The world's largest source of battery metals is located 4,000 meters below sea level

It is generally acknowledged that the world population must transition away from fossil fuels in order to have a sustainable future. Electricity appears to be a suitable green replacement, but it has a serious drawback: there aren't enough metals to make the switch. Although we have been mining for additional metals for thousands of years, could the battery revolution still qualify as a green option given the costs of destroying forests and uprooting species to get there?

What if there was another method to obtain the metals required to create batteries? Moving mining to the deep sea, where priceless nodules known as manganese tubers can be discovered resting on the seabed as loosely as pebbles on the sand, is one potential option.

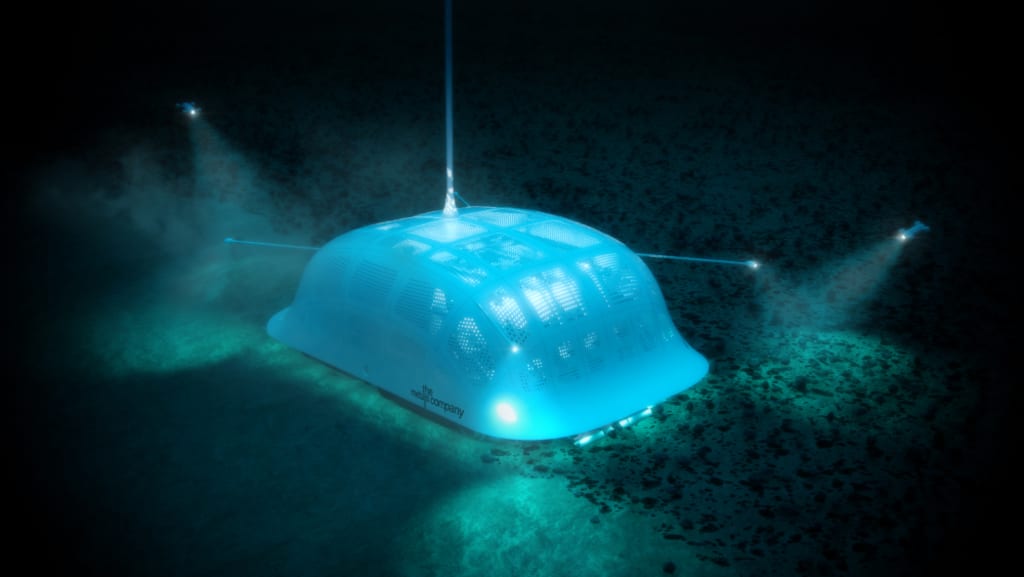

Since we wrote about these metal-rich "deep sea potatoes" in April, The Metals Company (TMC) has contacted us to see if we'd be interested in hearing how their study is progressing. We said "yes," and it appears that there is little disagreement over their practical value in the shift to a greener future.

According to TMC PR and Media Manager Rory Usher, "90% of the world's exploration contracts for nodules are in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, which represents less than half of 1% of the global seafloor." "However, this is the world's biggest source of manganese, nickel, and cobalt, dwarfing anything on land by several orders of magnitude. Two of the locations have enough metals on-site to meet the demands of 280 million automobiles, or every car in America and a fourth of the global fleet of vehicles.

Perhaps it's time to change course at a time when the value of Earth's ecosystem services could surpass carbon offsets in the struggle for our future. Although there are logistical and environmental challenges associated with deep sea mining, as a global network of researchers is learning, taking the risk could be worthwhile.

Is deep-sea mining just as harmful as mining on land?

Environmental manager at TMC Dr. Michael Clarke said, "I've been carrying out an environmental impact assessment like you would do for any mining project. After years of working on environmental impact assessments for terrestrial mines, I've now moved on to studying the impacts of mining the deep sea." The main distinction is that this one is located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, 4,000 meters (13,123 feet) below the surface, five days' sail from the closest port.

Because there is comparably less life in the benthos compared to terrestrial mining locations, this depth is significant in the search for manganese nodules. The abyssal bottom has 13 grams [0.46 ounces] of biomass per square meter, according to TMC, but Indonesian rainforests—one of the top nations for metal mining—has closer to 30 kilograms [66 pounds] of biomass per square meter.

Because forests, habitats, and ecosystems must be cleared in order to get metals from terrestrial sources, these areas become more susceptible to erosion and flow into the ocean. What about the seafloor? We already know that rainforests are hotspots for biodiversity and that they themselves serve as a carbon sequestration strategy.

Academics from a variety of institutions, including the Natural History Museum in London, the National Oceanographic Centre in Southampton, Heriot-Watt University in Scotland, the University of Leeds, the University of Bremen, the University of Hawaii, Texas A&M University, and the University of Maryland, have been studying life in the benthos to try and better understand this.

While there is life on and around the nodules, including some bigger species, they have found that the majority of it is minuscule. Early journalistic coverage of deep-sea mining has frequently used images of species from shallower waters to illustrate possible victims to warn of the likelihood of mass extinction events, but considering the already high cost of mining on land, it becomes a balancing act as to where the greatest harm rests. The bottom at 4,000 meters deep is misunderstood by a lot of people, according to Clarke. Without a doubt, there is life below, but it is not as plentiful as is sometimes suggested.

How can the impacts be determined?

Of course, just because something is modest doesn't mean it isn't significant. For this reason, TMC has been collecting baseline and collection data to determine the circumstances in the CCZ and potential effects of their method. These two datasets make up the two primary parts of an environmental impact assessment, and the International Seabed Authority regulator uses the findings to determine if the risks are tolerable.

Three years were spent on "our own baseline studies," according to Clarke, "and then we did the collector test, where we built a system that actually collects the nodules." "This was sent out toward the end of last year, and we gathered about 3,000 tonnes of nodules." The project's ultimate goal is to collect 1.3 million tonnes of nodules annually, thus the environmental impact insights gained from these studies will be tracked over time and scaled up to have a better understanding of how deep-sea mining in the CCZ will actually affect the ecosystem.

The main areas of concern center on the potential effects of the plume produced by the collectors, including the sediment released when the nodules are jettisoned from the seabed, the sediment released as they are filtered around, and the sediment that is dropped in the middle of the water when the nodules are transported to the surface. Although sediment may not seem very hazardous, there was fear that it may cause dust storms that could travel great distances and suffocate little species.

The feeding mechanisms of these species might potentially get clogged by these particles hundreds of square kilometers away from the source of the plumes, according to Clarke. "When we go out and do the testing, what we really discover is that the sediment enters the vehicle and exits the vehicle, generating what we refer to as a turbidity flow. It doesn't ascend much higher than 2 or 3 meters [6.6 to 9.8 feet] over the rear of the collector and acts more like a liquid than a gas. Consequently, it doesn't produce the substantial dispersive plumes that would be necessary for the sediment particles to cover hundreds of square kilometers and have an influence on species across a wide region.

The midwater plume may have had a similar effect, although testing have indicated that it is quite diluted. "You only have to get a few hundred meters away for it to dilute around 1,000 times and to become really hard to even find the sediment," added Clarke. Therefore, we don't believe there is much chance for these midwater sediment plumes to disperse across a wide area either. TMC is sure that they can limit the effects of deep-sea mining since these results have been confirmed in studies by MIT and Global Sea Mineral Resources.

About the Creator

Najmoos Sakib

Welcome to my writing sanctuary

I'm an article writer who enjoys telling compelling stories, sharing knowledge, and starting significant dialogues. Join me as we dig into the enormous reaches of human experience and the artistry of words.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.