El Paso Police Department

Selective Enforcement, Double Standards, and the Erosion of Trust

This article is not about Stephenie Han. It is about the El Paso Police Department (EPPD) and a growing perception among its officers that rules, ethics, and discipline are applied selectively — favoring some while punishing others — and that this inconsistency is crushing morale.

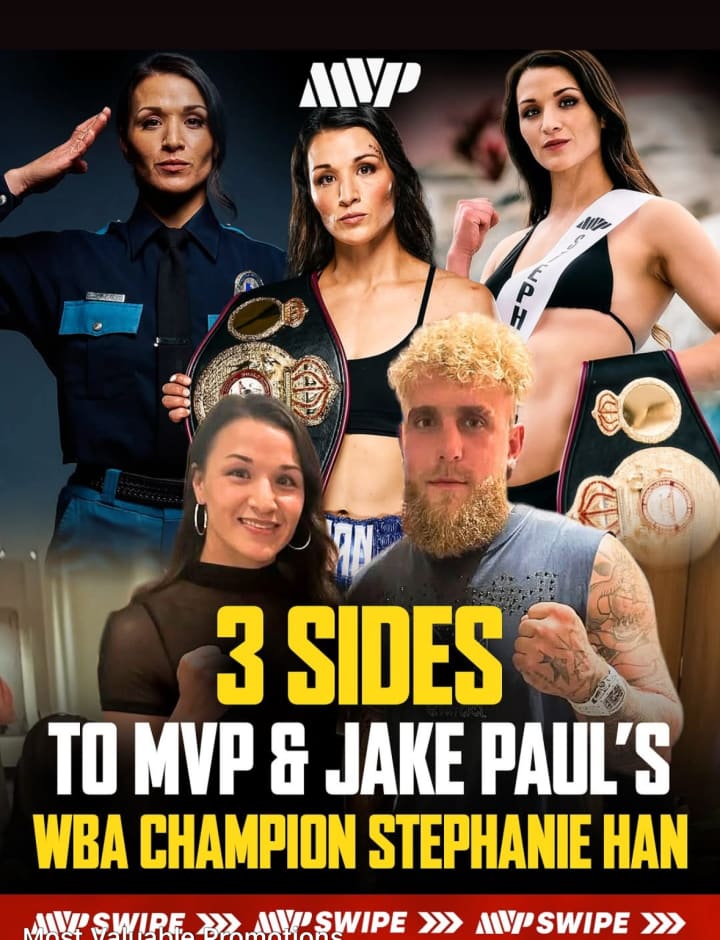

Everyone in El Paso knows who Stephenie Han is: an undefeated professional boxer, a mother, a current WBA Lightweight Champion (KO victory in February 2025), and an active EPPD officer. She is scheduled to defend her title against Holly Holm in January 2026. Recently she signed a promotional deal with Most Valuable Promotions (MVP), the company co-founded by Jake Paul, and continues to train with longtime coach Louie Burke.

The trouble begins with the way her new promotional campaign is being presented — and how the department appears to look the other way.

“Have you seen the billboard of her, where it looks like she is promoting a criminal lawyer,” asks an officer with the El Paso Police Department who asked we not publish her name. “We can’t recommend a defense attorney or a bond company, but there she is, on a billboard, looking like she is recommending an attorney.”

“What we need to focus on is that everyone knows she’s a cop,” says one officer from the El Paso Police Academy. “Might not be the best cop, but she does wear the badge. I know if I was on a billboard for something I would be in front of IA. But not Han.”

Other promotional graphics are more explicit. One widely circulated image, apparently created by MVP, shows Jake Paul in the foreground while a large photo of Han in full EPPD uniform — including department patches — appears in the background.

“This thing, who approved it,” asks another officer with the El Paso Police Department. “Was it Gomez at the PIOs, was it the Chief? I got friends who are into other sports, why can’t the department give them the same sort of leeway they seem to be giving her?”

Officers point to recent history for contrast. When Officer Andrea Zendejas was discovered operating an OnlyFans account on her own time, off-duty, she faced intense departmental scrutiny and criticism. Yet Han’s high-profile commercial endorsements — even those that blur the line between her role as a police officer and her role as a sponsored athlete — appear to sail through without consequence.

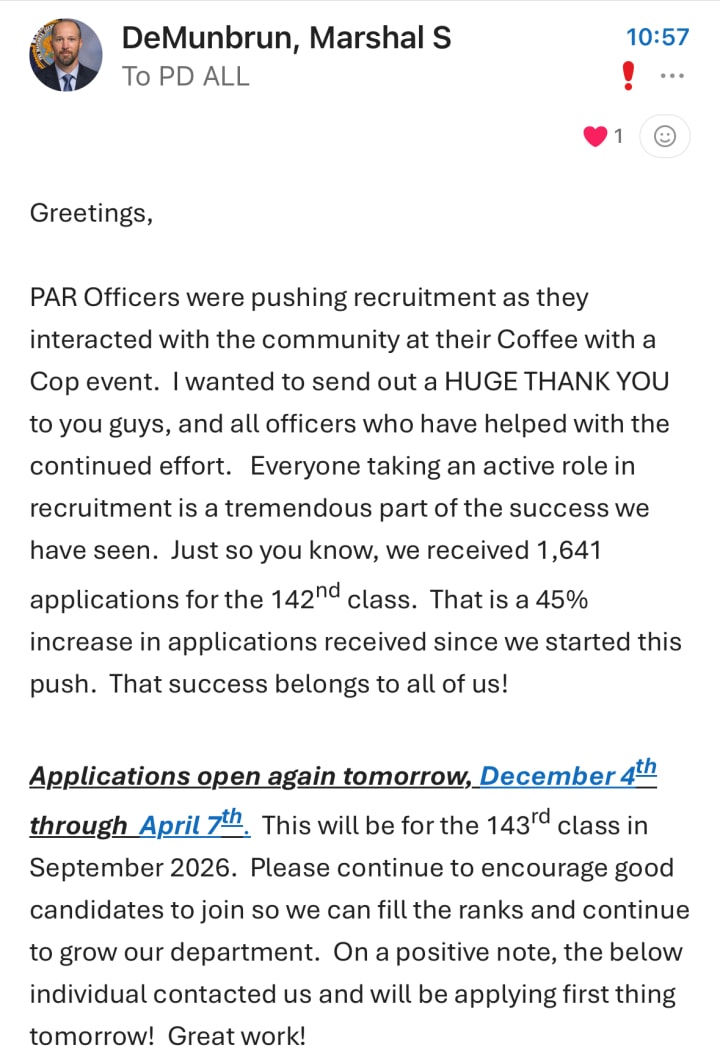

“That is garbage,” says another officer. “[Andrea] Zendejas has an OnlyFans and she was doing that when she was off duty. The department gave her a lot of flack over it. Pressure one and praise the other one. I’m sure DeMunbrun is going to say that 45% jump in applications is because of Han.”

Why even the appearance of a conflict of interest is poisonous for law enforcement

Police officers occupy a unique position of public trust. Citizens must believe — without hesitation — that the officer standing in front of them is impartial, that their badge represents fairness under the law, not personal profit or side deals.

When an officer’s image is used (even passively) in advertising alongside criminal-defense attorneys, bail bondsmen, or any service that exists on the other side of an arrest, it creates at least the perception that the police department and the criminal-justice defense bar are commercially intertwined. That perception, whether fair or not, undermines the entire system.

“I arrest someone and when we are driving to the NERCC, let’s say the 15 (a person who has been arrested) asks me for the dame of a lawyer who can help him,” says another patrol officer. “I recommend someone and the guy hires that lawyer and ends up with 10–20 years in prison. On appeal the guy tells his new lawyer that the cop who arrested him said to hire the other lawyer. You can bet I would buy hours for that. Why is this different?”

The officer’s point is simple but devastating: if rank-and-file cops would face Internal Affairs investigations, suspension, or termination for far less overt conflicts, allowing one officer’s likeness to appear in such advertising — without clear, public rebuke — signals that the rules bend for the famous or well-connected. That message travels fast inside a department and even faster into the community.

“She [Han] is a liability in that she is allowed to do things other officers in the department are not,” says a senior officer with EPPD. “She can appear on the cover of a city-wide magazine, with an EPPD patch on her shorts, and they [EPPD] see it as promotion. I wear a tee shirt that has an image they deem violent on it, and it’s an issue. Why is this our reality?”

“What if she is injured in this fight, and must take extended leave to recover,” asks the same officer. “She’s out of the game, as it were. We’re told not to do anything, when we are off duty, that may render us unfit for full duty, but she can fight?”

The bigger picture

While command staff publicly celebrates Han as a recruiting asset, many line officers see something else: a department that preaches uniformity and impartiality yet practices favoritism. Rules are not applied evenly. Transparency is selective. Off-duty conduct that brings positive attention to the department is praised; off-duty conduct that brings any controversy is crushed.

Officers are angry — and morale is suffering — because they know the public ultimately judges the entire agency by the lowest standard it is willing to tolerate. When even the hint of a conflict of interest is ignored for one officer, every officer’s credibility takes a hit.

Something needs to change. Policies must be enforced consistently, transparently, and without regard to fame, boxing records, or recruitment statistics. Until that happens, the El Paso Police Department will continue to struggle with the one thing no agency can afford to lose: the trust of the people who wear the badge and the citizens they swore to serve.

To many officers, the department’s actions feel incomprehensible and hypocritical. Rules that are rigidly enforced against one cop evaporate when another brings positive headlines. Transparency is treated like an optional slogan: Command nods at it in press releases, then walks right past it in practice. While leadership eagerly showcases Stephenie Han as the reason for a reported 45% surge in applications and parades her success as proof of a thriving agency, far less publicity is given to incidents that cast a darker shadow. For example, Officer Robert Seelig from the Central Regional Command was arrested for DWI by the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office — an off-duty incident that drew no press conference, no press release. The silence is deafening, and to the rank-and-file it sends a clear message: good news gets amplified when it serves recruitment, bad news gets buried when it doesn’t. That selective narrative only deepens the resentment and the growing belief that fairness inside the El Paso Police Department depends entirely on whose story makes the department look better.

Let's hope the second floor [Command] comes to their collective senses soon.

About the Creator

Steven Zimmerman

Reporter and photojounalist. I cover the Catholic Church, police departments, and human interest.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.