Childhood is the first chapter in the book Lost Voices of the Edwardians by Max Arthur.

The difference between the Edwardian Era and the world we live in today, in 2025, can really be ‘seen’ through the experiences of these Edwardian children. At this time in history, there were no Laws to protect the children, and the NSPCC, (the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children), was in its infancy, (it was founded in 1884 as the London Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children).

‘Childhood’ was completely different to what we experience today, and these children had to grow up and look after themselves from a very early age. Whether rich or poor, children were expected to behave in a certain way. Those born into a rich family went to college, (usually the sons). The 'lower-class' sons and daughters left school at fourteen and were expected to go out to work at fourteen.

Here are their experiences in their own words:

Nicholas Swarbrick: “I was born in Grimsargh, Lancashire. My mother died quite early of tuberculosis. In those days Tuberculosis was incurable, and it was rampant. I was about four when she died, so I never really had a mother. I had one sister and a brother and my sister died of the same disease. She was in her late teens or early twenties. Of course, in those days, Consumption used to establish itself, then it became infectious, but it was not infectious in the early stages. It became infectious in my mother when I was about two, and for that reason we had to be kept away from her, which was a dreadful situation. I can remember having to keep some distance away on account of her coughing. So I never had the sort of mother where you could fly into her arms. That was the very thing I was never allowed to do. I didn’t know any different though.”

Fred Lloyd: “I was born on 23rd February 1898 at Copwood in Uckfield. There were sixteen of us in our family — I had eight sisters and seven brothers. My parents loved children. My mother died when she was forty-three I learned from one of my sisters that she died in childbirth. My father died soon after and they said it was from a broken heart.”

Jack Banfield: “In my family, there were seven children as well as Mum and Dad. Two of the children died as babies. That was very common. When you got over the age of about ten, you were past the post. Until then, there were measles, whooping cough, chicken pox, scarlet fever, so many diseases.”

What we very often forget is that this was a time when there were no antibiotics to fight against these childhood diseases. We still have them today, but with immunisations given to children at a young age, they are no longer ‘child-killers’, (thankfully). During the Edwardian Era, roughly 1 in 7 babies died in their first year.

Don Murray: “When I was at school, every class had at least two or three children who were knock-kneed, bow-legged or hump-backed. There was something wrong with at least three or four in each class.”

Rosamund Massy: “I shall always remember staying in a Salvation Army hostel in a shipping town in the North. Inside that house, run by a remarkable woman, there were many little girls living there for safety, having all been criminally assaulted. These poor little children were between eight and ten years of age and their little faces were heartbreaking. One of them told us that she had never had a toy in her life.”

Ronald Chamberlain: “I was brought up in a very strict environment. There was great strictness about table manners. No elbows on the table. Don't put food in your mouth when it's already full. Don't speak while you're eating. We always said grace before and had to ask permission to leave the table. Similarly, there were very strict rules in regard to the treatment of ladies. We had to open doors for them, let them go before us and walk on the roadside when they were out with us. The way we were dressed as children was very restrictive. At the age of five or six, I had a velvet suit with an elaborate lace collar, I can remember how uncomfortable it was.”

Ella Grace Hunt: “My mother used to keep a cane on the table, and if we didn't behave ourselves she said we would get ‘Tickle Toby’. That's what she called the cane — ‘Tickle Toby’. Well, for the most part we were very well behaved.”

Thomas Henry Edmed: “We lived in a millhouse on an estate owned by the chairman of the National Provincial Bank. Father was a labourer on the estate. He had been a colour sergeant in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. He was paid eighteen bob a week, from which he had to pay four bob rent. That left mum with fourteen shillings, for seven children. She had a hell of a time making this money go round. We used to get wood from the estate. We had a big brick oven and mother used to get flour in by the sack and she baked all her own bread. Father had a pension from the Fusiliers. He got seven pounds every three months, which would have helped, but the trouble was he used to spend most of it at the tavern.”

Dorothy Scorey: “Mother said we all had to have a trade, because she was left a widow when she was in her forties and she said that if we were ever left like her, you have to have something you can put your hand to. She was so blooming strict with us. ‘Any of my girls bring trouble home to me, the workhouses you'll go.’ That's what she used to say.”

Jack Brahms: “I was twelve when my mother died and after that I had to fathom for myself. Father couldn't do much for me. He might have made a meal at the weekend but most of my meals were a ha'p'orth of chips from Phillips, the fish and chip shop in Brick Lane. I'd sit on the doorstep and eat it. Or else, I'd go to the soup kitchen to get a can of soup and a loaf of bread. I used to go to McCarthy's lodging house because they had a fire burning there and I'd have a warm-up. I had to bring myself up.”

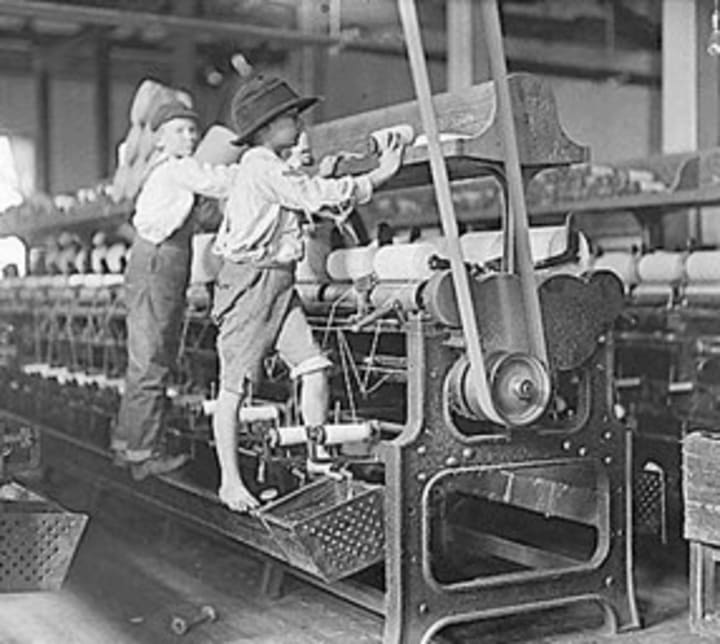

Harrison Robinson: “I went to Alder Street School until I was twelve. Then I went in the mill half-time, mornings one week and afternoons the week after, with school the rest of the time. The doctor had to pass you as fit when you went, but it was a bit of a farce. He came to the mill — everybody passed. We weren't tired at school when we were working half-time and we had no homework. But we had tests we had to pass. I was very good at sums and arithmetic. I left school when I was thirteen.”

Today, in 2025, most children leave school at sixteen, (I believe it's the Law now), and no child can start work under the age of sixteen and then they are only allowed to do certain hours, with nothing interfering with school. Thankfully the world has changed for children. During my reading of these experiences, there were too many children who left school at such a young age because it was expected that they bring money into the family budget. I don't think the parents were particularly ‘cruel’, it's just that was all they knew. The ‘class system’ between the upper class and lower class (the rich and the poor) did nothing to help the situation back then.

Polly Oldham: “I started work when I was twelve — half day at the mill, half day at school, then I went full-time when I was thirteen. Father was a great fellow — marvellous. He used to like a pint, but he’d do anything for his kids.”

Florence Hannah Warn: “When I was about ten, I did some housework for a crippled lady, scrubbing cement paths with a long-handled broom bigger than I, then scrubbing a long passage of linoleum and polishing it afterwards, black-leading a huge old-fashioned fireplace, scrubbing the floor cloth in the living room, and then scrubbing the scullery floor. It must have taken four or five hours. I was paid the princely sum of one shilling, but I had to hand it over to Mother, and received tu’pence for myself, but there was no feeling of resentment, as it was expected and quite usual.”

Again, we can see here that ‘it was expected’ that the children, even at such a such age, to go out and work and hand the money over into the family budget. In one way it taught the child how to work, handle money and budget, but — at such a young age. It begs the question, did the children ever play and ‘have’ a childhood?

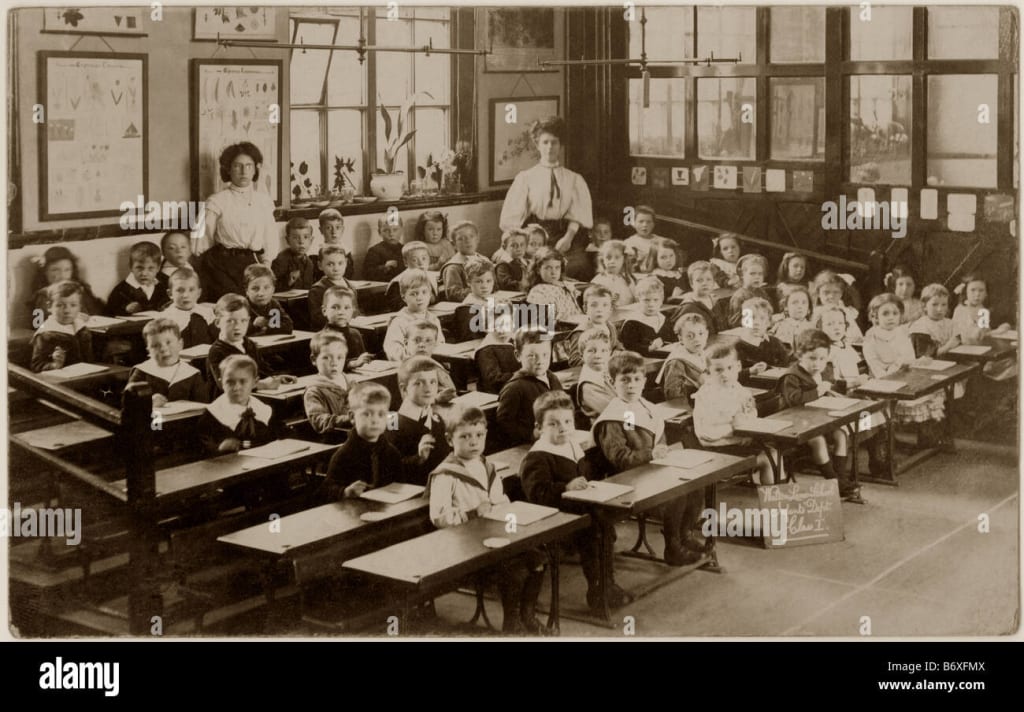

Fred Lloyd: “I was five years old when I started at Uckfield Holy Cross School. There were fifty children in the class. The school day started at nine and at twelve we had a break. Then we carried on until four. In the break, we played conkers, skipping, and football — except we used to kick a tennis ball because we didn’t have a proper football. I was pretty good most of the time, but the headmaster, Mr Richards used the stick on me once. I let a firework off in the cloakroom and it went off right outside his window. When he gave you the stick, he liked hitting you on the tips of your fingers where it hurt most.”

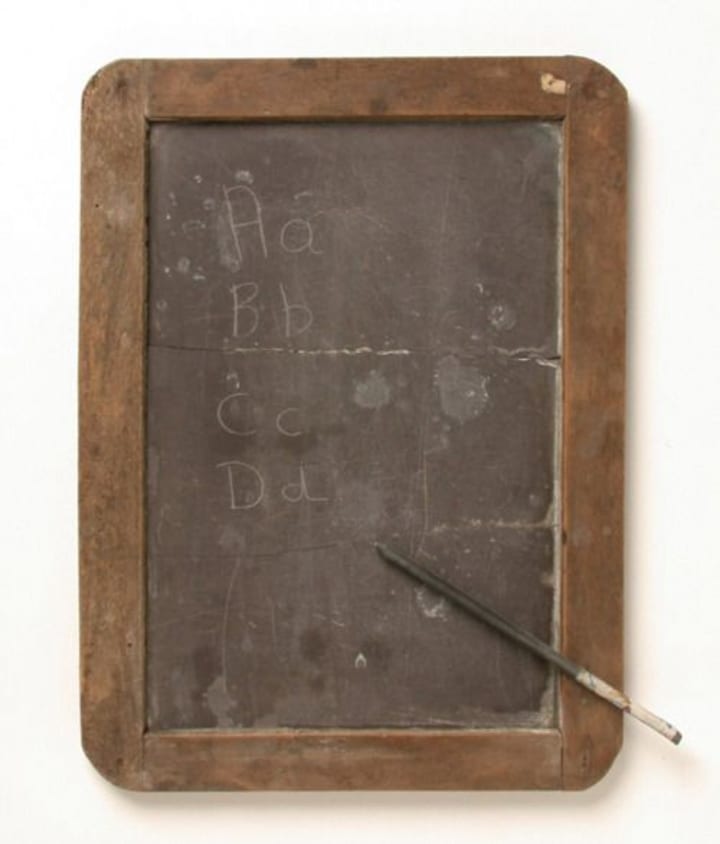

Jack Geddes: “Our teacher was Mr Rose. He lived at Chester-le-Street, and he used to come in on a little Douglas motorbike. He’d been in the Boer War. The slates we had were about twelve inches, bigger than the infants’ slates, and you had to buy your own slate. And you used to have a string fastened on so you could put it on your back, or inside your satchel. You did your homework on that. When you came back though, it might be raining, and if you had put your slate under your coat, it used to get rubbed off. If you put it in your satchel it was just the same. So you couldn’t protect it, it got rubbed or washed off, and when you got to school the next morning, it would be ‘Where’s your homework?’, ‘Sir, it was raining’, ‘It wasn’t raining where I was,’ and you got the cane. I thought that was very unfair.”

How completely different when compared to today’s schoolwork. Today, the children have digital tablets on which to do their homework, which can be saved and ‘never rubbed off’. When I was at school, it was all text books and notebooks, (which I still love). But in the Edwardian Era, there were no textbooks, notebooks or digital tablets, so the slate was the best the children had to do their homework on. It is amazing that they managed to learn anything using such basic equipment!

Albert ‘Smiler’ Marshall: “I was a bit of a fighter at school. A boy who had been expelled from another school started to cause problems in our class. The master took me aside and told me to deal with him, so I met him outside where he was bullying some of the smaller ones and I gave him a good beating. He was as right as rain after that and he wanted to be my friend, but I wasn’t having any of that.”

This is shocking to us today, but the proof is in front of us, this is a real life experience, absolutely true. We must be thankful that times have changed for our children in 2025.

Mr Patten: “When you got home you maybe got a meal or you had to wait until the father came in from his job. If you didn’t get a meal when you got in, you took off your school clothes, as you couldn’t afford to soil those, and you went and played outside. Well, there were apple trees, pear trees, and plum trees in your district somewhere, and you would have to get them some way or another. Everything like that was fair game, and it was always fair game to tease the keepers and those people who had apple trees and things. Even if we couldn’t eat them, it was a question of being clever enough to steal them from the owners. Your status would be improved if you were the one to steal the most.”

Many of the experiences were very similar, especially about school and going out to work at thirteen. We just cannot imagine doing this to our children today, but back then, it really was the norm. The fact that so many did make it to adulthood, shows the strength and courage that these children needed to simply get through every day. I must admit, I am glad I was born in a different time — at least I had a childhood and played and enjoyed my childhood years.

About the Creator

Ruth Elizabeth Stiff

I love all things Earthy and Self-Help

History is one of my favourite subjects and I love to write short fiction

Research is so interesting for me too

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.