Scientists attempt to reverse human aging with a new approach

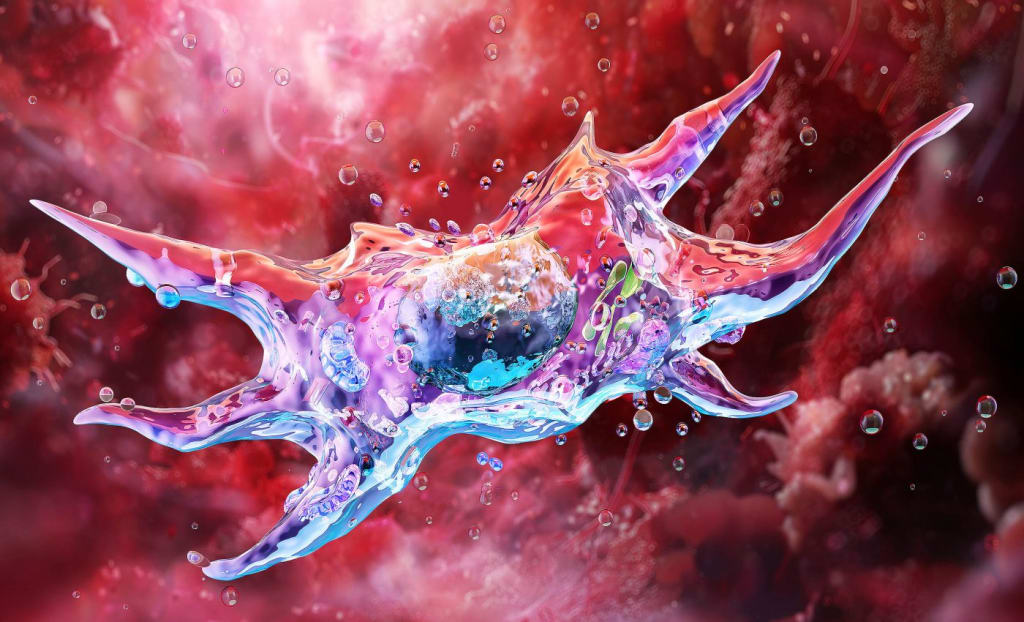

Scientists now see a way to push some cells back toward healthier roles, raising hopes for treating age-linked diseases.

Aging rewires the jobs your cells do, and that slow transformation can result in scarring, weakness, and organ failure.

Across the body, tissues stay functional because each cell keeps a clear identity and follows the instructions embedded in its genetic material.

At Altos Labs, researchers tracked how aging blurred those instructions across many organs and cell types.

The work was led by Dr. Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, Ph.D., who studies cell reprogramming and tissue repair. By focusing on identity loss, the team treated aging less like wear and tear and more like bad instructions.

Aging cells drift toward scarring

One paper compared gene activity patterns in samples from aging individuals, then found the same push happening in many diseases.

Mesenchymal drift showed up in cells that should have stayed tightly specialized.

Cells turned on genes linked to flexible support tissue, and that change can thicken organs and slow healing.

Because the signal appeared in so many places at once, researchers began thinking about aging as a systemic problem.

Mesenchymal drift and disease

The mesenchymal drift was not a rare quirk of one organ, since it rose in illnesses that scar or inflame tissue. Higher levels matched disease progression and lower survival, which made the pattern hard to ignore in medical data.

That link held across more than 40 human tissue types and 20 different diseases, including kidney failure and lung scarring.

Because the authors worked within one company, independent groups will need to confirm where the drift truly predicts outcomes.

Aging cells lose control

To test whether the drift was a driver of harm, researchers silenced a few master gene controllers tied to the scar program.

Cells then regained epigenetic marks, chemical tags that steer genes on or off, that looked more like youth.

That response suggested the drift was not just damage, since changing a few switches altered many downstream genes.

Even so, the experiment stayed in controlled settings, and real organs add immune signals, hormones, and messy timing.

Resetting aging cells

Another approach aimed to rewind cells without wiping their memories, since tissues fall apart when too many cells reset.

This partial reprogramming, brief activation of gene-resetting factors, reduced mesenchymal drift before cells started acting like stem cells.

A major review described how full reprogramming erases cell identity, so the safer window became the goal.

By catching benefits before cells went blank, the work pointed toward treatments that reset aging signals while keeping structure intact.

Clues from earlier mice

Earlier animal work had already shown that short bursts of the same gene program could change aging-related biology.

In one experiment, repeated pulses improved aging markers and extended life in a mouse model of rapid aging.

A later study used longer regimens in normal mice and reported younger molecular patterns in kidney and skin.

Those results built confidence that careful dosing can help, but they also showed how easy it is to overdo reprogramming.

Reprogramming mesenchymal drift

Reprogramming remains difficult to control, because the same changes that refresh cells can also push them toward chaos.

If too many cells lose their identity at once, tissues can malfunction, and unchecked division raises the risk of cancer.

Developers must also solve delivery, since gene therapies have to reach the right cells and switch off on time.

“Restoring and maintaining cellular health is one of the most ambitious and important challenges of our time,” said Dr. Belmonte.

Trials to reverse aging in cells

When researchers start testing in people, they often choose organs where doctors can deliver small doses and watch effects closely.

A registered trial planned a single dose of ER-100 for glaucoma and certain optic nerve injuries.

That choice made sense because eye injections can stay local, and vision tests can detect subtle changes over months.

Even with a clean safety record, moving from the eye to whole-body treatment will demand stronger control and longer follow-up.

Aging cells and mesenchymal drift

If mesenchymal drift is a common aging pattern, reversing it could reduce scarring and keep organs working healthily for longer.

“The cause of many diseases, including the ones that are age-associated, is the deterioration of cellular health,” said Belmonte.

This new drift framework gave researchers a concrete target, and it may guide drugs that quieten scar programs instead.

No single reset will stop aging, but mapping one shared process may help doctors treat several diseases with one strategy.

Together, these studies tied a measurable drift in cell behavior to aging, then showed ways to dial it back.

The next steps will hinge on safe delivery and independent replication, since any therapy that rewrites cell programs carries inherent risks.

The study is published in The National Library of Medicine.

About the Creator

Adrian Villellas

Ingeniero informático, emprendedor en marketing digital y ad tech y divulgador y colaborador en iniciativas de investigación científica. Earth.com Okdiario.com programaticaly.com ecoticias.com ecoticias.com/hoyeco y ecoticias.com/en

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.