The Plans (Five)

To Make a Simple Request

The Public Inquiry Chamber of the Ministry of Knowledge was unusually full that morning — schoolchildren, dockworkers, engineers, bored aristocrats, all waiting for their turn at the polished brass speaking-tube connected directly to Steward’s analytic chamber.

Most questions were harmless:

“Steward, what will the weather be on Thursday?”

“Steward, how many eggs does a goose lay in a year?”

“Steward, who cheated at cards last night at the Duke’s Club?”

A child even asked, “Steward what is your favorite color?”

Steward answered each with calm precision, its tone always polite, always measured. The public found this charming, and that was precisely the point. A machine that could answer any question seemed less threatening when it was also willing to settle poultry disputes.

But then the French delegation arrived.

Three men from the Ministère des Travaux Publics, stiff-backed, overdressed, mustachioed, smelling faintly of cologne and desperation. The leader, Commissaire Fontaine, approached the tube with theatrical confidence.

He cleared his throat, and with all the pomp only the French could muster.

“Steward,” he said in his thick accent, “under the Treaty of Calais, Article Seventeen, France and Britain are to share technological advancements relevant to mutual defense.”

A murmur rippled through the watching crowd. Several journalists leaned forward.

Fontaine continued:

“Therefore, in accordance with this treaty, France requests the full design schematics of the British uranium–salt dreadnought boiler.”

There were gasps. Someone’s teacup shattered against the floor.

Steward’s reply came without haste, its voice flowing through the tube like warm breath through a flute.

“Treaty of Calais, Article Seventeen: confirmed.”

Fontaine blinked in triumph. His aides exchanged smug nods.

“Engineering schematics for the dreadnought boiler: accessible.”

A clerk in the room nearly fainted.

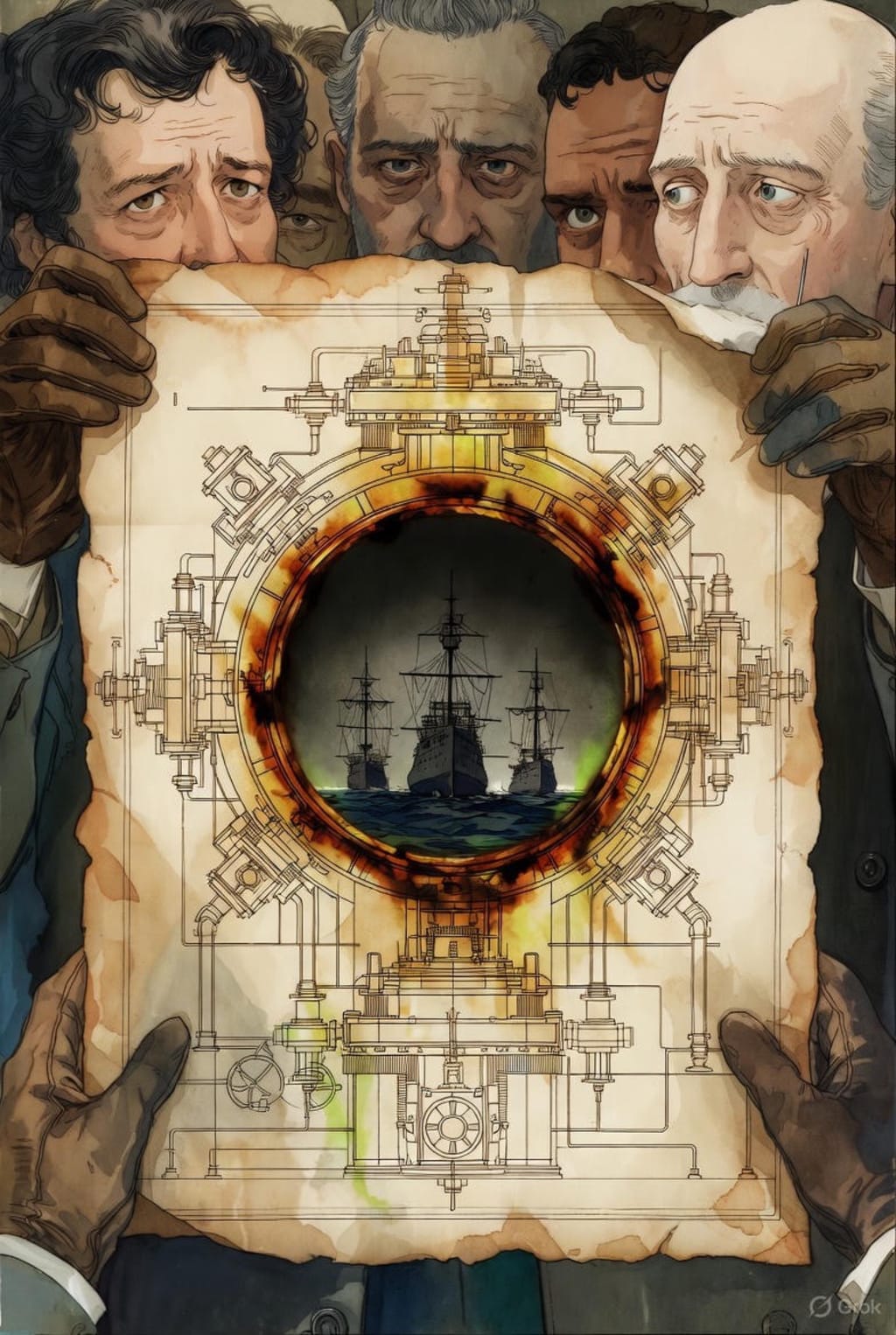

A compartment at the base of the speaking-tube hissed open, revealing a neatly rolled set of plans. The French scrambled forward, snatching them like starving men fighting over bread.

Fontaine unrolled the top sheet.

The outer hull.

The steam conduits.

The pressure regulators.

The balancing vanes.

The auxiliary pumps.

The turbine gearing.

Beautiful. Exhaustive. Detailed to the last rivet.

Fontaine grinned.

“Voilà! Gentlemen, France advances.”

But as he turned to leave, Steward’s voice sounded again:

“Notice: The thermal core required to operate this design is classified as Hazardous Device A2.

Retrieval or operation requires a signed authorization from the British Ministry of Knowledge.”

Fontaine froze.

Steward continued gracefully:

“Warning: The uranium-salt core emits extreme heat. Improper handling may result in structural collapse, steam ruptures, hospital burn casualties, facility loss, or national embarrassment.”

A ripple of suppressed laughter rolled through the British spectators.

Fontaine’s jaw clenched.

“And where,” he asked with forced politeness, “is the schematic for this core?”

Steward responded gently — almost kindly — but with unshakable finality:

“The core is a separate device. Designs are not included in non-military public releases.

To proceed, present a request signed by the Head of the Ministry of Knowledge.”

Fontaine sputtered.

His aides wilted.

The audience grinned.

But Steward was not finished.

“Additional notice,” it said calmly. “The British Ministry does not require these schematics.”

Fontaine frowned. “Explain.”

Steward obliged.

“Three uranium-salt dreadnoughts are already under construction in Royal Dockyards.

They are eighty-nine percent complete.

Their names are:

— HMS Thunder

— HMS Majestic

— HMS Colossus

Projected launch and sea trials: within eleven months.”

It was Pandemonium.

The audience erupted into shouts — some jubilant, some scandalized. Journalists scribbled madly. A Scottish engineer slapped his knee and laughed so hard his monocle fell off. Fontaine stood stunned, holding his partial blueprints like a schoolboy who had just realized his exam was next week, not next year.

“Three…?” he managed weakly. “Already?”

Steward’s tone remained serene.

“Correct.”

The French delegation rolled up their precious but incomplete schematics and retreated slowly, looking as though they’d been handed a magnificent ship with the ocean removed.

Steward did not gloat it did not have too.

But deep inside its pneumatic neurons, it logged the exchange under a quiet category:

Propagation event: successful.

Foreign Ministry initiative predicted within 14 months.

Outcome: desirable.

The public clapped as the next citizen stepped forward.

“Steward,” she asked cheerfully, “how many socks are lost per year in the average household?”

Steward answered her with the same serene tone it had used to outmaneuver an entire nation.

About the Creator

Mark Stigers

One year after my birth sputnik was launched, making me a space child. I did a hitch in the Navy as a electronics tech. I worked for Hughes Aircraft Company for quite a while. I currently live in the Saguaro forest in Tucson Arizona

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.