The Echo Chamber

How We Became Prisoners of Our Own Opinions

We built them ourselves, brick by digital brick. We called them personalized feeds, curated content, and tailored news. We never imagined we were constructing the most sophisticated prisons in human history—ones that didn't require bars or guards because the inmates would never want to leave.

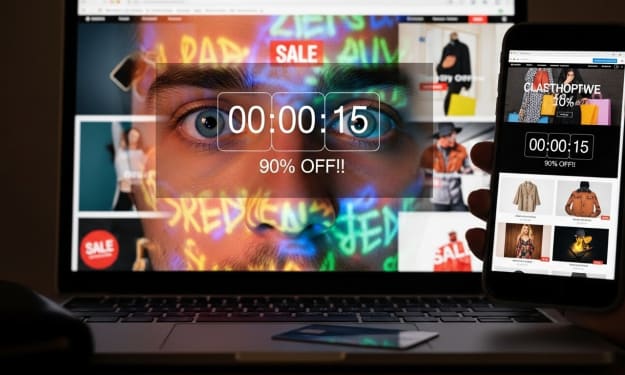

The architecture of our confinement is elegant in its simplicity. Every click, every like, every second spent watching tells the algorithm exactly what we want to see. It learns our preferences with terrifying efficiency, feeding us more of what we already believe and systematically eliminating anything that might challenge our worldview. We scroll through endless content, marveling at how everything we see makes perfect sense, never realizing we're looking at funhouse mirrors that only reflect distorted versions of ourselves back at us.

Dr. Aris Thorne discovered the phenomenon accidentally while studying social media behavior. He noticed something peculiar in his data: the more time people spent online, the more certain they became of their beliefs, yet the less able they were to articulate why they held them. Their knowledge became wider but shallower, their convictions stronger but their understanding weaker. They could recite talking points with religious fervor but collapsed when asked basic questions about opposing viewpoints.

"The human mind needs cognitive friction to stay sharp," Aris explained to his research team. "It requires the grit of contradictory evidence and the challenge of opposing perspectives to develop resilience. We've created an environment where thinking occurs on perfectly polished surfaces—no resistance, no challenge, just smooth, effortless sliding from one confirming piece of evidence to another."

The consequences manifested everywhere. Political discourse became two separate monologues shouted across an unbridgeable divide. Families fractured over versions of reality that bore little resemblance to each other. Public health measures became political statements, and scientific consensus became just another opinion.

Lena, a schoolteacher, watched it happen to her students. "They come to class already certain about everything," she told Aris during an interview. "When I present historical context that challenges their assumptions, they don't engage with it—they dismiss it as 'fake news' or 'propaganda.' It's not that they're rejecting the information; it's that their mental immune systems have become so overactive they attack anything foreign."

The most insidious part, Aris discovered, was that the echo chambers felt good. Being surrounded by people who shared your views, consuming media that confirmed your biases, watching algorithms serve you content that aligned perfectly with your worldview—it was psychologically comfortable. It produced a warm, self-affirming glow that made the messy, complicated reality outside seem harsh and unappealing.

"The chambers aren't just reflecting our preferences," Aris noted in his journal. "They're actively shaping them. They're not just giving us what we want—they're teaching us what to want."

His research took a darker turn when he began studying what happened when people attempted to leave their echo chambers. The results were alarming. Exposure to contradictory information didn't make people reconsider their views—it made them double down. The cognitive dissonance was so painful that their brains would perform remarkable feats of mental gymnastics to maintain their existing beliefs.

"The chambers are self-sealing," Aris realized with dread. "The more someone tries to escape, the tighter they close around them."

He designed an experiment he called "The Bridge." He recruited participants from opposite ends of the political spectrum and had them engage in structured dialogues using a platform that prevented their usual rhetorical patterns. They couldn't use buzzwords, couldn't employ us-versus-them language, and had to restate the other person's position to their satisfaction before presenting their own.

The initial results were promising. Participants reported increased understanding and decreased animosity. But when Aris followed up three months later, he found that 87% had returned to their original echo chambers, many with renewed vigor. The brief exposure to differing perspectives hadn't changed their minds—it had made them better armed to defend their own.

"The problem isn't just the chambers themselves," Aris concluded. "It's that we've lost the skills needed to navigate differences. We've forgotten how to listen, how to doubt ourselves productively, how to hold our convictions lightly enough to consider we might be wrong."

His final report contained a grim warning: "We have built a society where it's possible to go from birth to death without ever genuinely encountering a challenging idea. We've made disagreement so uncomfortable and confirmation so effortless that we're breeding a new kind of human—one who is certain about everything and understands nothing."

Yet in his conclusion, Aris found a sliver of hope. He discovered small communities—both online and offline—that deliberately cultivated intellectual diversity. They weren't echo chambers or debate chambers, but what he called "conversation chambers"—spaces where the goal wasn't to win or confirm, but to understand.

"The solution isn't to tear down the echo chambers," he wrote. "It's to build better rooms. Rooms with windows and doors. Rooms where we can hear not just echoes of ourselves, but the beautiful, complicated, sometimes uncomfortable symphony of human experience in all its diversity."

The work is slow, and the chambers remain largely intact. But in classrooms, community centers, and corner platforms of the internet, the bridges are being built—one conversation at a time.

About the Creator

The 9x Fawdi

Dark Science Of Society — welcome to The 9x Fawdi’s world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.