Reflections of Traditions and Tribal Violence in the Folk Songs of Afghan Women: A Socio-Cultural Study

Exploring Hidden Voices of Resistance and Resilience in Afghan Women’s Folk Songs.

Reflections of Traditions and Tribal Violence in the Folk Songs of Afghan Women: A Socio-Cultural Study

Author: Islamuddin Feroz, Former Professor, Department of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts, Kabul University

Abstract

Folk music is one of the most important cultural tools for representing the realities of social life. In Afghanistan, folk songs, especially women’s songs, are regarded as mirrors of pain, inequality, and historical injustice. This article examines one of the prominent dimensions in this field: the reflection of outdated customs and tribal violence against women in folk songs. Examples such as walwar or toyāna (bride price), forced marriage, the phenomenon of bad dādan (giving a girl in marriage to settle disputes), badal (exchange marriage), child marriage, and promises of marriage made before the birth of children are reflected in these works. Other themes such as exile, separation from parents, poverty and deprivation, and the pain of separation from children are also highlighted in these songs. This study demonstrates how music, as a cultural text, serves not only as a tool for narrating the individual and collective suffering of women, but also functions as a historical and social document.

Keywords: folk music, women’s songs, marriage, bad dādan, badal, forced marriage, child marriage, cultural violence

Introduction

Afghanistan, as a country with vast ethnic, linguistic, and cultural diversity, possesses a rich treasury of folk songs and melodies that are not only manifestations of artistic beauty but also carry profound social, historical, and anthropological meanings. Among these works, women’s songs hold a special place. These songs provide a space for recounting women’s lived experiences in a society where their voices are often unheard within formal and patriarchal structures. Through music, women have been able to express hidden aspects of their lives—issues ranging from gender inequality and social restrictions to domestic violence and widespread economic deprivation.

From an academic perspective, the study of women’s songs is not merely a musical inquiry but rather an interdisciplinary research field that can be significant within sociology, anthropology, gender studies, and social history. These songs are not only reflections of individual emotions but also representations of power structures, tribal relations, and dominant cultural values. One of the central themes in these songs is the reflection of outdated customs and violence rooted in tribal traditions—traditions that directly affect women’s lives and restrict their individual and social freedoms. Accordingly, this article, by presenting examples of such songs, seeks to shed light on the realities of women’s lives in Afghanistan and scientifically analyze the hidden layers of folk culture.

Folk Music as a Social Mirror

Afghan folk music serves a much broader function than entertainment or pastime. In essence, it is a form of social storytelling that, through melodies, poetry, and songs, reflects everyday life, power structures, family relations, and the cultural values of society. In fact, folk music, as an oral and cultural text, transmits the history and lived experiences of people and passes them on to future generations. On one hand, this music is a mirror of joys, celebrations, and local rituals; on the other hand, it is a silent language for expressing pain, sorrow, and inequality. Women, who in many cases in Afghanistan’s traditional society lack the opportunity for active presence in the public sphere, make their voices heard through songs. For this reason, women’s songs have gained importance not only on an individual level but also on a collective level, becoming tools of cultural and social resistance.

Women’s songs are especially performed in private gatherings, wedding ceremonies, work rituals, and even during times of loneliness and exile. These songs often contain themes that are difficult or forbidden to express directly in public spaces—such as gender inequalities, domestic violence, the deprivation of the right to choose in marriage, or problems arising from poverty and social injustice. In this way, folk music becomes a space for representing issues that are ignored in official discourse or dominant narratives of power. Moreover, Afghan folk music has always maintained a deep connection with power structures and social relations. Local melodies and poems often serve as hidden critiques of the existing order and relations of domination. Through these songs, one can understand how traditions, tribal customs, and even unwritten social laws influence people’s daily lives. Women, more than others, suffer from these inequalities, and music becomes a tool for reflecting their lived experiences and their silent resistance.

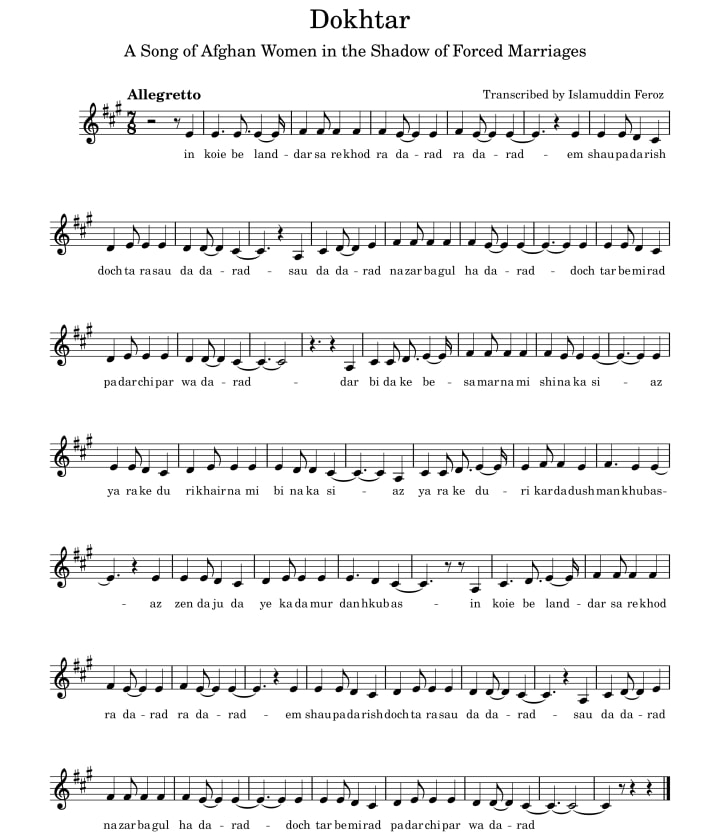

Forced Marriage and the Bargaining of Girls

There are various types of unwanted marriages of Afghan girls that have turned into sources of pain, sorrow, and torment for women, and these have been reflected as major themes in women’s songs in the form of hidden protest. It can be said that marriages at childhood ages, marriages in the form of bad dādan (giving a girl to settle disputes), marriages arranged through promises made before birth, and badal (exchange marriages) are among such unions with futures full of pain, suffering, and inequality. These songs often reflect the individual and collective experiences of women who were forced into marriage without consent and conscious choice. In such conditions, the identity and human dignity of girls are reduced to the level of a commodity, and their worth is determined mainly by the decisions of tribal elders, fathers, and other male family members. This process not only violates the dignity and fundamental rights of girls to freedom and autonomy, but also reproduces gender inequalities and patriarchal dominance within the social structure. Women’s protest songs against this situation function as an alternative discourse in which women, through poetry and music, convey their silenced voices to society. Thus, the songs are not merely artistic tools but forms of cultural resistance and indirect political action against the dominance of traditions and unjust socio-economic relations. In what follows, some of these ancient customs are analyzed, and the role of women’s songs in exposing them is examined.

Poem:

In kuh-e boland dar sar-e khod rah dare rah dare

Emshu pedarash dokhtare sauda dare

Sauda dare nazar be golha dare

Dokhtar bemirad pedar che parva dare

Dar Bidak bi samar nemishine kasi

Az yarek doori kheyr nemibine kasi

Az yarek doori karde doshman khub as

Az zende jodaei karde mordan khub as

Translation of the Poem

This tall mountain has its own path, its own path

Tonight the father has a bargain for his daughter—a bargain

He casts his eyes upon the flowers

If the daughter dies, what concern has the father?

No one sits beneath a barren willow tree

No one gains good fortune by being far from the beloved

Distance from the beloved makes even a friend an enemy

Separation from the living makes death better.

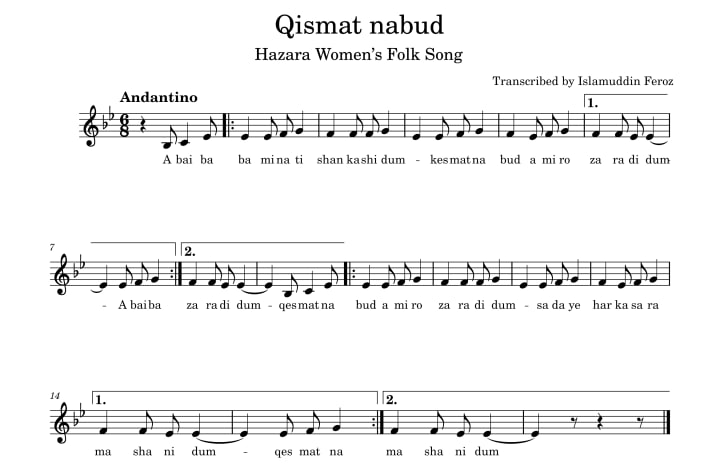

Marriage Before Puberty

Some Afghan women’s songs are devoted to the subject of early or pre-pubescent marriage and reflect the social pressures and challenges associated with this phenomenon. Early or pre-pubescent marriage, from the perspective of cultural and sociological studies, is a multidimensional issue that goes beyond an individual or family matter. The roots of this phenomenon lie in a network of interrelated factors: first, economic poverty, which drives families to use walwar or bride price as a means of financial survival; second, tribal traditions and norms, which often tie the identity and social legitimacy of a family to strict adherence to kinship rules and tribal bonds; third, social pressures related to the preservation of “honor,” which especially in patriarchal societies act as a mechanism for controlling women’s bodies and destinies; and finally, lack of awareness and access to legal rights, which limits women’s ability to resist these structures.

For this reason, these songs—through metaphorical and emotional language—represent the consequences of early marriage alongside other women’s issues; consequences such as deprivation of childhood, denial of access to education, and the unwanted imposition of the roles of wife and mother. Although expressed in a simple and folk format, these themes carry deep critical weight and can be considered micro-narratives that echo the silenced voices of women against unequal structures and gender injustices.

Poem:

Abi baba minat shan keshidam

Qesmat nabud ami roza ra didam

Qesmat nabud ami roza ra didam

Saday-e har kasara ma shenidam

Translation of the Poem:

Oh father, and Mother I bore their burdens with effort,

But it was not my fate to see these days,

It was not my fate to see these days,

I heard everyone's unhappy voices

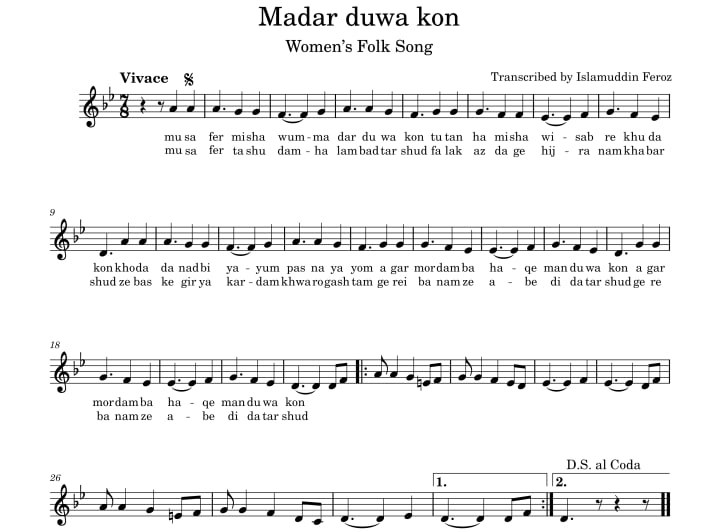

The Custom of Bad Dādan of Girls to Resolve Tribal Hostilities

The custom known as bad dādan can be considered one of the most significant manifestations of structural and gender-based violence in tribal societies, and its reflection can clearly be seen in local texts and songs. This phenomenon not only reduces the social position of women to tools for resolving hostilities and bloody conflicts, but also functions as a cultural mechanism that prioritizes the collective interests of the tribe over the individual rights of women. In such a process, girls, without personal will or choice, are forced into unwanted and compulsory marriages within the framework of traditional systems to establish peace treaties or end blood feuds. From a sociological perspective, the custom of bad demonstrates the connection between symbolic violence and patriarchal order in tribal and rural societies. Institutionalized in this way, women’s bodies and lives become domains of social exchange and bargaining, ultimately ensuring the continuity of gender inequality. On a psychological and human level, such fates reproduce suffering, enforced silence, and acceptance of oppression as “inevitable destiny,” which are reflected in folk songs through themes of mourning, longing, and hidden dissatisfaction.

Therefore, the reflection of the custom of bad dādan in Afghan women’s songs is a kind of silent and artistic protest against this unjust tradition. Women, through local songs and folklore, mirror the sorrow and anguish of being sacrificed in tribal transactions. In these songs, the bad dādan girl becomes a symbol of victimhood, deprivation of love, and loss of freedom. Music, in this context, functions as the voiceless language of women who cannot openly resist but who, through poetry and song, transmit their message of pain and resistance across generations.

Poem:

Mosafer meshawam madar dua kon

To tanha meshawi sabr-e Khoda kon

Khoda danad biayam ya nayaam

Agar mordam be haqq-e man dua kon

Mosafer ta shodam halam badtar shod

Falak az dagh-e hejranam khabar shod

Zebas ke gerya kardam khar o gashtam

Gereybanam ze aab-e dida tar shod

Translation of the Poem

I become a traveler, mother, pray for me

You will be alone — have patience and trust in God

Only God knows if I will return or not

If I die, pray for my soul

Since I became a traveler, my state grew worse

The heavens learned of the pain of my separation

So much have I wept that I became weak

My collar is soaked with the tears from my eyes

Prenatal Promises, Predetermined Futures, and the Exchange (Badal) of Girls

In some songs, Afghan women sing of fates predetermined even before their birth or of being victims of the custom of badal (exchange), where their feelings and choices are replaced by familial deals and commitments. Their voices in these verses reflect a sense of alienation in an unwanted household, a longing for freedom, and a silent protest against traditions that dictate their destinies. Prenatal promises and predetermined futures are among the other unequal social customs in Afghanistan, placing girls in particularly vulnerable positions. This tradition, usually carried out through family agreements between relatives or close friends, not only disregards the individual rights and freedom of choice of children, but also imposes unchangeable expectations and responsibilities upon them. Sociological research has shown that such predetermined decisions, by restricting personal autonomy, pave the way for psychological and emotional crises in adolescence and adulthood and may lead to emotional incompatibilities, family conflicts, and even divorce.

On the other hand, the badal of girls is another unfavorable custom that women face. In this tradition, girls, without their consent or personal will, are given between two families as part of an agreement or exchange to the sons of one another. This practice not only violates women’s independence and right of choice but also puts their future at risk. The complexity of this tradition intensifies when one party experiences violence or oppression; in such situations, the other family may retaliate in kind, and this cycle of reciprocal tension and harm increases the suffering and pressure on women. As a result, Afghan women who encounter badal often endure bitter and challenging lives, experiences marked by social restrictions, threats to physical and psychological security, and deprivation of opportunities for free choice.

Altogether, in such cases, women’s music continues to be accompanied by themes of lack of agency, imposed destiny, and emotional suffering, while at the same time representing cultural resistance and reflecting the pressures and restrictions imposed upon them by society.

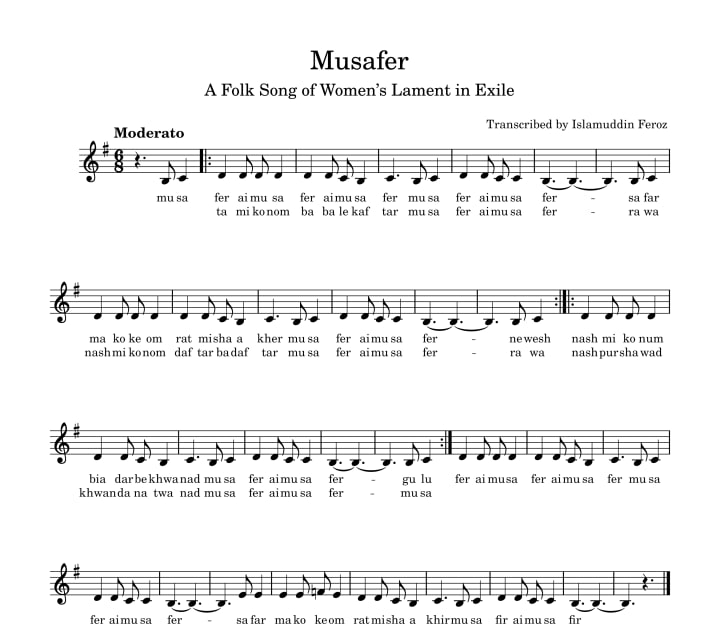

Exile, Poverty, and Separation from Family

One of the central themes of these songs is the phenomenon of alienation and rupture from kinship networks. In these verses, women bitterly express the experience of separation from their parents and familial origins—an experience often intensified by the pressures of imposed gender roles, the exhausting weight of daily tasks in the new environment, and feelings of longing. Additionally, the theme of economic deprivation occupies a prominent place in these songs. Through song, women give concrete descriptions of livelihood hardships, deprivation of economic security, and the psychological consequences arising from it. This expression is often accompanied by mourning over forced separation from children or the absence of emotional and social support from the natal family, together portraying a comprehensive picture of the multilayered roots of women’s suffering in Afghanistan’s socio-economic context. Despite all these adversities, women’s songs are not only tools of silent protest but also function as cultural and historical documents. These songs record the historical suffering of Afghan women and, from this perspective, hold great significance for social, anthropological, and gender studies research.

Poem:

Mosafer ey mosafer ey mosafer, mosafer ey mosafer

Safar mako ke omrat mesha akhar, mosafer ey mosafer

Naweshta mekonam be bal-e kaftar, mosafer ey mosafer

Rawanash mekonam daftar ba daftar, mosafer ey mosafer

Rawanash mekonam biadar bekhanad, mosafer ey mosafer

Galuyash por shawa, khandah netawanad, mosafer ey mosafer

Mosafer ey mosafer ey mosafer, mosafer ey mosafer

Safar mako ke omrat mesha akhar, mosafer ey mosafer

*

Azizan az gham o dard-e jodayi, mosafer ey mosafer

Be chashmanam nmanda roshanayi, mosafer ey mosafer

Be dard-e ghorbat o hejram gereftar, mosafer ey mosafer

Na yar o hamdami, na ashnayi, mosafer ey mosafer

Mosafer ey mosafer ey mosafer, mosafer ey mosafer

Safar mako ke omrat mesha akhar, mosafer ey mosafer

Translation of the Poem

Traveler, oh traveler, oh traveler, traveler, oh traveler,

Do not take the journey, for your life may reach its end, oh traveler, oh traveler.

I write a message upon the wings of a dove, oh traveler, oh traveler,

And send it from notebook to notebook, oh traveler, oh traveler.

I send it so my brother may read, oh traveler, oh traveler,

But his throat fills with tears, and he cannot sing, oh traveler, oh traveler.

Traveler, oh traveler, oh traveler, traveler, oh traveler,

Do not take the journey, for your life may reach its end, oh traveler, oh traveler.

*

My loved ones, from the pain and sorrow of separation, oh traveler, oh traveler,

No light remains in my eyes, oh traveler, oh traveler.

In the torment of exile and distance I am trapped, oh traveler, oh traveler,

With no friend, no companion, no familiar soul, oh traveler, oh traveler.

Traveler, oh traveler, oh traveler, traveler, oh traveler,

Do not take the journey, for your life may reach its end, oh traveler, oh traveler

Conclusion

The study of Afghan women’s songs shows that folk music functions beyond being merely an auditory art or an instrument of entertainment; in fact, it acts as a living medium for reflecting and re-creating the bitter and complex social realities. These songs emerge from women’s daily lives and, like a mirror, reflect their individual and collective experiences. Themes such as forced marriage, walwar (bride price), the custom of bad, early marriages, and even promises of marriage made before birth are reflected not as dry, objective reports but in symbolic and emotional structures that confront the listener with the depth of social pressures and suffering.

Moreover, themes such as exile, separation from family, poverty and deprivation, and estrangement from children also hold a significant place in these works. In this way, the songs not only narrate women’s individual pains but also represent the broader image of traditional society and its oppressive structures. Thus, these works can be considered a collective memory that, through music, records the unwritten history of women. On the other hand, women’s musical expression provides a space for symbolic agency and self-assertion in conditions where their right to decision-making has been taken away. Women’s singing in such contexts is not merely an expression of pain but also a hidden declaration of resistance, perseverance, and hope.

Ultimately, these songs, as an oral archive, play a fundamental role in transmitting experiences, historical memories, and cultural values, while also providing grounds for rethinking the place of women in Afghanistan’s traditional and tribal society. Furthermore, the critical and symbolic language of these works demonstrates their inherent capacity to raise awareness and to foster the emergence of gender discourses among women.

About the Creator

Prof. Islamuddin Feroz

Greetings and welcome to all friends and enthusiasts of Afghan culture, arts, and music!

I am Islamuddin Feroz, former Head and Professor of the Department of Music at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Kabul.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.