In 2019, Rap music was ranked the most popular genre overthrowing the long-time holder, Rock. (According to Nielsen's Year End Report) Its status has remained the same.

As a writer, I want to get to the bottom of why that is.

ROOTS OF RAP

By Brian Salkowski

A book of rhymes is where MCs write lyrics. It is the basic tool of the rapper's craft. Nas raps about "writin' in my book of rhymes, all the words pass the margin." Mos Def boasts about sketching "lyrics so visual / They rent my rhyme books at your nearest home video." They both know what Rakim knew before them, that the book of rhymes is where rap becomes poetry.

Every rap song is a poem waiting to be performed. Written or freestyled, rap has a poetic structure that can be reproduced, a deliberate form an MC creates for each rhyme that differentiates it, if only in small ways, from every other rhyme ever conceived. Like all poetry, rap is defined by the art of the line. Metrical poets choose the length of their lines to correspond to particular rhythms-they write in iambic pentameter or whatever other meter suits their desires. Free verse poets employ conscious line breaks to govern the reader's pace, to emphasize particular words, or to accomplish any one of a host of other poetic objectives. In a successful poem, line breaks are never casual or accidental. Rewrite a poem in prose and you'll see it deflate like a punctured lung, expelling life like so much air.

Line breaks are the skeletal system of lyric poetry. They give poems their shape and distinguish them from all other forms of literature.

Rap is poetry, but its popularity relies in part on people not recognizing it as such. After all, rap is for good times; we play it in our cars, hear it at parties and at clubs. By contrast, most people associate poetry with hard work; it is something to be studied in school or puzzled over for hidden insights. Poetry stands at an almost unfathomable distance from our daily lives, or at least so it seems given how infrequently we seek it out.

This hasn't always been the case; poetry once had a prized place in both public and private affairs. At births and deaths, weddings and funerals, festivals and family gatherings, people would recite poetry to give shape to their feelings. Its relative absence today says something about us- our culture's short attention span, perhaps, or the dominance of other forms of entertainment-but also about poetry itself. While the last century saw an explosion of poetic productivity, also marked a decided shift toward abstraction. As the poet Adrian Mitchell observed, "Most people ignore most poetry / because most poetry ignores most people."

Rap never ignores its listeners. Quite the contrary, it aggressively asserts itself, often without invitation, upon our consciousness. Whether boomed out of a passing car, played at a sports stadium, or piped into a mall while we shop, rap is all around us. Most often, it expresses its meaning quite plainly. No expertise is required to listen. You don't need to take an introductory course or read a handbook; you don't need to watch an instructional video or follow an online tutorial. But, as with most things in life, the pleasure to be gained from rap increases exponentially with just a little studied attention.

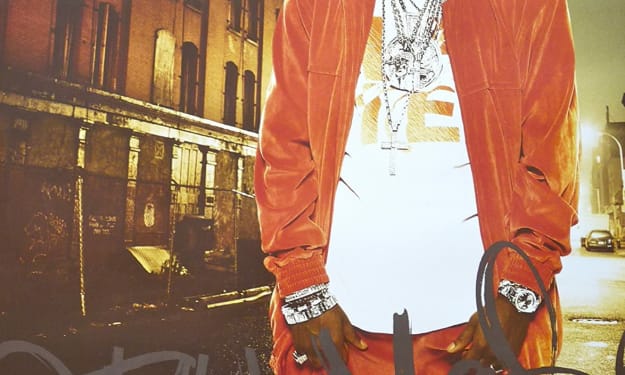

Hip hop emerged out of urban poverty to become one of the most vital cultural forces of the past century. The South Bronx may seem an unlikely place to have birthed a new movement in poetry. But in defiance. of inferior educational opportunities and poor housing standards, a generation of young people-mostly black and brown-conceived innovations in rhythm, rhyme, and wordplay that would change the English language itself. It Can't Stop, Won't Stop: A History of the Hip Hop Generation, Jeff Chang vividly describes how rap's rise from the 1970s through the early 1980s was accompanied by a host of social and economic forces that would seem to stifle creative expression under the weight of despair. "An enormous amount of creative energy was now. ready to be released from the bottom of American society," he writes, "and the staggering implications f this moment eventually would echo around the world." As one of the South Bronx's own, rap legend KRS One, explains, "Rap was the final conclusion of a generation of creative people oppressed with the reality of lack."

Hip hop's first generation fashioned an art form that draws not only from the legacy of Western verse but from the folk idioms of the African diaspora; the musical legacy of jazz, blues, and funk; and the creative capacities conditioned by the often harsh realities of people's everyday surroundings. These artists commandeered the English language, the forms of William Shakespeare and Emily Dickinson as well as those of Sonia Sanchez and Amiri Baraka, to serve their own expressive and imaginative purposes. Rap gave voice to a group hardly heard before by America at large, certainly never heard in their own often profane, always assertive words. Over time, the poetry and music they made would command the ears of their block, their borough, the nation, and eventually the world.

Rap is an oral poetry, so it naturally relies more heavily than literary poetry on devices of sound. The MC's poetic toolbox shares many of the same basic instruments as the literary poet's, but it also includes others specifically suited to the demands of oral expression. These include copious use of rhyme, both as a mnemonic device and as a form of rhythmic pleasure, as well as poetic tropes that rely on sonic identity, like homonyms and puns. Add to this those elements the MC draws from music tonal quality, vocal inflection, and so forth and rap reveals itself as a poetry uniquely fitted to oral performance.

Early pop lyricists like Cole Porter and Lorenz Hart labored over their lyrics; they were not simply popular entertainers, they were poets. Great MCs represent a continuation and an amplification of this vital tradition of lyric craft. The lyrics to Porter's "I've Got You Under My Skin" are engaging when read on the page without their melodic accompaniment; the best rap lyrics are equally engrossing, even without the specific context of their performances. Rap has no sheet music because it doesn't need it-rapping itself rarely has harmonies and melodies to transcribe but it does have a written form worth reconstructing, one that testifies to its value, both as music and as poetry. That form begins with a faithful transcription of lyrics.

Rap lyrics are routinely mistranscribed, not simply on the numerous websites offering lyrics to go, but even on an artist's own liner notes and in hip-hop books and periodicals. The same lyric might be written dozens of different ways-different line breaks, different punctuation, even different words. The goal should be to transcribe rap verses in such a way that they represent on the page as closely as possible what we hear with our ears.

Transcribing rap lyrics is a small but essential skill, easily acquired. The only prerequisite is being able to count to four in time to the beat. Transcribing lyrics to the beat is an intuitive way of translating the lyricism that we hear into poetry that we can read, without sacrificing the specific relationship of words to music laid down by the MC's performance. By preserving the integrity of each line in relation to the beat, we give rap the respect it deserves as poetry. Sloppy transcriptions make it all but impossible to glean anything but the most basic insights into the verse. Careful ones, on the other hand, let us see into the inner workings of the MC's craft through the lyric artifact of its creation.

The MC's most basic challenge is this: When given a beat, what do you do? The beat is rap's beginning. Whether it's the crunching bass of a Metro Boomin beat, the hiccups and burps of a Timbaland track, knuckles knocking on a lunchroom table, a human beatbox, or simply the metronomic rhythm in an MC's head as he spits a cappella rhymes, the beat defines the limits of lyric possibility. In transcribing rap lyrics, we must have a way of representing the beat on the page.

The vast majority of rap beats are in 4/4 time, which means that each musical measure (or bar) comprises four quarter-note beats. For the rapper, one beat in a bar is akin to the literary poet's metrical foot. Just as the fifth metrical foot marks the end of a pentameter line, the fourth beat of a given bar marks the end of the MC's line. One line, in other words, is what an MC can deliver in a single musical measure-one poetic line equals one musical bar. when an MC spits sixteen bars, we should understand this as sixteen lines of rap verse.

With the spread of hip hop has come its saturation as well, even in some of the most unexpected places in culture. I'm sure John Harvard, that "godly. gentleman and lover of learning," would be nonplussed to learn of a Nasir Jones Hiphop Fellowship being run out of Harvard's own Hiphop Archive and Research Institute. Hip hop is just about everywhere.

Hip hop isn't just big business and culture, it's personal too. I often joke that hip hop and I have followed the same trajectory: born in the 80s, climbing in late 80s, reaching our peak in the '90s, and starting our slow and steady decline in the 2000s. The playful comparison calls attention to the fact that people often assume that musical genres follow the same life cycle that we humans do. Of course, history tells us otherwise. As an art form, hip hop is still in its relative infancy. We know, too, that art develops in fits and starts of sudden inspiration, that it is constantly reborn and refreshed, that its capacity for change is not subject to the frailties of human flesh. So it is with hip hop.

I believe that we are living in perhaps the most vital period that hip hop has ever seen. That's not to say that rap music has gotten better since what many consider its golden age, from the mid-1980s to the mid 1990s, only that rap's creative potential has never been more apparent. More people from more places are making more kinds of rap music than at any other time in history. There's something so durable about the structure of words rapped to a beat, something inclusive that resists any attempts to enforce some narrow orthodoxy or keep certain people out be they from another borough or coast, another gender or sexual orientation, another race or life experience. Rap is free to all those willing to assume the heavy burden of mastering its craft, of learning how to rock the mic right.

About the Creator

Brian

I am a writer. I love fiction but also I'm a watcher of the world. I like to put things in perspective not only for myself but for other people. It's the best outlet to express myself. I am a advocate for Hip Hop & Free Speech! #Philly

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.