Photographing Black Holes

First Photographed Black Hole

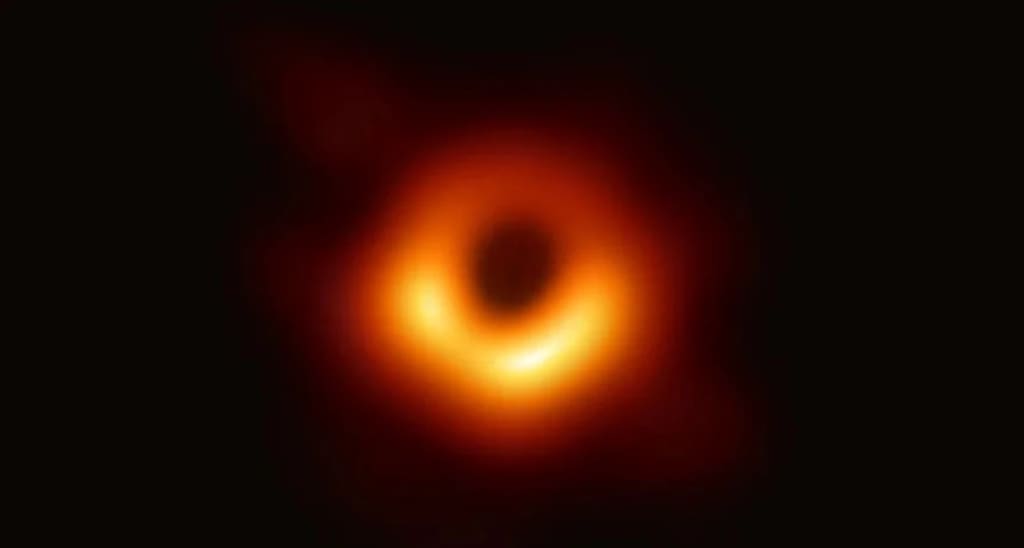

A development that took place about 4 years ago deeply affected all branches of science, especially physics and astronomy. On April 10, 2019, it was announced that a black hole image was taken for the first time in human history! More specifically, the image of the high-mass black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy in the constellation Virgo has been released after 2 years of painstaking work. The image was taken in 2017 by a system called the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), which was created jointly by radio telescopes located in different corners of the Earth. The image created the agenda the day it was published, and there are very valid reasons for this.

The Importance of This Observation

Black holes are high-mass celestial bodies that are predicted by Einstein's general theory of relativity and attract everything around them, including light, in an irresistible way. The general theory of relativity is widely accepted among physicists because it has been independently verified many times. It is only natural that the predictions of such a widely accepted theory should be taken seriously.

But no matter how solid the theory that put forward the prediction is, it is always vital for scientists to confirm the predictions. The effect of black holes on the objects around them has also been observed in the past years, but taking the image of the black hole directly is an observation that will overshadow other observations. We can safely say that this observation strengthens the position of the general theory of relativity in the scientific community, which is already solid.

So, would you like to observe celestial bodies those found in space? There is a great product that I can recommend for this, if you are interested in astronomy, you can click on the link below and buy it. Thanks to this product, you can observe the place as your heart desires and witness how wonderful this vast place is.

How Did We Succeed Despite These?

In fact, no powerful telescope would be able to detect it without the "glowing" material called the accretion disk around M87's central black hole. The accretion disk consists of matter caught in the gravitational pull of the black hole, and this material revolves around the black hole at very high speeds. Matter spinning at high speeds rubs against each other and heats up and emits electromagnetic radiation (via blackbody radiation). In fact, accretion disks are not just structures that form around black holes. Clouds of this substance are also found around stars. The wavelength of the radiation emitted from the accretion disk depends on how hot this material is.

The black hole swallows all the light around it. In other words, no matter how strong the radiation around the black hole is, the region within a boundary called the "event horizon" appears completely dark. If we see a dark "circle" in the middle of the accretion disk, we can safely say that it is a black hole. This is exactly what the EHT team managed to visualize.

Obtaining such a high resolution image is not a task to be done with a single radio telescope. Our current technology is not advanced enough to make a radio telescope with such a clear aperture that it can take such a detailed picture on its own. So the scientists came up with an interesting solution: combining data from multiple telescopes and analyzing that data as if it came from a single radio telescope. For this, they process the data of radio telescopes located in different corners of the Earth with a very precise synchronization, and as a result, much higher resolution images are obtained. We mentioned that the data was collected in 2017. The reason why it takes so long to process the image is that this data synchronization process is very difficult. Katie Bouman, a 29-year-old postdoctoral researcher who designed a significant part of the code that carries out this process, contributed greatly to the successful completion of this challenging process.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.