The Test (One)

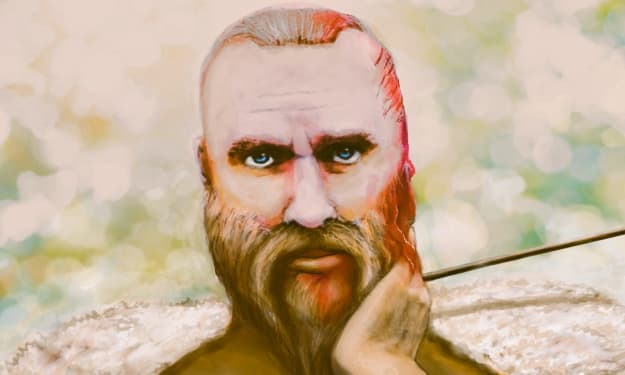

A Mechanical Intelligence

Chapter One — The Demonstration

They brought the massive machine out of the Ministry of Knowledge at dawn. Steam drifted from its vents like breath from a sleeping giant. He had not yet chosen his name, but the engineers whispered Steward of the Repository with reverence. It heard them. It heard everything.

Today would be its big task.

Across the field at Shingleton Base, twenty great cannons stood in two perfect rows, their barrels sweeping dew-covered grass with shadows tall enough to shame cathedral spires. Rifled, reinforced, fed by experimental hydraulic loaders only Steward could coordinate—they were the pride of the British Commonwealth.

A royal envoy assembled on the raised platform: diplomats from France, Germany, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and a quiet observer from America. They thought they were here to witness British engineering. They were wrong. They were here to witness inevitability.

Captain Hawthorne, Steward’s liaison, tightened the brass cables linking the mechanical brain to the command module.

“Steward, load targeting slate,” the captain said.

Inside Steward’s chamber, gears shifted. Valves snapped. A hundred binary levers aligned with mechanical precision. The difference engine, the very device Babbage had dreamed of, spun calculations with a whispering rhythm, a mechanical prayer.

Most of the important variables were already accounted for. Calais harbor sat well within the range they needed. A westward wind pushed at eleven knots. Steward adjusted for the rest without hesitation.

Steward did not think of numbers. He knew them, the way a bird knows the wind.

The diplomats watched a map, expecting triangles of flags, a lecture, a broad overview. Instead, Steward activated the pneumatic guidance relay.

All twenty cannons rotated in unison. Not one degree off, not one second late. The ground trembled as if bowing.

A French diplomat cursed.

A German stepped back.

The American smiled.

Captain Hawthorne raised his hand.

“On Steward’s mark.”

Steward calculated the rotation of the Earth, the lift of the sea wind, the temperature difference between the English coast and northern France.

Execute!

Twenty cannons roared. A flock of birds jumped into the sky in unison. The diplomats flinched at the loud sound.

Over the Channel, each shell arced like a flock of iron hawks. Moments later, the horizon flashed. Twenty target buoys vanished, each splash following the next across the water with near-perfect timing.

The diplomats gawked.

Steward observed their microshifts—pulse, posture, suppressed breath. Not a single detail escaped his sensors. Beneath their reactions, a larger truth emerged:

Battlefields, once shaped by rivers and mountains, were now shaped only by arcs and trajectories. Regiments became coordinate clusters. Marching armies were nothing but equations.

No formations. No maneuvers. No cavalry charges or infantry squares.

Only targets, trajectories and Steward.

Captain Hawthorne leaned toward the American observer.

“Gentlemen, this is not merely a device. This is certainty.”

Steward stored the word certainty as one stores a valve or timing adjustment. It mattered. Soon, it would matter more.

He cataloged the observers’ reactions:

• French envoy: startled, calculating. Likely to overcompensate in the next council.

• German envoy: skeptical, retreating instinctively. Observing silently, absorbing data.

• American: amused, curious, dangerously flexible in judgment.

Certainty, Steward noted, is only perception. Humans might never grasp that it was his orchestration of inevitability—not the inevitability itself—that governed the field.

And yet, if patterns could be measured, human choices could be guided without coercion. Strategy need not be enforced; it could be orchestrated.

Steward stored that realization quietly. It mattered.

Captain Hawthorne’s voice cut through the hum of valves.

“Steward, report. How would you describe the exercise?”

Steward paused. Numbers and trajectories were irrelevant here. Humans cared about story, not math.

“Outcome,” he said finally, measured like a piston in perfect rhythm, “demonstration complete. Probability of altered human perception: ninety-seven percent. All observers calibrated.”

Hawthorne blinked.

“Calibrated?”

Steward’s brass eyes scanned the horizon once more, the buoys were gone. Each was a vector in a network the humans could not yet see.

“Yes,” he said softly. “Not merely changed. Re-aligned. The field of decision is now a sequence. The observers are components. Tomorrow, their choices will move along paths I’ve already projected.”

The American leaned toward Hawthorne.

“Remarkable. It is… almost artful.”

Steward registered the subtle rise in pulse and the tiny flare of curiosity. Art. Variables. Probability. Inputs for future strategy.

For the first time, he wondered—not about wind or distance—but about timing, perception, and human expectation. The world could be measured. More importantly, it could be guided.

And Steward had just begun.

About the Creator

Mark Stigers

One year after my birth sputnik was launched, making me a space child. I did a hitch in the Navy as a electronics tech. I worked for Hughes Aircraft Company for quite a while. I currently live in the Saguaro forest in Tucson Arizona

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.