easily catch them in baskets. That trap and others like it were destroyed by settlers in the name of river navigation and logging. On a second level, it was an attack on living beings who are considered kin. What happens to the people who live in the sturgeon clan, when there are no more sturgeon in the rivers and lakes? In that sense, it was a spiritual genocide, and we are still living in the aftermath of that attack.

Non-Indigenous folks have slowly come around to the idea of protecting wild animals and habitats. When Aldo Leopold was writing in the mid-1900s, the white-tail deer was almost gone from Wisconsin. He wrote as someone who wanted to promote conservation. He suggested that we study the deer population and limit hunting in order to grow and manage the population. By only allowing hunting late in the fall, and only killing a limited number of male deer, the population of deer could grow. As a result of these practices, the deer population of Wisconsin has reached a level where now hunters are encouraged to take does in order to limit the population. This type of protection and management of populations of wild animals has become the norm across the country. It came to include the reintroduction of species that had been lost to the area, like turkeys, whooping cranes, and elk. It was enhanced with the passage of the Endangered Species Act in 1973. Wolves returned to northern Wisconsin, as have mountain lions and sandhill cranes. Bear and beaver populations have rebounded, and many fish species are thriving.

Even as conservation efforts have brought back some species’ populations from the brink of extinction or extirpation, it is not always an easy or straight-line path. For example, the wolf’s return has been fought by livestock ranchers. And trophy hunters have recently decimated the Wisconsin wolf population, taking nearly double the quota set by the DNR, in an ill-advised 2020 hunt that was vehemently opposed by Indigenous groups.

The return of the sturgeon has been slow. Lake sturgeon grow slowly, and females do not spawn until they reach 25 years of age. In addition, they require waterways free of dams in order to reach their spawning grounds. And that water and the sediments on the rivers need to be clean because these fish feed on the bottom. Despite those issues, tribal nations and the state have worked together to foster the growth of the sturgeon population, and populations have reached a point where there can be tightly controlled fishing seasons for non-Indigenous people and self-monitored managed fishing for Indigenous people (who have treaty rights to fish out of season).

A possible impediment to the return of the sturgeon is poachers. The sturgeon are rare enough that their roe can be quite valuable for caviar. In the early days of protecting sturgeon in Wisconsin, rivers had to be watched during the spawning season by volunteers in coordination with the authorities, and fines had to be raised. A single poacher could take many sturgeon and derail decades of conservation efforts. 2022 was the first year that the state has not managed the watcher program, both because poachers are not as common anymore and because the sturgeon population has recovered from the brink, as well as difficulty finding volunteers.

One of the partnerships that have aided the sturgeon’s return is the work that the Menominee Nation has done to assist the sturgeon in getting past dams in order to spawn on the Menominee Reservation once more. This Reservation site was chosen by the tribe partly because of its importance for the sturgeon. It was a cruel irony that dams blocked the sturgeon and prevented the Menominee from continuing that relationship with their spiritual kin. Now the sturgeon have begun to return, and the Menominee celebrate the fish dance in the company of real sturgeon once more.

Why do I care about the return of the lake sturgeon?

It is interesting to me that Wisconsin currently holds the highest concentration of lake sturgeon in the world, and yet estimates are that this current population is only 1% of the pre-European settler sturgeon populations. I dream about what a full recovery of sturgeon and other species might look like.

There is a voice inside me that yearns for the recovery of wild species and ecosystems. I love hearing sandhill cranes fly overhead and I live for other stories of species in recovery, like the bald eagle and the lake sturgeon. This voice is calling to me to be part of that recovery process. I think it goes back to when I would go fishing as a child. I would imagine there was a whole world down there in the deep, beyond the realms where I could see.

Even today, 40 years later, I have frequent dreams about going fishing in a deep lake and or finding whole cities or other amazing places underwater. There is something about fishing that tugs at my psyche. If I had to say what that tug is, I would say that my surface awareness knows there is more to me than my moment-to-moment thoughts and worries, but most of that depth is inaccessible or incomprehensible to my daily-life self. I am fascinated by my own depth, even as it is a mystery. Perhaps that is why fish and fishing live so vividly in my imagination. Fish travel in the depths, and to catch one is to capture and hold something from another world.

To lose a species of fish is a loss not just for the ecosystem, but it is a loss for the depths of our collective souls. We need the deep lakes and the oceans to continue to be alive with travelers. Without that deep life, we would have no mirror for our own depths of our souls, and we might fall into danger of losing our own depths. My desire for the recovery of species like the sturgeon is a longing for recovery of my own depth and my own connections to the natural world.

I mourn the loss of sharks in the ocean due to fishing for shark fin soup. I have existential dread over the loss of the coral reef ecosystems to coral bleaching, as a side effect of climate change. I cannot handle the reports of how massive super-trawlers drag nets along the bottom of the ocean and pull up and kill tons of by-catch. The Pacific Garbage Patch physically hurts my heart. The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico is a crime. That is why any news story about the recovery of a fish species gives me more than hope. It repopulates my own depth of self. I am complete when the world is whole and thriving.

It might seem ironic that trophy fishing and Indigenous kin relationships work together to bring back a threatened species, but fishing can be a gateway to loving nature and caring for and protecting the species that one is fishing for. With fishing, there is a connection to nature that speaks to the soul and a connection to friends, family, and community that cannot be measured.

The other piece that gives me hope is the persistence of this ancient fish. The sturgeon that are here now have lived through catastrophe. That they are returning gives me hope that we can support the recovery of people and cultures, including myself.

I was inspired to find out more about lake sturgeon when I stumbled across a video of a white sturgeon in British Columbia on Facebook Reels. It was in shallow water and the massive fish looked unreal and prehistoric. My Facebook app shows me random reels interspersed with posts of friends. They must be watching which reels make me stop and watch because now about half of the short videos are of people fishing or drone footage of ocean life. Does anyone else like watching people cast and catch fish?

-------

This story was first published on May 17th, 2022 on Medium. Follow me on Medium for more essays and stories.

About the Creator

Andrew Gaertner

I believe that to live in a world of peace and justice we must imagine it first. For this, we need artists and writers. I write to reach for the edges of what is possible for myself and for society.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.