Beyond the Iron Curtain

How a teenage encounter with three American boys, a pristine Persian carpet, and a National Geographic atlas planted seeds that would bloom thirty-five years later at one of the world's most famous waterfalls.

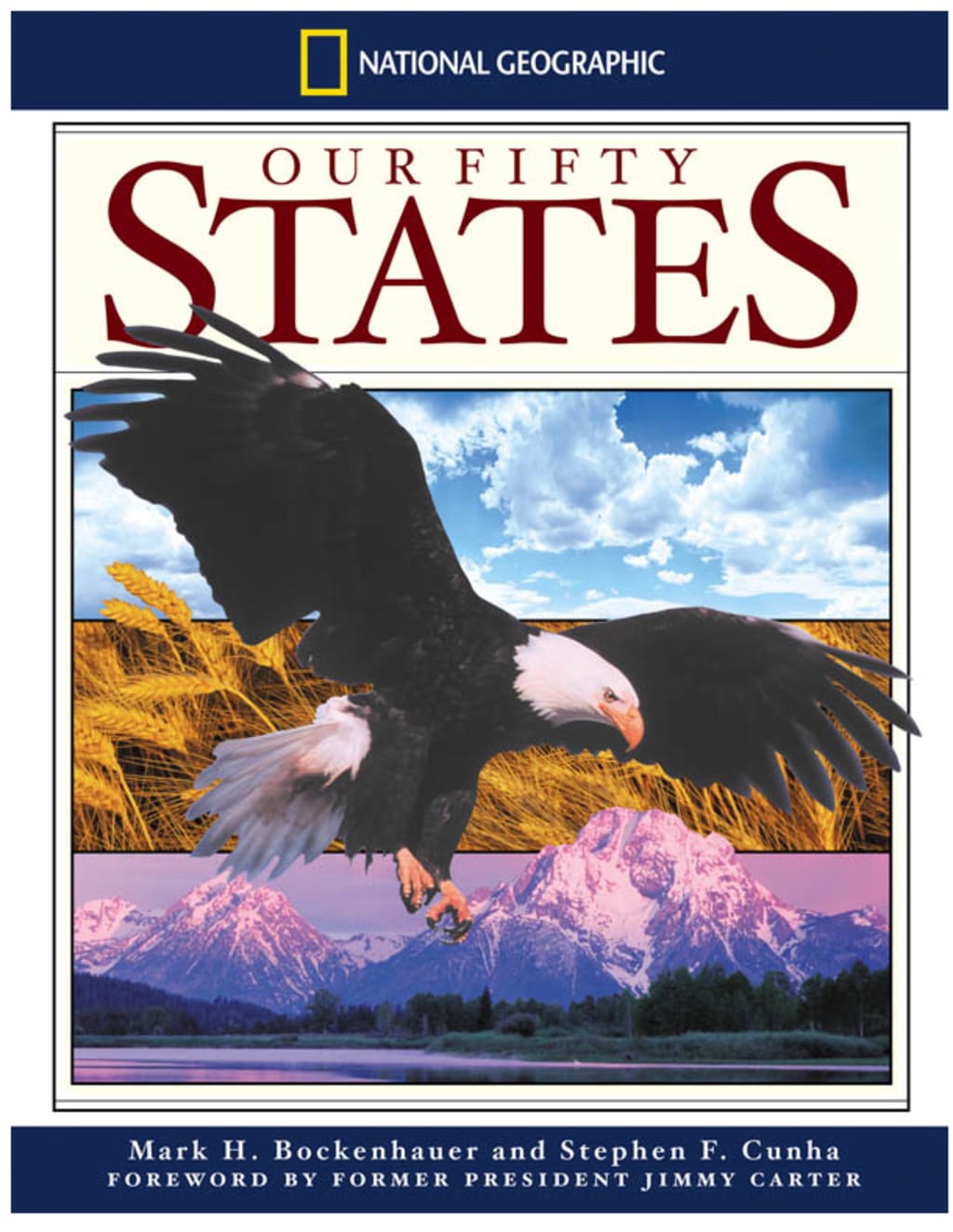

My National Geographic Picture Atlas of Our Fifty States

The year was 1986, and I was drowning in the intoxicating currents of Gorbachev's winds of change. At sixteen, armed with a fountain pen and delusions of literary grandeur, I had already published several pieces in local and national press. My parents—two engineers who had transformed our apartment into a miniature Library of Alexandria—watched with bemused pride as their only child scribbled verses between math equations and dreamed of conquering the world through journalism.

Those were electric times in the Soviet Union. Perestroika had cracked open a door that had been welded shut for decades, and through that crack, the Western world began to seep in like water through a dam. American authors found talented Russian translators faster than you could say "glasnost." Television discussions grew heated enough to fog up apartment windows across eleven time zones. Underground musicians literally took to the Moscow underground, turning subway passages into concert halls where Scorpions' songs became our generational anthems.

We all felt it—that famous wind of change the German rockers sang about. It was as if someone had finally opened the windows in a stuffy room, and we were all taking our first deep breaths of fresh air.

The Summons

It was during this heady period that I found myself summoned to the principal's office along with several other students. Now, in the Soviet Union, being called to the principal's office could mean anything from receiving a commendation for academic excellence to being expelled for reading banned literature. The range of possibilities was broad enough to make your palms sweat.

"You know, guys," our principal began, his eyes twinkling with the kind of excitement usually reserved for announcing extended summer holidays,

"you are lucky to be selected by our committee to represent our school."

My heart did a small leap. This sounded promising.

"A group of American students is about to arrive to visit our country, our city, and our school."

American students. Real, live Americans. Not the caricatures from our textbooks or the shadowy figures in our propaganda films, but actual teenagers from across the ocean. The implications were staggering.

The principal handed us a manila folder thick enough to choke a bear.

"Please read the detailed instructions that we have carefully prepared for you. It mentions how to behave, what to ask, and what to answer. Moreover, it contains a detailed description of American slang and typical public behavior."

I flipped through the folder later that evening. It read like a field guide to an alien species. Americans shake hands firmly. Americans smile frequently, even at strangers. Americans say "How are you?" but don't actually expect a detailed answer about your health, family troubles, or philosophical worldview.

The most surreal part came next: special coupons to purchase products not available in regular Soviet supermarkets but essential for our dinner tables during the visit.

"No one should pay attention to the fact that there is a deficit in the Soviet Union," the instructions read with the kind of bureaucratic doublespeak that would make Orwell weep.

The Great Preparation

I had one month to prepare for this cultural collision, and I threw myself into it with the fervor of a monk copying manuscripts. My English, while consistently earning me the coveted grade of 5 (equivalent to 100), was purely academic—a museum piece polished to perfection but never tested in the wild.

Our school was relatively privileged, equipped with a language laboratory where we practiced pronunciation with the dedication of opera singers preparing for La Scala. We learned British English, naturally—the Queen's English, as proper and starched as a Victorian collar. Our beloved video course, "Follow Me!" starring the impeccably British Francis Matthews, had become our window into the English-speaking world.

For the uninitiated, "Follow Me!" was a television series produced by the BBC in the late 1970s, designed to teach English to non-native speakers. Francis Matthews, with his perfect diction and patient demeanor, had become something of a household name in Soviet apartments. We knew his facial expressions better than those of our own relatives.

To watch these educational treasures, our school possessed an Elektronika VM-12—the first Soviet VHS-compatible videocassette recorder. This magnificent beast of Soviet engineering was allegedly based on the Japanese Panasonic NV-2000, though at the time, I cared less about its pedigree than about its ability to replay Matthews explaining the difference between "shall" and "will" for the hundredth time.

I dedicated several hours daily to English conversation practice, writing elaborate monologues about myself, my parents, our apartment, and my hopes for the future. I memorized these scripts with the intensity of an actor preparing for Hamlet, complete with dramatic pauses and perfectly enunciated consonants. In my mind, all English was British English—crisp, proper, and spoken with the authority of centuries of empire.

The Tale of Two Supply Chains

But before we get to the cultural collision, we must discuss the coupons—those magical pieces of paper that opened doors to a parallel Soviet reality.

You see, the Soviet Union operated on what I can only describe as a dual-economy system. Picture two rivers flowing through the same landscape: one crystal clear and abundant, the other muddy and intermittent. The first river served the nomenclature—the party elite, government officials, and their families. The second served everyone else.

While the nomenclature enjoyed Italian salami and Scottish whiskey, regular workers, particularly those living in the periphery (a mere 100 miles from Moscow was considered periphery), often lacked regular access to meat and, rather embarrassingly, toilet paper.

Ah, toilet paper—the great equalizer of human dignity.

The vast majority of Soviet citizens used newspapers for sanitary purposes, leading to a rich tradition of bathroom humor. Certain propaganda publications were particularly prized for their absorbent qualities, and jokes about which political slogans made the best toilet paper circulated more widely than the newspapers themselves.

Armed with our special coupons, we acquired toilet paper (a luxury that made my mother nearly weep with joy), Italian salami (which my father eyed with the suspicion of a customs officer), and Pepsi-Cola.

Yes, Pepsi-Cola was available in the Soviet Union, thanks to one of the most unusual trade relationships in Cold War history. In 1959, PepsiCo's CEO Donald Kendall offered Premier Khrushchev a Pepsi at an American exhibition in Moscow. The Soviet leader's positive reaction led to a barter system that would leave modern economists scratching their heads in bewilderment. Since Soviet rubles had no international value, Pepsi exchanged Stolichnaya vodka for Pepsi products, which they then sold in the United States.

But I digress. The point is, we had Pepsi.

We also received an ice maker—a plastic tray designed to create twelve perfect ice cubes in a home freezer. The instructions were crystal clear:

"Put ice in a special transparent vessel on the table. Americans love ice!"

This seemed bizarre to us. In Soviet culture, cold drinks were viewed with suspicion, particularly for children and women. We believed that consuming cold beverages could lead to everything from sore throats to infertility. The idea that anyone would voluntarily add ice to their drinks struck us as either remarkably brave or remarkably foolish.

Setting the Stage

Our apartment was, by Soviet standards, palatial. Located on the third floor of a novel white brick building, it boasted three bedrooms—an almost unimaginable luxury for most Soviet families. This privilege came courtesy of my parents' engineering positions in the construction industry, which placed them slightly higher on the housing allocation food chain.

The centerpiece of our dining room was a magnificent wall-to-wall Persian carpet. This piece of art wasn't just a floor covering; it was a symbol of status. The background was pristine white, decorated with intricate Oriental patterns that seemed to shift in the light like a magnificent kaleidoscope.

My mother treated this carpet with special reverence typically reserved for religious artifacts.

We had separate slippers—soft-soled, silent slippers—that we wore exclusively in the dining room.

She vacuumed it daily, moving furniture with the precision of a chess master to ensure every fiber received attention. The carpet represented everything beautiful and precious in our controlled world, a small patch of paradise in our concrete reality.

Our living room housed an enormous bookcase that stretched from floor to ceiling, packed with several hundred volumes. Among them were American authors: Theodore Dreiser, Ernest Hemingway, O. Henry, and others whose works had been translated into Russian and deemed acceptable by Soviet censors. These books were my windows into American life, though I wouldn't realize until much later how filtered and incomplete that view was.

The Day of Reckoning

The day finally arrived—a typical rainy summer day that seemed designed by nature to add dramatic tension to our international encounter. Three white boys from Baltimore, Maryland, accompanied by their English literature teacher, appeared at our door like visitors from another planet.

The first cultural shock occurred before anyone had spoken a word.

My mother tried to indicate where our guests should place their shoes and pointed toward the special slippers reserved for the dining room.

Soviet streets were notoriously unpredictable terrain, often muddy and sometimes unpaved, requiring special footwear or galoshes (which were among the most popular items in Soviet shoe stores) to navigate safely.

The Americans looked at her pointing gesture, looked at the slippers, looked at each other, and then—with the casual confidence of people accustomed to walking wherever they pleased—strode directly into our dining room wearing their New Balance sneakers.

My mother nearly fainted!

I watched in slow-motion horror as those foreign sneakers made contact with our pristine Persian carpet, leaving marks that would likely outlive the Soviet Union itself. The Americans seemed completely unaware of the cultural catastrophe they had just committed. To them, it was simply walking into a room. To my mother, it was roughly equivalent to tap-dancing on the Mona Lisa.

But she was Soviet-trained in hospitality, which meant that even during a cardiac event, she would continue to serve guests. She laid out salads with military precision, arranged slices of precious salami like flower petals, filled glasses with Pepsi-Cola, and placed ice cubes in the crystal vase from Prague—a possession she treasured as both a status symbol and a piece of art.

The Americans ate nothing. .. Looking back, I suspect they had received their own manila folder of instructions, probably warning them about suspicious foreign food and beverages. While we had been taught to honor guests by offering our finest provisions, they had apparently been taught to politely decline everything. The ice and cola disappeared quickly—perhaps ice really was the universal American language—but the carefully prepared food remained untouched.

Lost in Translation

When the conversation began, I launched into my carefully memorized introduction, delivered in what I believed was perfect English. The Americans listened politely, but I gradually realized that something was terribly wrong.

They spoke English, certainly, but it wasn't the English I knew. Where was the crisp BBC pronunciation? Where were the perfectly enunciated consonants and the careful observance of every grammatical rule? These teenagers spoke with contractions, slang, and a rhythm that bore no resemblance to Francis Matthews' measured cadences.

I pretended to understand everything while frantically trying to decode their rapid-fire American English.

It was like being fluent in classical Latin and suddenly finding yourself in a Roman marketplace—technically the same language, but practically incomprehensible.

Their teacher, mercifully, led the conversation toward literature, and suddenly we found common ground. The boys had been well-prepared and demonstrated impressive knowledge of Russian classical literature. They knew Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Dostoyevsky—not just their names, but actual details about their works and significance.

Eager to reciprocate, I proudly produced several volumes of Theodore Dreiser from our bookshelf—a special edition with golden spines that my parents had acquired through literary connections. I expected recognition, perhaps even admiration for our Soviet appreciation of American literature.

The boys looked at the books politely but blankly.

It became clear that they had never read Dreiser, despite his status as a towering figure in American literature according to our Soviet textbooks. This was my first glimpse into the reality that what we considered essential American culture might not actually be central to contemporary American life.

Our discussion of Hemingway proved more fruitful—we had mutual ground there, though I suspect we emphasized different aspects of his work. The Soviet literary establishment celebrated Hemingway's anti-war themes and his criticism of American capitalism, while the Americans probably appreciated his adventurous spirit and spare prose style.

O. Henry was known only to their teacher, who spoke with genuine excitement about "The Gift of the Magi." I had read this story multiple times, always wondering why Americans would celebrate a tale about poverty and sacrifice that seemed to critique the very materialism we associated with American culture.

The Exchange of Dreams

The formal conclusion of our meeting involved the traditional exchange of gifts—a ritual that revealed as much about our respective cultures as hours of conversation could have.

We presented them with traditional Russian Matryoshka dolls and other souvenirs that screamed "authentic Soviet experience" in the way that gift shop items do worldwide. These were the kind of presents that would sit on American bedroom shelves for years, occasionally eliciting the story:

"Oh, that? I got it when I visited Russia in high school."

In return, they gave me a T-shirt from the Washington Wizards basketball team. Someone had clearly done their homework—I was passionate about basketball at the time, and this gift demonstrated thoughtful preparation. That T-shirt became one of my most treasured possessions, a tangible piece of America that I could wear.

But the real treasure came from their teacher: a hardcover picture atlas titled "Our Fifty States" published by the National Geographic Society. This wasn't just a book; it was a window into an entire continent of possibilities.

The atlas was gorgeous—packed with color photographs, detailed maps, and illustrations that brought each state to life on the page. The text was clear and informative, organized by region, with each state summarized over four pages that included brief timelines, details on natural resources and physical features, climate data, and intriguing "did you know" facts that turned American geography into a collection of adventure stories.

I was so moved by this gesture that I impulsively gave the teacher my military watch—a timepiece I had bought at a special military shop for 25 rubles and had been saving for myself. The teacher graciously accepted it and later gave it to one of her students, completing a circle of international goodwill that seemed to justify the entire Cold War cultural exchange program.

The Dream Takes Root

After our guests departed, leaving only memories and sneaker marks on our Persian carpet, I settled into a deep relationship with that National Geographic atlas. It became my evening companion, my weekend adventure, my escape hatch from Soviet reality.

I read it regularly, studying the photographs with the dedication of a medieval monk illuminating manuscripts. Each state revealed landscapes and possibilities that seemed as fantastical as fairy tale kingdoms. Desert vistas, mountain ranges, endless prairies, coastal cliffs—

America appeared to be a continent-sized theme park of geographical wonders.

Among all these marvels, one location captured my imagination completely: Niagara Falls.

In the atlas, Niagara Falls stood out as one of the most remarkable places on Earth—a thundering cascade of water that showcased the raw power of nature harnessed by human engineering. The photographs revealed rainbows dancing in the mist, tourists in yellow raincoats standing impossibly close to the torrential waters, and viewing platforms that appeared to float above the churning foam below.

I dreamed about Niagara Falls with the intensity that other teenagers reserved for rock stars or sports heroes. It became my personal symbol of the America I couldn't visit—beautiful, powerful, and tantalizingly out of reach.

The atlas lived on my desk for years, accumulating pencil marks, coffee stains, and the wear patterns of constant use. I memorized state capitals, studied population statistics, and traced highway routes with my finger as if planning road trips I knew I'd never take.

When I eventually left Russia, I couldn't bring myself to pack the atlas. It belonged to a time and place where dreams seemed impossible, and I was moving toward a future where I hoped they might become real.

So, I left it behind, never imagining that someday I would regret that decision.

The Long Arc of Dreams

Life, as it often does, followed an unpredictable trajectory. The Soviet Union eventually collapsed, borders opened, and the world rearranged itself in ways that would have seemed impossible during my teenage years. Through a combination of hard work, luck, and the kind of historical timing that makes biographies seem scripted, I eventually found myself in America—not as a tourist or visitor, but as a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University.

Thirty-five years after three American teenagers had crossed our Persian carpet in their New Balance sneakers, I was living in New Haven, Connecticut, pursuing research that would have been unimaginable during my Soviet youth.

The first weekend after my arrival, I gathered my family—my wife and three daughters—and announced our inaugural American adventure.

"We're going to Niagara Falls,"

I declared.

My wife looked at me as if I had announced plans to visit Mars.

"This weekend? You just started work. Shouldn't we be settling in, exploring New Haven, maybe finding a good grocery store?"

"No," I said, with the kind of certainty that comes from carrying a dream for three and a half decades.

"First, we see Niagara Falls."

I approached my new supervisor, a distinguished professor who had graciously welcomed me into his research group, and requested an extra day off.

"You need Monday off?" he asked, puzzled. "You just started. What's so urgent?"

"Professor," I said, trying to explain without sounding completely mad, "I have a dream I need to fulfill."

"What dream?"

"To visit Niagara Falls."

He grimaced in the way that Americans do when confronted with behavior that doesn't compute with their cultural programming.

"I'm American, and I've never been to Niagara Falls. I have no intention of going."

"I'm not American," I replied, "but I have a dream. So, could I?"

The professor granted my request, though I suspect he filed it under "strange foreign customs" in his mental catalog of international academic exchange experiences.

The Dream Fulfilled

That weekend, we loaded our rental car and drove north through the changing landscape of upstate New York. My daughters, aged 13, 10, and 4, treated this expedition with the enthusiasm typically reserved for dental appointments. To them, it was just another parental obsession to be endured.

They had no context to understand that their father was completing a circle that had been drawn thirty-five years earlier in a Soviet apartment by three American teenagers and a National Geographic atlas.

As we approached Niagara Falls, I felt the kind of anticipation usually associated with religious pilgrimages or first dates. Would reality match the decades-old images burned into my memory? Would the falls live up to the mythical status they had acquired during my Soviet youth?

The first sight of the falls answered every question.

They were magnificent—more powerful, more beautiful, more overwhelming than any photograph could capture. The thunder of cascading water filled the air like a constant symphony. Rainbow mists danced in the sunlight. Tourists from around the world stood in yellow raincoats, their faces reflecting the same awe I felt.

I stood there with my family, watching millions of gallons of water plunge into the churning pool below, and felt the completion of something that had begun when I was sixteen years old in a world that no longer existed.

My daughters eventually warmed to the spectacle, taking selfies and videos that they would share with friends back home. My wife appreciated the natural beauty, though she remained puzzled by the intensity of my emotional reaction to what was, after all, just a very large waterfall.

But for me, Niagara Falls represented something more profound: proof that dreams deferred are not necessarily dreams denied. That teenage boy studying an atlas in Soviet Russia had planted a seed that took thirty-five years to bloom, but bloom it did.

The Larger Lesson

Reflecting on that summer day in 1986, I can see it as a perfect microcosm of the cultural collision between East and West that was reshaping our world. Teenagers, separated by an ocean and an ideology, were trying to connect across a divide that seemed insurmountable.

We prepared for each other like anthropologists studying remote tribes. They learned about Russian literature; we memorized American slang. We purchased special food; they probably received instructions to avoid foreign cuisine. We put on our finest clothes and cleaned our most precious possessions; they showed up in sneakers and jeans, treating our formal occasion as a casual visit.

The comedy of errors that followed—the carpet catastrophe, the language confusion, the literary misunderstandings—revealed how little we actually knew about each other despite careful preparation.

We were like actors in different plays, sharing the same stage but working from completely different scripts.

Yet somehow, through confusion, genuine connections were made and dreams were planted. In fact, we are more alike than different. We dream of places we've never seen, hope for futures barely imaginable, and surprise ourselves with our achievements. So, that atlas showed me that the world was vaster and more wondrous than I had imagined. It suggested that the borders that seemed so permanent might be more fluid than they appeared. It even whispered that someday, somehow, the impossible might become possible. In 1986, the notion that a Soviet teenager could live and work in America seemed as fantastical as space travel. The Iron Curtain felt permanent, and the ideological divide appeared unbridgeable. But history, as we've learned, has a sense of humor. Walls fall, curtains rise, and teenagers grow up to live lives once seen as impossible…

P.S. That T-shirt served me for years, and after it wore out, it hung on my wall like a flag of friendship. The atlas remained on my desk throughout Medical School as a reminder of the world's wonders. The carpet, by the way, never quite recovered. My mother kept it for several years, and when she looked at those faded sneaker marks, she remembered the day America entered our dining room, leaving footprints on our hearts.

When I eventually made it to America, I realized I'd left the atlas behind in Russia, thinking it belonged to dreams I could never reach. But I was wrong.

Dreams belong to dreamers who adapt and evolve…

About the Creator

Baruh Polis

Neuroscientist, poet, and educator—bridging science and art to advance brain health and craft words that stir the soul and spark curiosity.

Comments (1)

Sounds like an interesting start. Reminds me of how things were changing back then. I remember similar excitement when opportunities like this came up.