The Status of Music in Early Islamic Society: The Era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs

This study examines the status of music in Islamic society after the Prophet, during the era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs.

The Status of Music in Early Islamic Society: The Era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs

Author: Islamuddin Feroz, Former Professor, Department of Music,

Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Kabul

Abstract

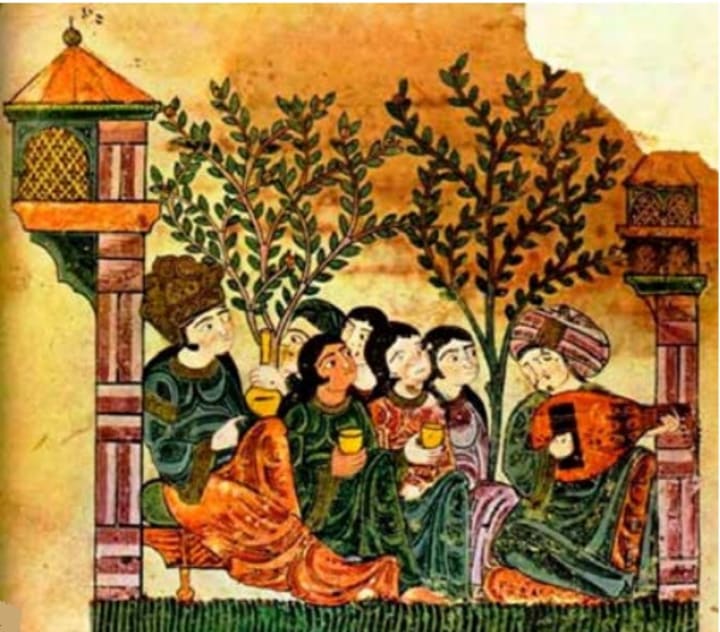

The era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs (632–661 CE) represents one of the most sensitive periods in Islamic history in terms of the formation of religious, cultural, and social attitudes. Music during this period occupied a dual position: on one hand, it was part of the legacy of pre-Islamic Arabia, and on the other hand, it was a moral and religious concern, with some considering it mere frivolity. During the caliphates of Abu Bakr and Umar, due to personal asceticism and the prevailing military and political conditions, musical activity was limited, and music was mostly seen in the forms of hada’, nasheed, and Quranic recitation. In the era of Uthman and Ali, with the expansion of urbanization and the emergence of aristocratic classes, music regained popularity in private spaces. This study examines social conditions, religious attitudes, and musical performance practices during the era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs through an analysis of historical texts and early reports, showing that despite religious and moral restrictions, the necessary foundations for the development of music as an art and science in subsequent centuries were laid.

Keywords: Early Islam, Rightly Guided Caliphs, Arabic Music, Ilm al-Musiqa, Islamic Culture, Qinat, Hada.

Introduction

The era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs, including the caliphates of Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali (may God be pleased with them), was not only a stage of political and religious consolidation of Islam but also a transitional period from the oral culture of pre-Islamic Arabia to a new moral and devotional system. In this transformative context, music, as one of the manifestations of the earlier culture, assumed a complex and ambiguous position. On the one hand, the Qur’an and the prophetic tradition emphasized moderation in pleasures and avoidance of frivolity; on the other hand, song and melody were inseparable parts of Arab cultural life. During Abu Bakr’s caliphate, the spirit of asceticism and avoidance of frivolity limited artistic activities. With the beginning of Umar’s caliphate and the extensive conquests, cultural contact with Khorasan, Persia, and Byzantium increased, but music had not yet attained a public or official status. In Uthman’s era, the presence of qinat and court music in Medina became more prominent, and during Ali’s caliphate, the conditions for cultural and musical diversity became clearer. Examination of these four periods shows that although music was restricted at the official level, it persisted in social and family life and ultimately laid the groundwork for the development of Ilm al-Musiqa. This article, through an analysis of historical sources and musical performance practices, demonstrates how the limitations and opportunities during the era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs provided the conditions for the growth of music and the establishment of its scientific foundations.

Music at the Beginning of the Era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs

With the death of the Prophet in 632 CE, Muslims chose Abu Bakr as the Caliph (“successor”). The next three caliphs were also elected by the Muslims: Umar (634 CE), Uthman (644 CE), and Ali (656 CE). Immediately following the Prophet’s death, Arabia experienced division and discord. False prophets appeared in various regions, and different tribes, from distant Oman to the outskirts of Medina, the capital of Islam, openly rebelled against the caliphate and apostatized from Islam. Nevertheless, in less than a year, these wayward groups returned to the political and religious framework of Islam. To achieve this, large armies were mobilized, and the spirit of fighting the nonbelievers reached its peak. Between 633 and 643 CE, Babylon, Mesopotamia, Syria, and Egypt were attacked and conquered, an event of significant cultural importance for the future of Islamic civilization (Farmer, 1992, p. 39).

The days of the caliphate of the four Rightly Guided Caliphs, recognized as the “True Caliphs,” represented a stringent period in Islam. During this era, Islamic law, as established by the Prophet or interpreted by his Companions, was enforced rigorously. Music was prohibited. Ibn Khaldun, the greatest Muslim historian, notes that at the dawn of Islam, anything inconsistent with the teachings of the Qur’an was despised, and singing and theatrical performances were banned. The first two caliphs likely had little interest in music and were indifferent toward it. They certainly did not have much opportunity to focus on the arts due to ongoing wars and the effort to consolidate Islam. They themselves led the simplest of lives and expected others to do the same. They recognized that the arts could not be practiced without luxury, or even extravagance, both of which were condemned by these caliphs.

The Era of Abu Bakr ibn Abi Quhafa (632–634 CE)

During the caliphate of Abu Bakr al-Siddiq (may God be pleased with him), which lasted approximately two years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), the Islamic community was at a critical stage of political, religious, and social consolidation. At this juncture, the primary priority of the caliphate was not the development of cultural or artistic activities, but the preservation of the unity of the Muslim community, the prevention of tribal apostasy, and the strengthening of the foundations of the nascent Islamic system. Consequently, the social and cultural life of Muslims took on the character of asceticism, simplicity, and caution, and any manifestation of luxury or entertainment was viewed with suspicion. Some scholars believe that during Abu Bakr’s time, music was considered among the malahi or “forbidden pleasures” and was not endorsed by the government or religious authorities. However, early historical sources provide no direct evidence of an official decree or prohibition of music during this period; such perceptions derive more from the cultural, moral, and ascetic environment of his era.

It appears that the early Muslim society, which had only recently distanced itself from the pre-Islamic Arab traditions of poetry and song, was still in the process of redefining the role of music in its religious and social life. It is likely that qinat and qiyariyya (female singing slaves) living in the households of the aristocracy and wealthy families were not significantly disturbed, as their activities were confined to private circles and did not directly interact with the broader public. They sang for the amusement of their masters and played simple instruments such as the mizhar and daf. In contrast, public musicians and tavern performers, who operated in open spaces, likely faced moral and social pressures or at least lost the courage to continue their work (Ibid, 1992, p. 39).

During this period, music had not yet emerged as an independent “science” or “art” in the manner later recognized as Ilm al-Musiqa. What appeared in Islamic society in terms of melody and song was mostly in the forms of hada’ (camel-herding and martial chants), nasheed (religious and heroic hymns), and Quranic recitation. Abu Bakr himself was an ascetic, pious, and strict figure in worldly matters, avoiding any manifestations of luxury; thus, the general social environment, following his example, also distanced itself from music and adopted a cautious attitude toward it (Reynolds, 2017, p. 211).

The Era of Umar ibn al-Khattab (634–644 CE)

Nevertheless, days with relatively greater freedom were ahead. Umar (634–644 CE) seems to have differed little from his predecessor in this respect. According to a hadith from Aisha, Umar once heard the voice of a singing slave-girl in the Prophet’s house. This may have inclined him, at least to some extent, toward the songs of female singers. It is also said that he was uneasy with the idea of the Qur’an being recited in anything other than melodious intonation. His son, Asim, had a keen interest in music, and one of the caliph’s governors, named Nu’man ibn ‘Adi, who was in charge of Maysan, was certainly a patron of the arts. There is a report that one day Umar heard the sound of a tambourine outside his house. When he asked what it was, he was told it was a celebration for a circumcision, and it is explicitly mentioned that the caliph remained silent. The author of Al-Aghani notes: “It has been said that Caliph Umar composed a melody, though this is less likely.” Perhaps historians confused him with Umar II (717–720 CE), who was certainly a composer. Nonetheless, Ibn Hajar and Ibn Durayd claimed that Umar I was a poet (Farmer, 1992, p. 41).

The Era of Uthman ibn Affan (644–656 CE)

During Uthman’s caliphate, broad economic and social transformations took place. Prosperity in trade, the expansion of conquests, and the increase in general wealth allowed a more prominent place for luxurious living and the fine arts. Unlike his predecessors, Uthman had a greater inclination toward display and comfort, and during his reign, music flourished in the cities of the Hejaz, Mecca, and Medina. In particular, the presence of slaves and war captives from various regions brought cultural diversity. Many of these captives, being musicians and singers, introduced their own traditions and instruments, gradually fostering innovation in Arabic music (Hatter, 2015, p. 2679).

At the same time, a class of professional musicians emerged, largely from among freed slaves (mawali). The first professional male musician in Islamic history is considered to be Tuwaiys, who gained fame in the late period of Uthman’s caliphate. Born in Medina, he performed Arabic music with iqaa (rhythmic patterns). Al-Aghani refers to him as the first person to introduce structured music with rhythmic measures in Medina. Tuwaiys performed exclusively with the daf, and his student Ibn Suraij regarded him as the greatest master of the hazaj rhythm. Alongside him, ‘Izza al-Mila, one of the first prominent female musicians, gained considerable fame. She was a student of pre-Islamic singers such as Ra’iqa and Salma and played instruments such as the mizhar, ma’azifah, and oud. By reinterpreting ancient Arab songs, ‘Izza combined pre-Islamic music with an Islamic aesthetic. Simultaneously, musicians such as Sa’ib Khathir, who initially played the qadhib (a rhythmic staff) and later moved to the oud, elevated Arabic music from its primitive form to a more artistic framework. He is said to have been the first to accompany his singing with the oud (Farmer, 1992, pp. 45–47, 52).

The Era of Ali ibn Abi Talib (656–661 CE)

Ali himself was a poet and the first caliph to offer open and genuine support for the fine arts and literature, permitting the study of sciences, poetry, and music. Despite the continued conservative religious outlook in society, his patronage of knowledge and culture enabled music—particularly in the Hejaz—to emerge from its initial stagnation. During this period, the aristocracy and prominent families also became supporters of music, including Aisha (the Prophet’s wife), Sukayna bint al-Husayn, and Abdullah ibn Ja’far ibn Abi Talib. Abdullah ibn Ja’far, being from the Prophet’s family, was himself a musician and lover of music, supporting female musicians such as ‘Izza al-Mila and Jamila (Ibid, 1992, pp. 45–47).

The caliphate of Ali ibn Abi Talib (656–661 CE) was characterized by absolute support for literature and the arts. Musical sciences were taught alongside other sciences and literature. During this period, a new type of singing called al-Mutqin (masterful singing) emerged. Initially, professional musicians were freed slaves. The Mutqin singing had its own independent rhythm, separate from the poetic meter. Among the most famous musicians of this period were Amr ibn Umayya al-Dhammari, who played the tanbur at Ali’s wedding and was regarded as a master of the instrument, and Hamza al-Yatimiya, who sang at the same wedding and was a leading vocalist of the era (Muaydi, 2021, p. 172).

One of the musicians of his era, Ahmad al-Nasibi, or Ahmad ibn Usama al-Hamdani from Kufa, was a master of a type of singing called Nasb, through which serious music was introduced. He is considered the first recognized tanbur (pandura) player of the Islamic period (Farmer, 1992, pp. 54–57). By the end of the era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs, a more artistic style of music called Ghina’ al-Mutqin was introduced, characterized by the use of a single iqaa or rhythm for the melody of the song, independent of the poetic meter (Ibid, 1992, pp. 47–49).

In the first decades of Islam, very few Arab men were “professional musicians,” meaning they performed publicly for monetary gain. Nevertheless, many had attained a high level of musical understanding and performance in private settings (Reynolds, 2021, p. 34). Early in the caliphal era, singers and musicians played little role in the courts, but over time, the Arab elite became enthusiastic patrons of musicians and singers. Gradually, the caliphs became acquainted with music and instructed civil and military officials to use music even in battles, with some units reportedly employing hundreds of trumpets and drums, the only instruments known for military music at the time (Zaydan, 1993, p. 141).

Despite differing views, music managed to free itself from the social and religious prohibitions that had constrained it. This was largely due to the interest shown by the upper classes and, to some extent, the old musical traditions of Medina, whose Ansar inhabitants had always loved singing, a fact even acknowledged by the Prophet himself. Significant technical progress in the art of music was achieved for several reasons: new ideas introduced through fresh cultural contacts, the emergence of a professional class of male musicians, and the strong interest in music from the highest social strata, which stimulated technical advancements to meet the new demands created by poetry.

Musical instruments during this period were also highly varied. String instruments included the mizhar (skin-covered oud), oud (wooden oud), ma’azifah (harp), and tanbur (pandura). Wind instruments included the shababa flute, horizontal flute (mizmar), and trumpet (būq). Percussion instruments such as the daf, qadhib (rhythmic staff), and drum were widely used. These instruments often accompanied singing in various ceremonies, and their combination in courtly music was also likely (Klein, 2023, p. 13).

Conclusion

The findings indicate that music during the era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs played a complex role and was influenced by political, religious, and cultural factors. Ethical and religious restrictions under Abu Bakr and Umar prevented music from achieving public or official prominence, confining it largely to religious and traditional melodies. However, the eras of Uthman and Ali demonstrated that with the support of the aristocracy and attention to cultural life, music could grow and develop into more diverse forms. In other words, this period laid the groundwork for music to become not merely a recreational activity but an art with defined social and cultural structures, paving the way for the development of Ilm al-Musiqa in later centuries.

Analysis of this era shows that despite religious and moral restrictions, music persisted in social and private spheres, aligning with cultural, political, and social needs. This interaction between religious attitudes, ethical values, and cultural realities facilitated the establishment of music as both an art and a theoretical science (Ilm al-Musiqa) in subsequent periods. The era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs not only facilitated the transmission of pre-Islamic Arab musical heritage into Islamic society but also laid the foundations for theoretical and practical musical development, including instruction, instrumental performance, execution styles, and the creation of a professional class of musicians. This conclusion demonstrates that music in early Islamic society, despite limitations, played a significant role as a dynamic cultural phenomenon in shaping art, education, and music theory in later centuries, making the study of this period crucial for understanding the interplay of religion, culture, and art in Islamic history.

References

Farmer, Henry George. (1930). Historical Facts for the Arabian musical influence. London: William Reeves 83 chasing Cross Road, Bookseller Limited.

Farmer, Henry George. (1992). A History of Arabian Music. London: Luzac & co.

Hattar, Renee Hanna. (2015). Music and Interfaith Dialogue: Christian Influences in Arabic Islamic Music. International Center for the Study of Christian Orient, Granada, Spain. Middle East Journal of Scientific Research 23 (11): 2676-2682, 2015 ISSN 1990-9233 © IDOSI Publications.

Klein, Yaron. (2023). Musical Instruments in Samāʿ Literature: al-Udfuwī’s Kitāb al-Imtāʿ bi-aḥkām as-samā. Carleton College, Northfield, MN, United States. Oriens (2023) pp 1–24.

Muaydi, Anis Hammoud. (2021). The Journey of Music and Singing from Babylon to Baghdad: An Introduction to the Development of Iraqi Music. A Peer-Reviewed Scientific Quarterly Journal First Issue Published in April 2008 Issue No. 54 – Summer 2021. Pp 150-164.

Reynolds, Dwight F. (2021). The Musical Heritage of Al-Andalus. New York: published by Routledge. Reynolds, 2021, P 24

Reynolds, Dwight F. (2017). Song and Punishment. koninklijke brill nv, leiden. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004343290_012

Zaydan, Jurji. (1993). History of Islamic Civilization. Translated by Ali Javaherkalam. Tehran: Amir Kabir Publishing.

About the Creator

Prof. Islamuddin Feroz

Greetings and welcome to all friends and enthusiasts of Afghan culture, arts, and music!

I am Islamuddin Feroz, former Head and Professor of the Department of Music at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Kabul.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.