Work is the second chapter in the book Lost Voices of the Edwardians by Max Arthur.

Can “Work” really change so much from the late 1800s up until today, 2025? The truth is “Yes!”

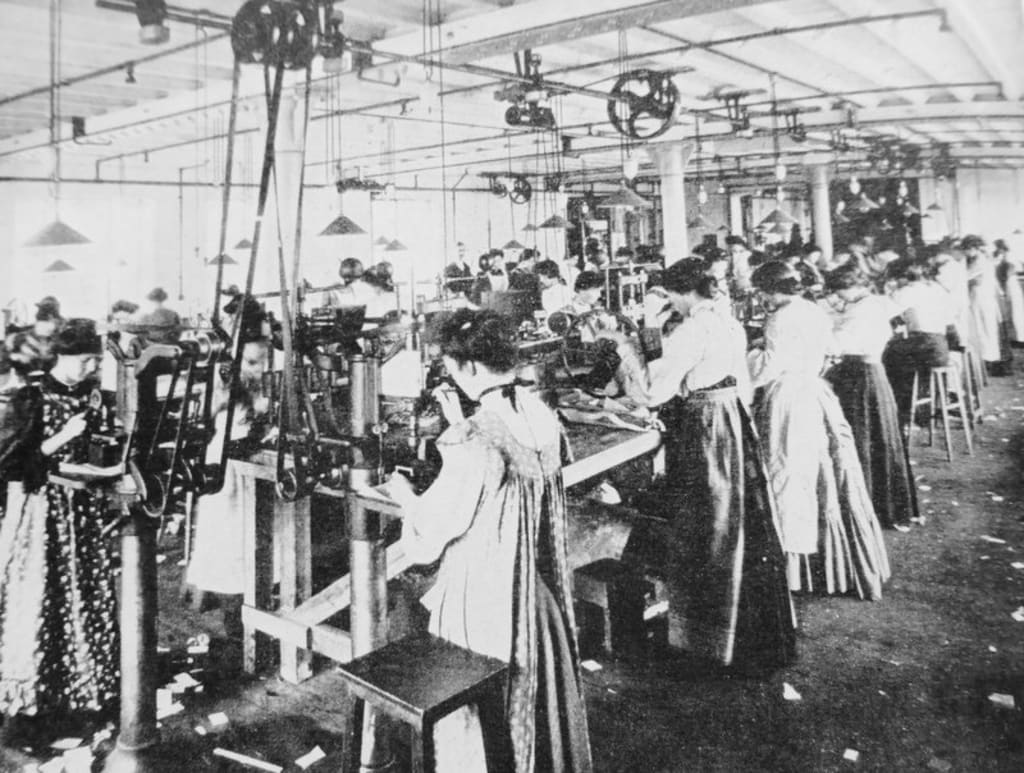

Jobs have changed tremendously over the last century. Some Edwardian jobs are no longer needed and therefore no longer exist, whilst today, some jobs just did not exist back then because, quite simply, we live in a completely different world.

In the Edwardian Era, there were no Laws to protect the people, so the Health and Safety ‘record’ did not exist, and employers could do and pay basically whatever they wanted to. It was a very hard time to have to work, with many finding ‘any job’ to get a little money. Work was very long hours with very little pay which very often kept many in a continual state of illness, but they still had to work, (there was no sick pay). Rent needed to be paid, as well as buying food and clothes because the Workhouse was to be avoided at all costs!

Here are some very real-life experiences by Edwardian workers — in their own words:

Ray Head: “I went to work for the Post office in the City of London. Hounslow was an agricultural town in those days, a little rural place. Most people living there worked on the land. Most people working in London still came from the area close to the City — I was an exception. Most of these people walked to work. There were thousands of houses in Lambeth, Southwark, Whitechapel and Dalston, and all the inhabitants used to walk to work in offices which were really clerical factories. Everything was so labour-intensive. Typewriters were only just beginning and the telephone was a luxury for the very, very few, so everything was written by hand. In the banks, all the ledgers were done by hand and there was a great deal of clerical work to do. I used to wear a still collar, tie, trousers, heavy boots, a bowler hat and an umbrella. You needed heavy boots because they soon wore out with all the walking. The people higher up wore top hats. The atmosphere in the office was pretty formal. Contact between men and women was very limited. We were kept apart and we dined in separate dining rooms. There was no palliness with the bosses. We were very humble. In spite of all this, we were happy. It almost felt like a club.”

Bill Taylor: “I couldn’t read or write, so when a form gave me a delivery note, they would give me the orders at night for the following morning. I’d take the note home and try to work out the route which I was going to do, using a map. I’d look on the map for the names of places that were the same as those on my delivery note. I’d make a line right the way across the map, say from Holloway up to Barnet and on to the North Road to Darlington. Each big town I was going through, I’d mark on the map. So when I pulled up at that town, I’d get the map out and ask people which was the best way to the next town I’d marked. That was how I got on. I had to go from one town to another asking the way because I couldn’t read any of the signs on the road. None of the guv’nors I worked for ever knew I couldn’t read. If they did know someone couldn’t read, they would fire them, saying, ‘you’re no good to me.’ It had been easier when I’d been on the horses, because some of the horses knew where they were going. They helped a lot. But when it changed to motors, I had to do it all myself. I had a lot of tricks to get me through, though.”

Jane Banks: “I became a pupil teacher. You sat for what was called Preliminary Certificate of Education, and if you passed that you went as a pupil teacher in a school. I went back to the primary school I had been to, and I became a pupil teacher there. I was seventeen. I worked four days a week in the school and every Tuesday went back to the county school to keep up my book work, otherwise I would have let that go and would have lost half of it before I sat for my final teaching exam. You weren’t in charge of a class. You had to follow the teachers around to learn the procedure, and you had to work very hard as a pupil teacher. You were fully occupied the whole time. There was no slacking. You had to look after the stock room and cut up the necessary needlework for children, and you had to take classes occasionally. I got ten shillings a month, which I had to go to the municipal buildings to collect. All the other teachers had their cheques sent to them, but I was so young. I had to go and fetch it. Ten shillings a month! You see, little girls who went into service, they used to get ten shillings a month, but they also got a roof over their head, and they got their food given them. But when you were a pupil teacher, your ten shillings had to do everything. In the second year you got thirteen shillings and fourpence a month.”

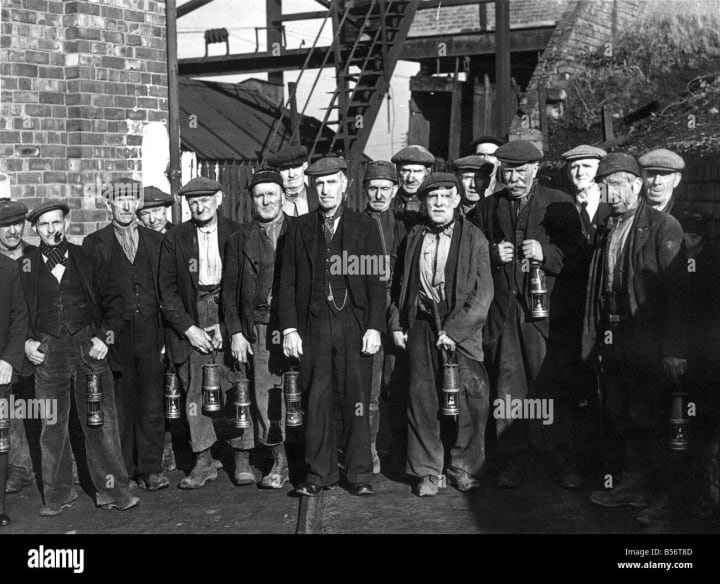

George Cole: “I left school when I turned fourteen. I left at teatime, had a drink of tea with my dad, walked up to Seaham Colliery, signed on and started work the next morning. I was down the pit at ten minutes to five on the day after I finished school.”

John William Dorgan: “My father worked in the mine, but instead of working on the coal side,

was a ‘stoneman’. When the coal was taken from the seam, the mine had to be developed further. So the stone men took the roof down to make a roadway about ten to twelve feet high. He started work at four in the afternoon and finished at two in the morning. There were no electric cutters. He had to drill holes into the stone. That brought out the stone dust, and it gave him chest trouble and he lost a lot of work that way.”

We need to remember that at this time, there were no uniforms or masks or helmets to wear and no Health and Safety rules, and everything was done manually because there was no electricity. It is no wonder that these workers became so ill!

Jack Hepplestone: “Everyone joined the union as soon as they started. A man came around and you’d pay him fourpence every week and that kept your book in order. When it came to any raises, you’d have a committee meeting at a pub. I went now and again. The union was very important to us, seeing the rules and regulations were kept, but we never had a strike in my four years in the pit. Every so often, there was a parade and a miners’ meeting. People were proud of being miners. There was a Miners’ Institute and people went down there on a Saturday night and a Sunday for a pint and a singsong.”

The Miner’s National Association was founded in November 1863 and it took a long time to ‘get off the ground’. Back then, the workers found that it was the only ‘protection’ they had with regards to working conditions. Today, we simply take ‘unions’ for granted and do not know life without them.

Albert ‘Smiler’ Marshall: “If you were an apprentice, or you had a job to go to, you could leave school at thirteen, but if not, you had to stay until you were fourteen. After that, you had to leave whether you had a job or not. I was apprenticed to the nearest shipyard, so I left school at thirteen. I changed from knickerbockers into trousers. At the shipyard, I was working with a Yorkshireman who was making all these beautiful doors. All I was doing was handing him the screwdrivers and saws and different tools while he was doing his work. In other words, I was a first-class-carpenter’s labourer. At the end of my first week’s work, I got two shillings and fourpence and felt quite rich.”

William George Holbrook: “I started work at a farm across the road from us. It was still dark in February and I used to start at six in the morning. At nine o’clock, I had a bit of bread and cheese and then worked until six in the evening. We worked six days a week — all day Saturday — and we got six shillings. I used to give my mother five and sixpence, so I had sixpence to spend. So, once a week, I went to the swimming baths at East Ham. That cost me thruppence for train fare and thruppence for the baths.”

Freda Ruben: “My mother went out washing. She charged one and six for the whole wash. She used to go and do it in their homes. I remember one day when she’d done a day’s washing she came home — and our Morrie was born! She was so heavily pregnant and we’d begged her not to go, but she needed the money, and she had my brother as soon as she’d got back home. She didn’t go to hospital — she just had Morrie there and then after a hard day’s washing.”

Joseph Henry Yarwood: “I had a job while I was still at school. I worked for a baker. I used to help him pull the barrow round delivering bread. We started at nine in the morning and we worked until six in the evening, and at the end of the day he gave me ninepence and a loaf.” “I got a job with a greengrocer who supplied high-class houses in the Clapham Common area. I started at nine o’clock and delivered baskets of fruit and vegetables to the big houses and he gave me ninepence and a bag of vegetables.”

Mrs Brown: “When I was twenty I left to be a nurse. I started at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle, which was a new hospital in 1907. I was there until my feet let me down, I had terribly blistered feet. I worked sixty-five hours a week and got no wages for three months. I had nothing except my keep, as I lived in. At night I used to be so tired I used to scream when I put my feet on the bed. It was exceptionally strict. You were never allowed to start a conversation, you were never allowed to speak unless you were spoken to, and you were never allowed to walk in front of a senior. You had to do exactly as you were told — you could never answer back. You had no social life at all. I remember saying to a sister that I had an appointment with my young man, and she said, ‘Nurses in training have no business to make appointments.’ I wasn’t allowed to go.”

As we have seen, these ‘jobs’ are so different when compared to today (2025), and the age differences just stand out. Being apprenticed at thirteen! It just doesn’t happen today. The very low wages also stand out, although we must remember the difference in ‘coin’ from then until now, but these workers sometimes felt quite ‘rich’ with their weekly wages.

Today, we cannot imagine working like this because we are lucky enough to live in a time of support for the ordinary workers, with Laws to protect us and unions to ‘help’ us. But back then, you had to be extremely strong, from a very young age, to go to work and ‘just get on with it’ in order to survive every day.

About the Creator

Ruth Elizabeth Stiff

I love all things Earthy and Self-Help

History is one of my favourite subjects and I love to write short fiction

Research is so interesting for me too

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.