Melting Antarctic Ice Did the Opposite of What Scientists Expected

Why the Southern Ocean Might Not Help Us Fight Climate Change After All

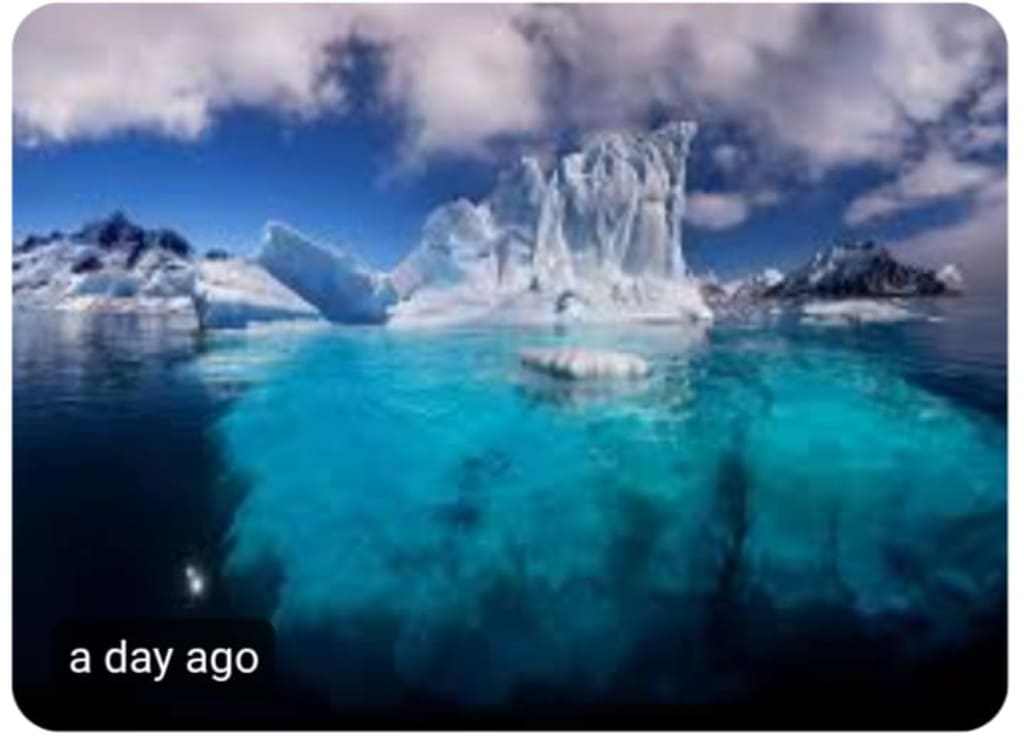

Antarctica’s ice sheets are melting faster than ever. For decades, scientists believed this could actually help slow climate change by feeding the ocean with iron, a nutrient that powers algae growth — and in turn, draws carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

But recent research has turned this idea on its head. The reality, it turns out, is far more complicated — and worrying.

What Scientists Thought Would Happen

In the Southern Ocean, iron is scarce. Phytoplankton, the tiny ocean plants that form the base of the marine food web, can’t grow without it. The theory was simple:

More melting ice → more iron → more algae → more carbon absorbed from the atmosphere.

It made sense — and it seemed like a natural climate “safety valve.” Scientists even thought that icebergs, scraping up the bedrock beneath Antarctica, could be delivering this iron to the ocean.

The Surprising Findings

A team of researchers analyzed ocean sediments that date back hundreds of thousands of years. These sediments record past periods when West Antarctica’s ice sheets melted massively.

The expectation? Massive algae blooms. The reality? Almost nothing.

The reason: the iron in melting icebergs wasn’t in a form algae could use. It was chemically “locked up” and barely soluble in seawater. More iron didn’t mean more food for phytoplankton.

“Normally, an increased supply of iron in the Southern Ocean would stimulate algae growth,” said lead author Torben Struve. “But in this case, it simply didn’t happen.”

Why the Iron Didn’t Work

The chemistry behind it is fascinating. Icebergs grind up some of the oldest, most weathered rocks on Earth. The iron in these rocks is chemically different from dust-borne iron that usually fertilizes oceans.

Dust iron — blown from continents — dissolves easily and is perfect for algae. Iceberg iron? Not so much. Most of it remains locked in the sediment, useless to the tiny plants that normally pull carbon out of the atmosphere.

Implications for Climate Change

This discovery has serious implications for our climate future. If melting Antarctic ice doesn’t feed algae as expected, the Southern Ocean may not be able to absorb as much carbon dioxide. That means more greenhouse gases remain in the atmosphere — and global warming could accelerate.

Scientists call this a positive feedback loop: instead of slowing climate change, the process might actually speed it up.

“What matters is not just how much iron enters the ocean, but the chemical form it takes,” explains co-author Gisela Winckler. “This fundamentally alters how we think about carbon uptake in the Southern Ocean.”

Lessons from the Past

Sediment records also show what happened during previous warm periods: the ice sheets melted, icebergs flooded the ocean, and yet the boost in algae never came.

Fast forward to today — glaciers in West Antarctica are thinning rapidly. The so-called “Doomsday Glacier” is retreating, icebergs are breaking off more frequently, and the same pattern could be repeating — only this time under human-driven climate change.

The Bigger Picture

The key takeaway? Earth’s climate system is full of surprises. Even seemingly straightforward effects — like melting ice delivering nutrients to the ocean — can backfire. The Southern Ocean, one of our planet’s natural “carbon sinks,” may be less reliable than scientists once thought.

This research reminds us that climate change is complex, and nature doesn’t always follow our expectations. Solutions may be trickier than they appear, and adaptation strategies need to account for these unexpected feedbacks.

Bottom Line

Melting Antarctic ice releases iron into the ocean, but most of it is unusable by algae.

Expected carbon dioxide absorption by the Southern Ocean might not happen.

This counterintuitive effect could make global warming worse than current models predict.

Understanding the chemical form of iron is critical for predicting future climate feedbacks.

Antarctica is teaching scientists a hard lesson: in nature, things are rarely as simple as they seem. Sometimes, the ice doesn’t just melt — itsurprises us.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.