Don’t Ask. Don’t Tell. Until Someone Lives To Tell.

The Web Thrives on Silence-Perfect 10 Pathways Beneath the Flight Lines.

By an independent investigative researcher

⸻

A note to the reader

This article relies exclusively on public records, court filings, sworn testimony, and contemporaneous reporting. It does not allege criminal coordination beyond what has been established in court. Its purpose is to examine patterns, parallels, and institutional blind spots that emerge when timelines are placed side by side. Patterns are not accusations. But patterns ignored become policy.

⸻

A trafficker with roots, reach, and infrastructure

Federal court records establish Ronald R. Eppinger as a central operator in a multi-year sex-trafficking enterprise dismantled in 2001. Investigators documented that women were trafficked into the United States from the Czech Republic, among other locations, and exploited through escort services, nightclub-adjacent businesses, and “modeling” fronts concentrated in Florida’s major port cities.

Less frequently discussed is how Eppinger was positioned to operate at scale.

Public records show that Eppinger was born in Massachusetts, a state with long-established organized-crime investigations and federal court infrastructure. FBI documents later referenced Eppinger’s own statements describing his role as a “finder of women,” his use of nightclubs as access points, and his associations with individuals identified by law enforcement as connected to the Genovese crime family. This article does not allege membership; it reports that such associations appear in investigative files, a distinction that matters.

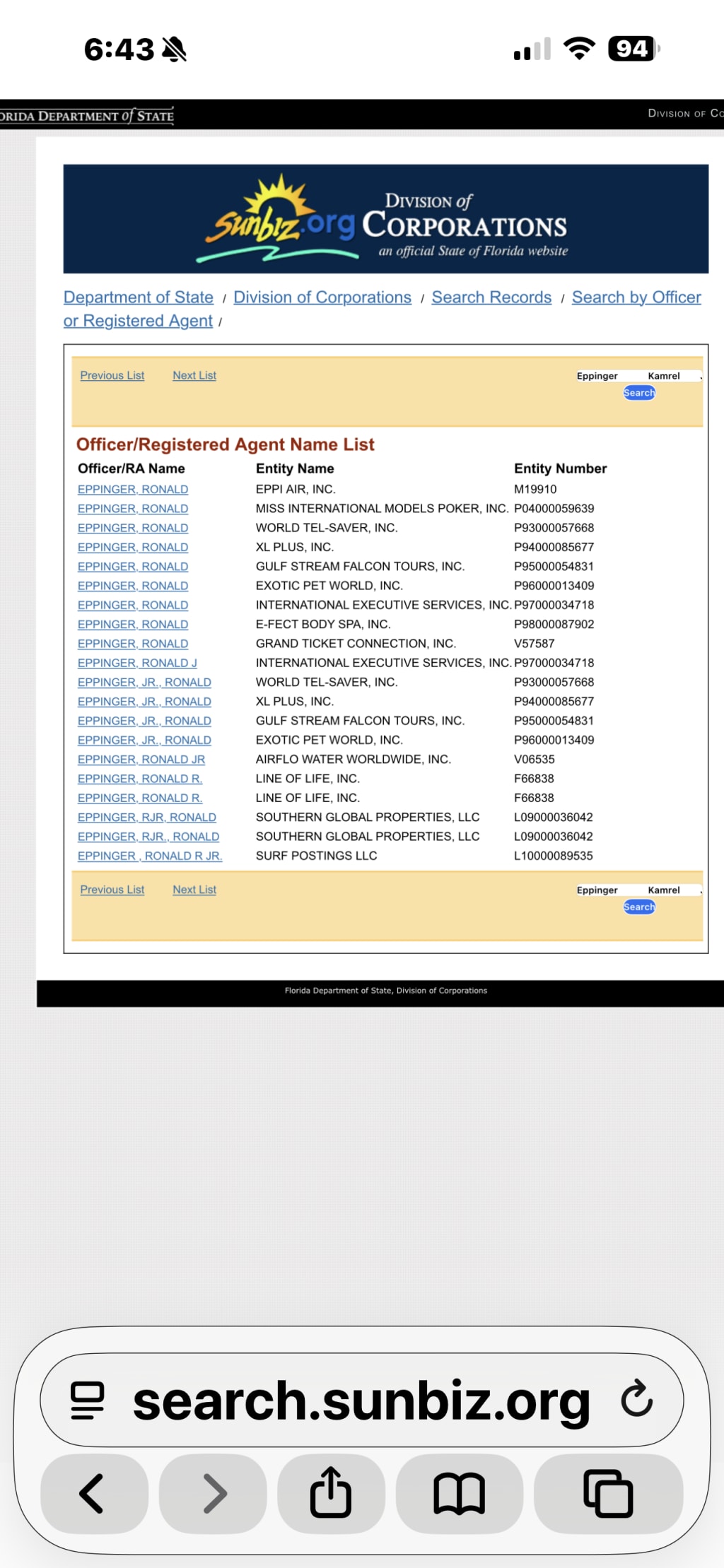

Equally important is Eppinger’s business footprint. Florida records and contemporaneous reporting place him behind or associated with:

• Airline-related LLCs and aviation-adjacent entities

• Extensive real-estate holdings across South Florida, Volusia County (including Pierson), and central Florida

• A dense web of short-lived corporations tied to entertainment, escorting, travel, and “international services”

These are not incidental details. Trafficking at scale requires transport, property, capital, and cover. Eppinger had all four.

⸻

Parallels that deserve scrutiny, not silence

The structure of Eppinger’s operation bears notable resemblance to that later exposed in the case of Jeffrey Epstein. This comparison is not moral shorthand; it is structural.

Both models, as documented in court records and investigative reporting, relied on:

• Layered corporate entities that obscured ownership and liability

• Real estate used as sites of recruitment, exploitation, or control

• Transportation access — aviation, ports, and interstate corridors

• Women recruited or coerced into facilitating abuse, often framed as assistants, recruiters, or intermediaries

These similarities matter because they illustrate repeatable methods, not unique villains.

A direct connective fact exists as well. In sworn testimony, Virginia Giuffre stated that when she mentioned Ron Eppinger to Epstein, Epstein indicated that he already knew, or knew of, Eppinger. That statement does not prove collaboration. It establishes prior awareness — a data point that belongs in the public record.

⸻

The women who disappear from the narrative

Public attention tends to crystallize around male financiers and operators. Far less attention is paid to the women embedded within trafficking networks, even when they are named in court documents.

In Eppinger’s case, two female co-defendants were listed in his arrest and conviction, yet their roles and trajectories remain largely unexamined in public discourse. This pattern is familiar. In the Epstein case, women connected to the operation were rarely scrutinized until Ghislaine Maxwell was charged — and even then, discussion often narrowed to a single figure.

This selective visibility matters. Networks persist not only because of powerful men, but because gendered assumptions allow certain roles — recruiter, gatekeeper, scheduler, handler — to remain unexamined. Silence protects systems.

⸻

Florida corridors and Arkansas echoes

Eppinger’s Florida footprint intersects geographically and temporally with another set of unresolved American questions: the legacy of Mena, Arkansas, and the Iran-Contra era. During the same decades that trafficking enterprises expanded along Florida’s port cities, Arkansas businessman Dan Lasater operated a drug-distribution network later adjudicated in federal court.

Lasater is relevant here for two documented reasons. First, he maintained significant real-estate holdings in Florida, including areas overlapping with corridors where Eppinger operated. Second, Lasater’s publicly acknowledged relationship with Roger Clinton — which resulted in Roger Clinton’s own conviction — places these activities within a politically sensitive historical context.

Again, overlap is not proof of coordination. But real-estate convergence in the same regions, during the same period, across different criminal economies, raises legitimate questions about why Florida — and certain counties within it — repeatedly function as safe harbors for exploitation.

⸻

Justice reform, profit, and unintended incentives

While trafficking and drug-distribution cases moved slowly through the courts, South Florida was simultaneously becoming a testing ground for criminal-justice reform. The modern drug court model emerged with the stated goal of diverting non-violent offenders into treatment. In many cases, it succeeded.

But drug courts also created new profit centers: treatment providers, compliance monitoring, testing services, bond services, and process-serving operations. Public records show that Tony Rodham engaged in Florida-based business ventures tied to process serving and bond-related services during this era. His brother, Hugh Rodham, an attorney, later became involved in advocacy and advisory roles connected to drug-court expansion.

None of this is illegal. But it underscores a recurring theme: systems designed to manage harm can also monetize it. When oversight fragments, incentives matter more than intentions.

⸻

From bodies to balance sheets

Sex trafficking is not the only form of exploitation that thrived in these same decades. Investigations into prison blood-plasma programs — including those linked to Arkansas’s Cummins Unit — exposed how incarcerated populations were used as biological resources in a multi-state, international supply chain.

Different victims. Different mechanisms. Same outcome: human vulnerability converted into revenue through institutional design.

⸻

A working theory, not a verdict

A reasonable working theory, grounded in public records, is this:

Certain American corridors — combining transportation access, real estate, fragmented jurisdiction, and privatized services — repeatedly generate conditions where exploitation can scale, persist, and evade accountability, even without centralized coordination.

This theory does not require conspiracies. It requires silence, compartmentalization, and time.

⸻

Why living witnesses matter

Survivors like Virginia Giuffre matter because they collapse compartments. When testimony connects names that paperwork kept separate, it forces institutions — and the public — to confront what was hidden in plain sight.

“Don’t ask, don’t tell” is not just a cultural phrase. It is an operating condition. And it fails the moment someone lives to tell.

⸻

Conclusion: asking the whole question

This article does not ask readers to accept a single narrative. It asks them to look at the full timeline. To notice when the same places, methods, and blind spots recur across different scandals. To ask why women embedded in networks are so often erased from the story. And to question systems that profit from silence.

Oversight is not optional in a democracy. It is cumulative.

The web thrives on silence. It weakens when connections are finally named.

⸻

Editorial note

This article relies on public records, sworn testimony, court filings, and contemporaneous reporting. It does not allege criminal conduct beyond what has been adjudicated. Its aim is to examine structural overlap and institutional accountability, not to assign guilt by association.

About the Creator

SunshineChristina

I am a social and criminal justice reform advocate and researcher. I love true crime and also fighting to help bring and spread awareness to the myriad of troubling issues that are effecting American society.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.