"Revealing the Mysteries of Mars: Its Partially Molten Iron Core"

"Exploring the Heart of the Red Planet's Geology and Magnetic Field"

If the explorers from Journey to the Center of the Earth were to venture to the center of Mars instead, they would not encounter the subterranean oceans or live dinosaurs they came across in the movie. However, it is likely that they would observe a distinct composition in comparison to Earth's core. Earth possesses a mantle composed of rock that exhibits sluggish liquid-like movements. Below the mantle lies a liquid iron outer core and a solid iron inner core. Considering that both Earth and Mars are rocky planets and may have experienced similar surface conditions in the distant past, it might be tempting to anticipate a comparable interior on Mars. Nevertheless, this assumption is not entirely accurate.

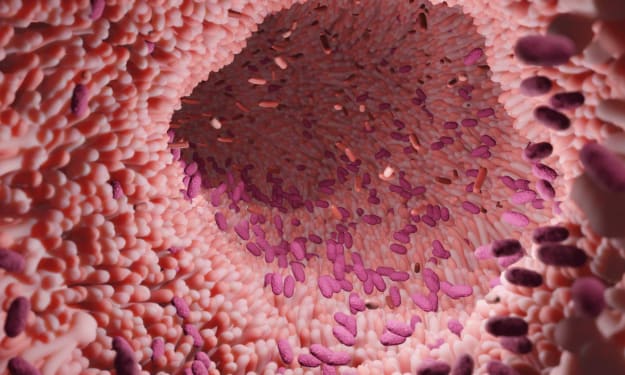

When utilizing data from NASA's InSight lander and other spacecraft, two teams of researchers endeavored to closely examine the core of Mars within a laboratory setting. Their findings revealed that the internal composition of the red planet differs significantly from that of Earth. Previous data obtained from NASA's InSight lander's SEIS (Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure) project had suggested the presence of a sizable yet low-density core on Mars. However, through a comprehensive analysis incorporating additional seismic signals, it has been determined that the supposed surface of the Martian core is, in fact, a substantial layer of molten rock. Consequently, the actual core of Mars is presumed to be considerably smaller in size.

To understand why the previous InSight measurements yielded a core estimate that was both too large and not heavy enough, it is necessary to trace back to the formation of Mars. Initially, it was believed that Mars was initially covered by a massive magma ocean that eventually transformed into a diverse mantle consisting of silicates, iron, and radioactive elements that generated heat. InSight's seismic data corroborated this theory. The low core density proposed based on the lander's observations indicated that there must be a significant amount of light elements such as silicon, carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen in the core. This hypothesis appeared reasonable since the Martian core was previously assumed to have formed before the dispersion of all the gas that our Solar System was born in.

Geophysicist Amir Khan of ETH Zürich, who headed one of the research teams in a study published in Nature, stated that there is a lack of understanding regarding the identity and abundance of the primary light elements in the Martian core.

Both Khan and Henri Samuel, who led another team in a study also published in Nature, now believe that the mantle of Mars is homogeneous rather than heterogeneous. They have found that the physical properties of the mantle are consistent throughout. In contrast, Earth's mantle is predominantly heterogeneous.

In a previous discovery, InSight detected a marsquake caused by a meteorite impact. Samuel's team discovered that the seismic waves that traveled through the planet could not be explained by a heterogeneous mantle, as this would have resulted in slower wave velocity.

Both research teams supported these findings by conducting computer simulations and models to understand how these waves propagate deep within Mars. These simulations further revealed that the seismic wave velocity observed during the marsquake could only be achieved if Mars had a small, dense core of liquid iron surrounded by a molten silicate layer. If the core had been less dense, the waves would have traveled at a faster pace. Additionally, both teams compared the density of liquid iron to the composition of elements believed to make up the surface of the core. They found that liquid iron was significantly denser than what InSight's measurements had previously suggested.

Therefore, what was initially thought to be the surface of the Martian core is now understood to be a separate layer, approximately 1,780–1,840 km (1,106–1,143 mi) in thickness. The actual core is now believed to be much smaller and denser, primarily consisting of molten iron with possible traces of other elements.

The examination of the red planet in this virtual dissection has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of the development of rocky planets, including our own. Additionally, it has the potential to provide insights into the loss of Mars' magnetic field approximately 4 billion years ago. It is plausible that the excessive heat retained by the core hindered the maintenance of a magnetic dynamo.

According to Samuel and his colleagues, the generation of a magnetic field through a thermally driven dynamo action necessitates efficient convective motion within the metallic core, which implies the loss of core heat. However, certain processes have impeded the cooling of the core.

While there are still uncertainties, both Khan and Samuel concur that further investigation is required in the future. Nevertheless, we are finally gaining a true understanding of the fundamental nature of Mars at its core.

Comments (1)

Nice article. I enjoyed it. Keep it up.