Why is it so dangerous to step on a rusty nail?

Tetanus

In the 5th century,

Greek physician Hippocrates, creator of the Hippocratic Oath,

was sailing with a very ill shipmaster. The captain was suffering

a nasty infection that caused his jaws to press together,

his teeth to lock up, and the muscles in his neck and spine

to spasm. Hippocrates dutifully recorded

these symptoms, but he was unable to treat

the mysterious disease. And six days later,

the shipmaster succumbed to his illness. Today, we know this account to be one

of the first recorded cases of tetanus, and thankfully, modern physicians

are much more prepared to handle this peculiar infection. Unlike other common bacterial infections

like tuberculosis and strep throat, tetanus doesn’t pass

from person to person. Instead, the offending bacterium,

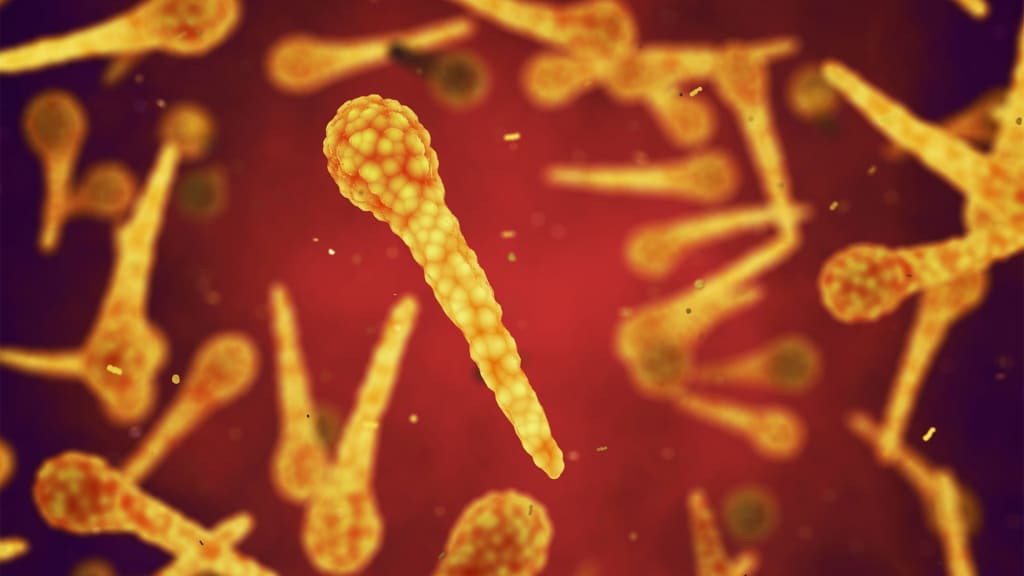

known as Clostridium tetani, infects the body

through cuts and abrasions. These infection sites are why tetanus

is so strongly associated with rusty nails and scrap metal,

which can cause such wounds, but the condition's connection to rust

is actually much less direct. Clostridium tetani bacteria are often

found in soil, manure, and dead leaves, where they can survive for years

in the form of spores, even amidst extreme heat and dryness. These piles of organic material can

sit undisturbed for long periods, potentially concealing old metal,

which rusts over time. So, if someone does blunder into this

environment and cuts themselves, it would likely increase

their odds of infection. Especially since rusty metal can create

jagged wounds with lots of deoxygenated dead tissue

for them to latch on to. Once in the body, the spores

begin to germinate. This process releases several toxins,

including deadly tetanus toxin. Nerve endings soak up this toxin, drawing it into the brain and spinal cord

where it wreaks havoc on interneurons. Typically, these work alongside motor

neurons to regulate our muscle actions, from endeavors as complex as kicking

a ball to those as simple as breathing. But by blocking neurotransmitters

released by interneurons, tetanus toxin causes uncontrollable

muscle contractions and spasms. Typically within 7 to 10 days

of infection, patients begin experiencing general aches,

trouble swallowing, and lockjaw. The head and neck tend

to show symptoms first. But as the toxin spreads,

stronger muscle groups become more rigid, leading to a frightening arching

of the back. Left untreated, these spasms

become more extreme, eventually seizing the muscles

in the windpipe and chest, leading patients to suffocate

within 72 hours of symptoms appearing. Without treatment, tetanus has

an extremely low rate of survival. But fortunately, medical professionals

have developed a robust plan to handle a tetanus diagnosis. First, doctors clean the infected wound

and administer antibiotics, killing the bacteria and preventing

further toxin production. Then, they inject antitoxin to neutralize

any tetanus toxin still in the body that has yet to enter

the central nervous system. Finally, patients begin a several week

period of supportive care, which can include muscle relaxants

to stop spasms and ventilators to prevent suffocation. In the days of Hippocrates, the only

course of treatment was to wait and hope. But now we know the best time to tackle

Clostridium tetani is before an infection even takes place. Tetanus vaccines— originally developed

in the early 1920s— are crucial to preventing tetanus

and stopping its spread. Experts recommend a series of shots and

boosters beginning at two months old and ending around age 12. Yet over 20,000 infants still die

of tetanus every year, mostly in low and middle income countries

where vaccine access is limited, including South Asia

and sub-Saharan Africa. And newborn babies are especially at risk

if their mothers are unvaccinated, as Clostridium tetani can infect

a newborn's umbilical stump. Though vaccinating mothers during

pregnancy can help with this problem. The fact is tetanus remains a significant

threat to human health. So people should get vaccinated and take measures to prevent infection

after cutting themselves— whether it’s on a rusty nail

or a 2,400-year-old ship anchor.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.