Expectations influence whether a person feels "pain" or simply "stressed"

Celebrities reading

From toothaches, headaches, dysmenorrhea, muscle pain, to mental anguish, everyone is troubled by pain and tries to describe it with various metaphors. How have people’s perceptions and narratives of pain changed, from a “positive emotional experience” to an “evil” that needs to be defeated? Some people use this to show heroism, while others have no right to cry out pain; some people are considered to be naturally sensitive to pain, while others seem to be particularly pain-resistant - what causes these differences? How do people handle themselves when they are in pain?

Joanna Bourke, a professor of history at the University of London, tells the story of pain since the 18th century in her book "The Story of Pain", spanning various fields such as medicine, literature, religion, and biology, and examining people's understanding of pain. What changes have occurred in the story, and what impact have ideological factors such as belief, gender, race, class, etc., demonstrated the dynamic connection between the body, consciousness, culture, and language, and provided a new way for us to understand pain.

This article is excerpted from the introduction to the book "What is Pain?" ”, published by The Paper with the authorization of Guangqi Bookstore.

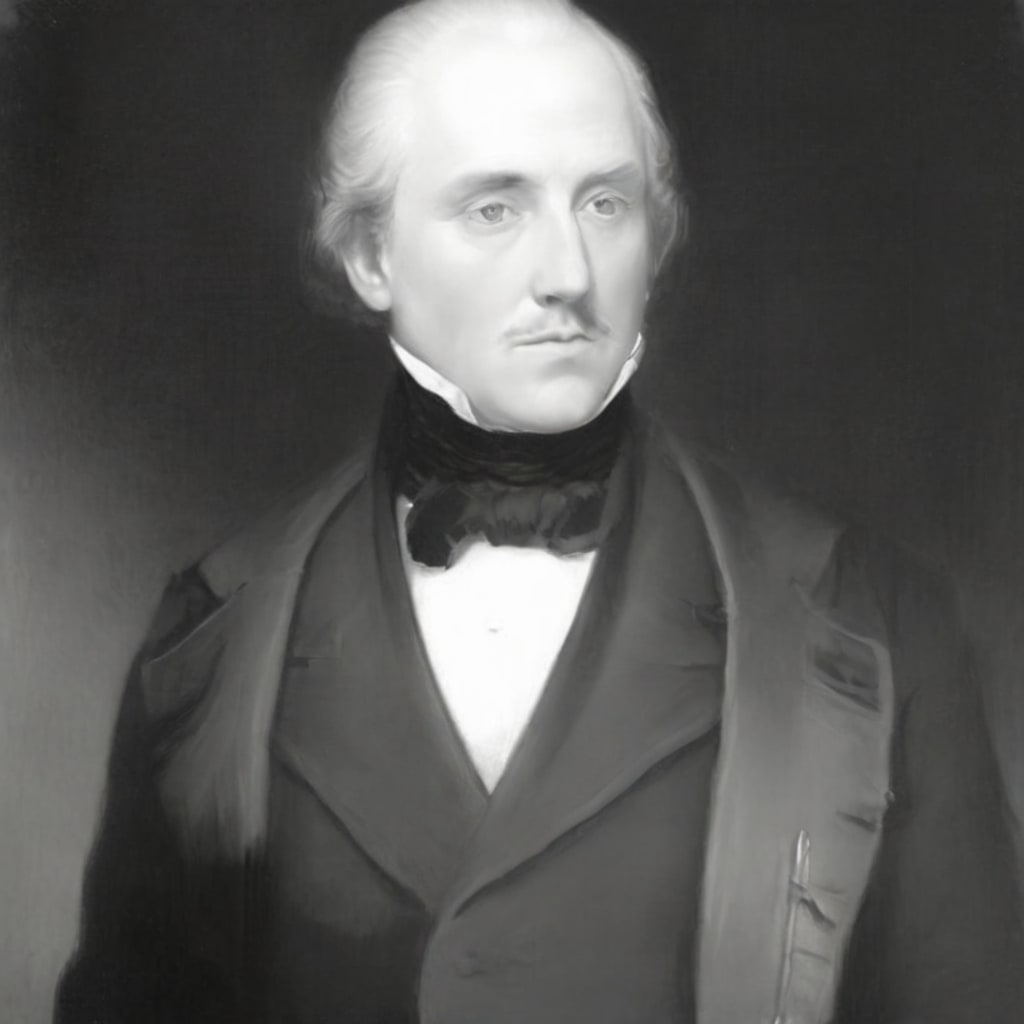

As I was writing this book, the voice of Dr. Peter Mere Latham repeatedly interrupted my thoughts. This surprises me: I have spent most of my life eavesdropping on the voices of women and the oppressed, minorities and the dispossessed. Yet the voice spoke to me with the confidence of a Victorian patriarch. Latham was born in London in the year of the French Revolution and died at the age of 86. One of London's most eminent physicians, he worked at Middlesex Hospital and later at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, where (like his father) he was appointed physician to the king. Latham is funny and loves to coach. He would occasionally admit his mistakes, but he was always confident in his own wisdom. Asthma attacks often disrupt his daily life. In the portrait, he is wearing a robe, his forehead looks majestic, his eyes are slightly confused, and he shows a confident smile: It is unimaginable that he would cry out in pain.

For me, however, Latham is most striking for his reflections on physical pain, published between the 1830s and early 1860s. Like me, he wanted to know the answer to this seemingly simple question: What is pain?

This problem is harder than we think. The English noun "pain" encompasses many very different phenomena. “Pain” is a label that can be applied to scraped knees, headaches, phantom limbs, and kidney stones. It is used for heart attacks and heartache. The adjective "pain" is very broad and can be used to describe a toothache, a boil, a burst appendix, or childbirth. Knives or hula hoops (as in a mini-epidemic among children in 1959, diagnosed as "Hula Hoop Syndrome" due to "excessive hula hoop playing") can cause pain. As Latham mused, pain comes in many guises. “There is a kind of pain that can barely interrupt a child’s self-satisfaction,” he points out, “and there is a kind of pain that even a giant cannot bear.” Are these two kinds of pain actually the same thing, just of different “degrees”? Is it true, he asks, that "the smallest pain encompasses everything that is essentially part of the largest pain, just as the smallest atoms of matter have the same properties as their largest aggregates." In everyday language, completely different pain experiences are expressed in one word - pain. But if we "pretend that we are at the bedside and that we can hear the real, haunting cry of pain," the similarity of the pain experience becomes clear: it is a mere verbal deception. “things of life and feeling”—that is, each person’s unique encounter with pain—and “everything else in the world is different.”

So, how did Latham manage to define pain? He claimed, somewhat impatiently, that the correct response to anyone who asked "what is pain" was to simply point out that "he himself knew exactly what it was" and that "no matter what words he used to define it, no one could know better. many". Latham emphasized this point, insisting:

What all men understand unmistakably through their own perceptual experience cannot be expressed more clearly in words. So let’s simply call pain pain.

Latham's definition of pain—what we call "pain"—is shared by many historians, anthropologists, sociologists, and even clinicians. Anyone who claims "pain" is in pain; anyone who uses "pain" to describe her experience is in pain. For the purposes of historical analysis, as long as someone is said to be in pain, the claim will be accepted. In Latham's words, "the fact of suffering pain must always be based on the patient's own presentation," on the grounds that "everyone suffers from his own pain." Of course, like Latham, we might admit that "there is such a thing as feigning pain," but this would not change our primary definition.

This method of managing pain has yielded huge results. It fits well into the way many historians approach their research and is completely respectful of the way people in the past created and recreated their lives. It makes possible multiple (even conflicting) descriptions of pain. It does not impose judgments on how people in the past (or today) should describe pain (whether clinically, politically, in terms of lived experience, or in any other way). It maintains polite neutrality regarding the truth of any specific assertion. Crucially, this definition allows us to problematize and historicize all components of the “talk of pain.” It allows us to explore how the label “pain” changes over time. It insists that “pain” is constructed by many discourses, including theological, clinical, psychological, and others. Done poorly, it assumes that "pain" can be transparently "read" from various texts; yet, done well, this approach to pain encourages subtle and deconstructive explorations of past experiences and actions. analysis.

I understand this approach: it is part of the pragmatist and anti-essentialist turn within cultural history, and I find it helpful. I also appreciate the way Latham points to it, which predates the popularity of Foucauldian “social constructionism” by more than a century. In fact, much of my previous historical writing was explicitly based on the following premise: Historically, class, violence, fear, rape, humanity (to name a few examples from my work) are all constructed within disjointed traditions. of. I'm still not happy to give up on this premise.

However, the definition of pain encounters significant limitations. The clue to the problem is that when Latham refers to "pain," he often capitalizes it: for him, pain is pain. In other words, there is a premise: pain is an “it,” an identifiable thing or concept. To be fair, Latham was aware of the problem. He is not convinced that "pain" is "it" and excuses himself by saying that his materialization of "pain" (although he would not use the word himself) is driven by actual observation. He noted that "whoever has suffered pain, smart or stupid, endows it with a quasi-materialism." In the struggle of severe physical pain, even the most rational philosopher will find that "their feelings make no sense." “I know quite a few philosophers,” Latham continued, “who like to evaluate and blame their own pain as if it were an entity or separate entity in itself.” So he points out:

For practical purposes, we must often reach a compromise between philosophy and common sense by asking people to think and talk about [pain] as it appears to be rather than as it is. We have to get them talking about pain this way. Nothing can be done.

Latham's condescending tone may give us pause, but his basic point is sound. People who are in pain are qualified to say, "I don't know what you mean by pain, but I know 'it' when I feel 'it.'" and then go on to describe their pain as if it were inside their body. an independent entity ("I have a toothache") or an entity attacking from outside (for example, pain is a stinging weapon, a burning fire, a biting animal). However, for historians who sit down to write a history of pain, to assume that pain has a clear ontological existence is to conflate sensory presentation with linguistic representation.

At the very least, it is useful to point out the danger of treating pain as an entity: it risks turning "pain" into an independent subject. How easily we make this mistake is demonstrated by a look at one of the most influential books on pain of the 20th century: Elaine Scarry's The Body in Pain (1985). Scarry pointed out that pain lies beyond words, is absolutely private and cannot be communicated. In fact, in one of his most frequently cited claims, Scarry goes even further, insisting:

Physical pain not only resists language but actively destroys it, immediately returning the person to the state before language, the state of making sounds and crying before language was learned.

This is an extreme version of physicalizing pain. As literary scholar Geoffrey Galt Harpham rightly observed:

[Such claims] treat it as an immediate, single physical experience, a baseline of reality, when in fact it is a combination of feelings, personality, cultural environment, and interpretations, a process that encompasses body, mind, and culture. Phenomenon. In other words, precisely by attributing a quality to pain, treating it as a fact (the hard truth, the first and last fact) rather than as an explanation, she misunderstood its quality.

In other words, Scarry fell into the trap of treating metaphorical ways of conceiving pain (pain bites and stings, it dominates and conquers, it is terrifying) as descriptions of real entities that exist. Of course, pain is often treated metaphorically and becomes a separate entity within the human body, but Scarry took these metaphors literally. It is the “pain” that is given agency, not the person who endures the pain. This is an ontological fallacy.

As I argue next, by thinking of pain as an “event type,” we can avoid falling into Latham and Scarry's ontological trap. Painful events always belong to an individual's life and are part of his life story.

What do I mean when I say pain is an event? By specifying pain as an "event type" (I'll explain what "event type" means in a moment), I am saying that it is one of those recurring events that we often experience and witness, engaging the "self." ” and the construction of consciousness of the “other.” An event is called "pain" if it is identified as "pain" by a person who claims to have such a perception. "Being in pain" requires the individual to give meaning to this particular "type" of existence. I use the word "meaning," not in the sense of "importance" (the pain may be a brief pinprick), but in the sense of "awareness" (it's a tummy ache, not a growl before lunch). Pain is never neutral or objective (even people who have had lobotomies, and therefore lack emotional anxiety about pain, still perceive the physical imprint of what they call pain). In other words, painful events have what the philosopher Paul Ricoeur calls “mine-ness” (albeit in a different context). In this way, through the process of naming, one becomes or makes oneself into a pain-bearer.

I said earlier that the individual needs to name the pain - he needs to identify it as a unique event in order to label it a "painful event." However, how does one know what to name pain? If the words we use to describe feelings are personal or subjective, how do we know how to identify them? How do we label one feeling "pain" but not another?

In recent years, scholars exploring feelings have turned to the ideas of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. In Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein turns his attention to the question of whether there is such a thing as a private language. "How do words refer to feelings?" he asked. Like Latham, he acknowledges that people talk about their feelings every day. As Wittgenstein said, "Don't we talk about sensations every day and give them names," so why all the fuss? Simply put, he continued:

How is the connection between names and things established? This question amounts to: How does one learn the meaning of a sensory name? For example, the word "pain".

Wittgenstein, dissatisfied with the solid and immutable theories assumed by philosophers, humbly proposed "a possibility":

Words are associated with primitive, natural expressions of feeling and are used in their place. A child hurts himself and he cries; then an adult talks to him and teaches him interjections, followed by sentences. They taught the child new pain-behaviors.

He imagined an interlocutor interrupting him and asking: "So you're saying that the word 'pain' really means crying?" "On the contrary," Wittgenstein continued, "the verbal expression of pain takes the place of Crying, there’s no describing it.”

Imagine, he mused, a world where there were no outward expressions of feeling, like no one crying or making faces. How do others know he is in pain? This person may scribble an "S" in their journal every time they experience a particular feeling. But how does he know that every experience he experiences feels the same? How does anyone know what the "S" means? This diarist has no criteria for judging when he has experienced "S" and when he has experienced "T". To be meaningful, Wittgenstein concluded, a word like "pain" that denotes a sensory state must be intersubjective and therefore capable of being learned. In other words, the naming of a “pain event” is never entirely personal. Although pain is usually seen as a subjective phenomenon - it is "personal", "naming" appears in the public domain.

Wittgenstein obviously liked to imagine other worlds. On another occasion, he invented a world in which everyone had a box containing a beetle. However, no one is allowed to peek into other people's boxes. Since everyone can only tell what a beetle is by looking at their own box, it makes perfect sense for everyone to assume that "beetle" refers to an entirely different entity. In fact, the "beetle in the box" may change frequently. The box may even be empty. However, if everyone believes that they have a "beetle in the box," then the word "beetle" will work in communication. In other words, when it comes to language, the "actual contents" of the box don't really matter. What matters is what role the “beetle in the box” plays in terms of public experience.

Now replace the word "beetle" with "pain": I don't have direct access to your subjective consciousness, and that doesn't matter, as long as we have a common language to discuss various kinds of "pain." Wittgenstein's language games draw attention to a way of dealing with pain that may be very useful to historians. As he succinctly puts it: "Psychological language is profound not because of its ability to reveal, mark, or describe mental states, but because of its function in social interaction." For historians, then, it is important is to interrogate the different language games played by people living in the distant "past" in order to allow us to make educated guesses about the various unique ways in which people packaged "beetles in boxes."

I believe it is helpful, for reasons I will give later, to conceptualize pain as an event made public through language. Yet my approach to pain also suggests that pain is an “event type.” What I mean is that it is helpful to understand pain events in terms of adverbials. For example, there is a difference between saying "I felt a sharp knife" and "I felt a sharp pain." In the first case, the knife is what linguists call an "alien accusative" (that is, the knife refers to the object of the sentence); in the second case, the pain is an "alien accusative" (it Modifies the verb "feel" rather than being the object of perception itself). As the philosopher Guy Douglas said, in the first sentence, we "describe the knife, not the sensation; when we say the pain is sharp, we describe the sensation." That is, a perception similar to being scratched by a sharp object. In other words, when we say "I felt sharp pain," we are modifying a verb, not a noun.

Another way to put it is that pain describes the way we experience something, not what is experienced. It is a way of feeling. For example, we say that a toothache hurts, but "pain" is not actually a property of the tooth, but the way we experience or perceive the tooth (this is similar to saying that a tomato is red: "redness" is not a property of the tomato, but a property of our perception of the tooth). tomato way). In Douglas's words, "Sensory properties are properties of the way we perceive objects (rather than of the objects themselves)." Pain is “not a thing or object that someone feels, but what it feels like to feel that thing or object.” The point is that pain is not an inherent quality of a natural sensation, but a way of perceiving the experience. Pain is a pattern of perception: pain is not the trauma or noxious stimulus itself, but the way we evaluate the trauma or stimulus. Pain is a way of being in the world, or a way of naming events.

The historical question then becomes: How do people respond to pain, and what ideological work do pain behaviors strive to accomplish? By what mechanism do these event types change? As an event type, pain is an activity. People cope with pain in different ways. Pain is practiced within relevant environmental contexts, and there are no out-of-context pain events. After all, screams caused by so-called "noxious stimuli" can be painful (corporal punishment) or full of fun (masochism). The severity of tissue damage is not necessarily proportional to the amount of pain experienced, because a wide variety of phenomena—fighting enthusiasm, job satisfaction, spousal relationships, the color of painkillers—can determine the amount of pain experienced. Expectations can influence whether a person feels "pain" or simply "stressed." One can easily use the same word "pain" to refer to a flu shot and an ocular migraine.

Although we have all been immersed in a culture of pain since birth, being in pain is anything but static or monolithic, which is why it requires a history. People can and often do challenge dominant conceptions of pain. Indeed, the creativity surrounding pain is quite astonishing, and some people in pain use it for language games, environmental communication, and physical performances (including gestures). Of course, as we will see in this book, the most mainstream "action" with pain is to reify it into an entity - to give it an autonomy, independent of the agent of pain. It therefore becomes important to ask these questions: Who determines the ontological content of any unique, historically specific, geographically located ontology? What is excluded from these acts of power?

Much of the book leaves "people to think and talk about things as they appear to be," as Latham expresses it: Think of pain as an "it," or something to be listened to, obeyed, fought against entity. However, ways of being in pain involve a range of subjects, immersed in complex relationships with other bodies, environments, and linguistic processes. It would be disingenuous to say that Latham fully agrees with my point of view, but I like to imagine that when he spoke these words shrewdly, he was expressing such a position:

Pain itself is a part of life and can only be tested by its impact on life, its function in life. Regardless of whether it is small or large (figuratively speaking) or to what extent it is, we must look at its impact and function in life.

Translated into my own language game, pain is always a state of "being in pain" that can only be understood through the way it disrupts and alerts, validates and cultivates one's "state of being" in the real world.

About the Creator

xx x

Hello everyone, I am a new all-around writer. I will share with you what is happening every day about the earth, country, environment, food, health, etc. Thank you for watching.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.