Music in the Abbasid Era: The Foundation of Islamic Music Traditions

This article examines music in the Abbasid period, exploring its key aspects, including musical development, the role of prominent musicians, and its influence on Islamic music.

Music in the Abbasid Era: The Foundation of Islamic Music Traditions

Author: Islamuddin Feroz, Former Professor, Department of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts, Kabul University

Abstract

Music during the Abbasid era, particularly in Baghdad, held a prominent place as an integral part of the cultural and artistic identity of the period. The transfer of the capital to Baghdad and the support of the caliphs, especially Harun al-Rashid and al-Ma'mun, contributed to the growth and development of both theoretical and practical music. Music schools, educational groups, and financial support for artists facilitated the emergence of prominent musicians such as Ibrahim and Ishaq al-Mawsili. Music in the court was not merely a form of luxury and entertainment; it played a role in military ceremonies, festivals, and literary and artistic gatherings. Extensive cultural exchange, translation of Greek musical texts, and the blending of traditions led to the flourishing of musical art. This period also established professional hierarchies for musicians and female vocalists, promoted high performance standards, and ensured the training of artists, with effects that continued for centuries.

Keywords: Abbasid music, Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid, music schools, Ishaq al-Mawsili, court music, military music, cultural exchange

Introduction

The Islamic Golden Age began with the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate in the mid-eighth century. The Abbasids took power in 750 CE and established Baghdad as the new capital in 762 CE. This city became the intellectual and cultural center of the Islamic world and retained this status until the weakening of the caliphate in the tenth century. Music, influenced by religious teachings and cultural interactions, became an essential part of courtly and societal life. The presence of artists, musicians, and poets from across the Islamic territories fostered cultural exchange and the emergence of new musical styles. During this period, the caliphs’ support for musicians—including awarding prizes, providing salaries, and granting property—ensured that music became not merely a leisure activity but a profession with a high social status. The first caliph to openly support music was al-Mahdi, while the most prominent patron was Harun al-Rashid, under whose court female musicians performed dances and songs using instruments such as the oud, qanun, lyre, drum, and flute. In addition to court music, military music using trumpets and drums ensured the organization and coordination of the army. Music schools and educational groups developed performance standards and trained musicians, while female vocalists played a key role in the musical hierarchy. The activities of musicians such as Ibrahim and Ishaq al-Mawsili solidified artistic traditions and creativity, ensuring the theoretical and practical expansion of Islamic music.

Flourishing and Expansion of Music during the Abbasid Caliphate

The Islamic Golden Age began in the mid-eighth century with the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate. In 750 CE, the Abbasids assumed power and moved the capital to Baghdad, which was established in 762 CE. Baghdad became the intellectual center of the Islamic states and maintained this status until the weakening of Abbasid power in the tenth century. The Abbasids were influenced by Quranic teachings and Hadith. Disciplines such as anthropology, ethnomusicology, and performance studies have long shown that music was central to religion and culture (Haris et al., 2020, p. 206). During the Abbasid era, the continuous movement of artists, scholars, religious leaders, slaves, and others facilitated extensive cultural exchange, which created new local languages for written and oral expression. This process led to the growth and expansion of literature, art, and music in the Islamic world. The period can be regarded as an era of cultural and artistic flourishing whose effects persisted for centuries. The interaction and influence of diverse cultures during this period laid the foundation for profound transformations in the cultural and artistic identity of Islamic civilization. In the ninth and tenth centuries, higher standards of performance and musicianship emerged, as prominent musicians faced increasing demand to demonstrate their technical skills. Courtly entertainments became highly lavish, and the imitation of such events by the elite promoted widespread support and significant growth of music in society (Nielson, 2021, p. 37). Music was considered part of cultural grandeur, and its importance led to the establishment of specialized schools for its study as a science. The first caliph to openly show interest in music was al-Mahdi, but the most famous patron of music in this period was Harun al-Rashid (786–809 CE). Harun al-Rashid’s name is closely associated with the famous tales of One Thousand and One Nights, and his reign is recognized as a golden age of art and music (Hatter, 2015, p. 2679).

In Harun’s palace, female slaves performed only dances, singing, and playing instruments such as the drum, lyre, oud, flute, qanun, and santur. Zaidan writes that in the court of al-Amin there were 100 female singers and musicians; in each session, ten women performed with their instruments, played a specific melody, and then left, after which the next group performed a different melody. This rotation continued until all one hundred performed ten different melodies. Zaidan also adds that as the wealth of the Abbasid caliphs increased, their lavish lifestyle intensified, and musicians, doctors, and entertainers joined the court to satisfy the demands of luxury and pleasure. Sources of wealth in the cities flourished, and urban residents, under the protection of the caliphs and state officials, indulged in leisure and entertainment, selling various goods, while receiving rewards, robes, and gifts. Musicians, singers, and poets in the palaces of elites entertained and delighted their audiences with excellent performances, music, and poetry (Zaidan, 1372, pp. 336–337, 342–377).

The Abbasids in Baghdad supported musicians who came to the city from across the Islamic territories, turning music into a tool to showcase the grandeur of the caliphate. These patronages facilitated the expansion of music and the blending of diverse traditions, bringing musical art to a peak of creativity and flourishing during this period (Lucas, 2019, p. 35). During the caliphate of al-Ma'mun, the Bayt al-Hikmah project, as a center for the translation and dissemination of various sciences, played a crucial role in transmitting Greek knowledge to the Islamic world. In this context, Muslims translated several musical treatises by prominent Greek authors such as Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Nicomachus. Muslim scholars refined these texts, which encompassed both theoretical and practical knowledge of music, and aligned them with Islamic principles and values to present them in a form suitable for the contemporary Islamic society.

Consequently, music held a prominent position in the culture and arts of that era, particularly due to the efforts of figures like Ishaq al-Mawsili (767–850 CE), whose activities led to unprecedented growth and prosperity in musical art. Ishaq al-Mawsili, through the creation of enduring works and the revival of Arab musical traditions, played a fundamental role in consolidating and expanding this art in the Abbasid court, earning recognition as one of the most influential musicians in history (Saoud, 2004, p. 3). The Abbasid caliphs, by allocating substantial budgets to support artists, created favorable conditions for the growth and flourishing of music. This support included generous stipends, awarding valuable prizes, and even granting land or property to distinguished musicians. In this way, musicians not only gained widespread fame among both elites and the general public but also accumulated considerable wealth and attained a special social status (Arbor, 2018, p. 28).

Musicianship standards and the distinction between elite music and popular genres significantly developed in the eighth and ninth centuries with the establishment of music schools. These schools did not necessarily exist as physical buildings but often referred to educational groups associated with prominent teachers. Most musicians learned their art through apprenticeship under a master. In this system, musicians, whether free or enslaved, were recognized as members of a school or branch belonging to their teacher. Initially, music schools were primarily established to train female slave singers. Ibrahim al-Mawsili (742–804 CE), a prominent musician, father of Ishaq al-Mawsili, and close friend of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, was among the first to establish a music school and selected female slaves for training. Nielson, citing al-Isfahani, notes that Ibrahim al-Mawsili founded his school partly to standardize music education, while simultaneously gaining substantial financial profit from selling the women under training. Furthermore, the establishment of music schools played a key role in reducing social restrictions on men pursuing careers as musicians, allowing them to study music professionally and benefit from financial support (Nielson, 2021, pp. 43–44).

During the early period of the Abbasid Caliphate, female singers typically performed behind a curtain, but in later periods, the Abbasid caliphs brought them onto more public stages, exposing their performances fully to the audience. In the ninth and tenth centuries, a complex and multi-layered hierarchy emerged in the musical sphere, where musical skill, social status, and political influence played a central role in determining individuals’ positions. Part of this hierarchy was led by prominent female singers. At the top of this social structure were groups such as the qiyan, court companions (nadim), enslaved musician girls, selected free and noble women, mukhannathun (eunuchs), and male musicians. Musical-poetic gatherings, known as majlis (plural: majalis), were organized by rulers, courtiers, and members of the wealthy classes and included poetry recitation, music, wine drinking, and occasionally romantic activities. These gatherings had a ceremonial structure but could also be spontaneous or pre-planned, sometimes lasting for several days (Ibid, 2021, pp. 53–69, 170).

Islamic musicians, in addition to inventing new musical instruments and developing novel styles and techniques, authored valuable treatises on music. The caliphs made efforts to promote and refine music by all available means. They ensured that vocalists were educated and literate, capable of correctly reciting poetry. Caliphs often gathered composers for debates and research, rewarding the best with prizes and stipends, and granting slaves, concubines, and camels (Zaidan, 1372, p. 622).

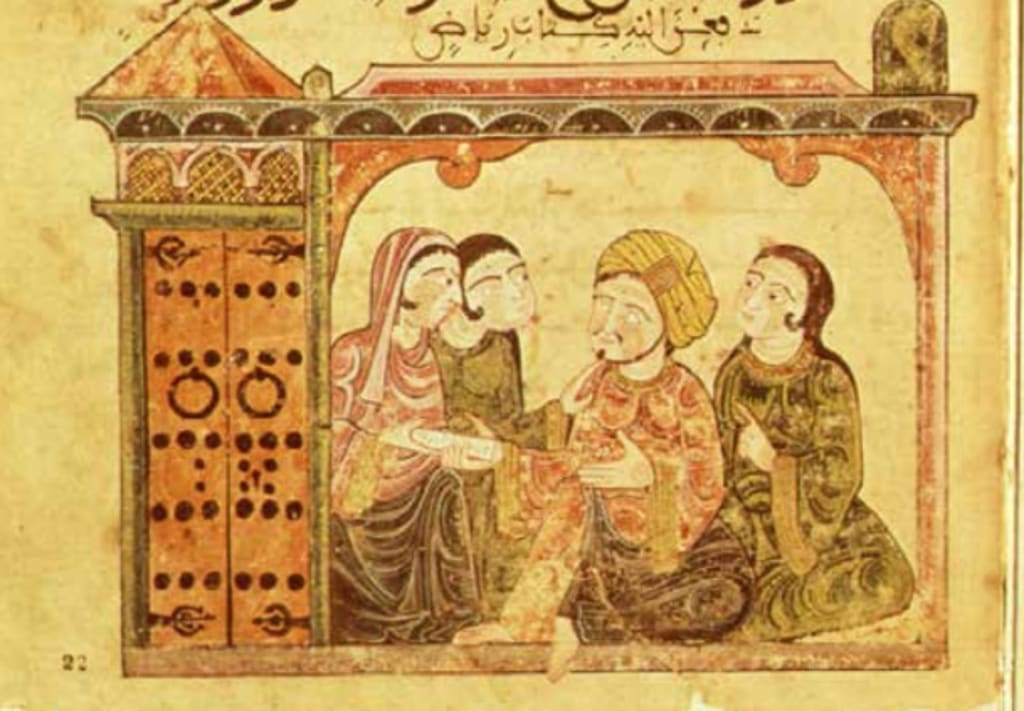

During the Abbasid period, music also played an important role on the battlefield. Instruments such as trumpets and large drums were used to coordinate and motivate troops, as well as to transmit messages and commands during combat. Military music reflected the advanced organizational structure and discipline of the Abbasid army. The sound of trumpets and drumbeats heightened the excitement of the battlefield and prepared warriors for combat. This tradition formed an integral part of Abbasid military culture and is depicted in both artworks and historical texts.

The miniature referenced here belongs to the Maqamat al-Hariri manuscript, created in Baghdad in 1237 CE. This manuscript is one of the most famous illustrated versions of Maqamat al-Hariri, a work written by the Arab author Qasim ibn Ali al-Hariri in the twelfth century, containing stories in rhymed and eloquent prose. The manuscript includes miniatures inspired by the artistic style prevalent during the Abbasid period in Baghdad. At that time, Baghdad was one of the major scientific and cultural centers of the Islamic world, and the art of miniature painting reached its peak there. This particular miniature depicts the use of trumpets and large drums in Abbasid-era Islamic battles and, alongside other features of the manuscript, plays a key role in documenting the military culture and traditions of the period. After the glorious era of Caliph al-Ma'mun, subsequent Abbasid rulers weakened and became entangled in internal conflicts and lavish lifestyles. From the ninth century onward, Abbasid authority declined, leading to the emergence of several semi-independent states in Khorasan. As a result, independent Muslim dynasties such as the Tahirids (821–873 CE), Saffarids (867–903 CE), Samanids (875–1005 CE), Ghaznavids (977–1186 CE), Seljuks (1037–1192 CE), Ghurids (1149–1212 CE), and Khwarazmians (1077–1231 CE) rose to power across the broader region of Khorasan (Israt & Islam, 2013, p. 34).

Conclusion

The study of music during the Abbasid era demonstrates that this art extended beyond mere entertainment or courtly activity and played a significant role in shaping the cultural and social identity of the period. Material and moral support from the caliphs, especially Harun al-Rashid and al-Ma'mun, enabled prominent musicians to research, teach, and create new works, giving rise to organized musical traditions and educational institutions. The Abbasid experience shows that music could serve as a means of cultural exchange, the promotion of knowledge, and even the consolidation of political authority, as it was not only a form of entertainment in the court but also a symbol of caliphal grandeur and a benchmark for standardizing artistic culture.

Moreover, the presence of female singers and qiyan in courtly gatherings and their significant role in training and performance reflect the flexibility of the social and artistic structure of this period. Additionally, the integration of diverse musical traditions from across the Islamic world and the reinterpretation of Greek musical texts indicate the Abbasid society’s high capacity for cultural coexistence and innovation. The history of Abbasid music demonstrates that its growth relied on three key elements: political and economic support, an organized educational structure, and extensive cultural interaction. Ultimately, music in the Abbasid era laid a solid foundation for the development of Islamic music in subsequent centuries. The caliphs’ patronage, the establishment of music schools, and the work of prominent musicians ensured that theoretical and practical musical traditions were standardized and consolidated. This period demonstrated that a combination of structured education, artistic innovation, and caliphal support could foster a sustainable musical culture. Many of the modes, styles, and performance techniques developed in the late Abbasid period were used and further evolved in later Islamic eras, and the musical achievements of the Abbasids remain a model for Islamic musical art.

References

Arbor, Ann. (2018). The modal system of Arabian and Persian music, 1250 - 1500: An interpretation of contemporary texts. Owen Wright. Eisenhower: ProQuest LLC.

Hattar, Renee Hanna. (2015). Music and Interfaith Dialogue: Christian Influences in Arabic Islamic Music. International Center for the Study of Christian Orient, Granada, Spain. Middle East Journal of Scientific Research 23 (11): 2676-2682, 2015 ISSN 1990-9233 © IDOSI Publications.

Haris, Saidah. Ganesan Shanmugavelu. Hanizah, Abdul Bahar. (2020). musicology in Islam Preliminary study. EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR) - Peer Reviewed Journal Volume: 6. Pp 206-213.

Hamoud Maidi, Anis. (2021). The Journey of Music and Singing from Babylon to Baghdad: An Introduction to the Development of Iraqi Music. Peer-Reviewed Scientific Journal, First Issue Published in April 2008, Issue No. 54, Summer 2021. Pp 164-182.

Israt Ara, Aniba and Islam, Arshad . (2013). Chinggis Khan And His Conquest Of Khorasan: Causes And Consequences. International Islamic University Malaysia.

Lucas, Ann E. (2019). Title: Music of a thousand years: a new history of Persian musical traditions. California: publisher University of California Pres.

Nielson, Lisa. (2021). Music and Musicians in the Medieval Islamicate World A Social History. London: I.B. TAURIS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Saoud, Rabah. (2004). The Arab Contribution to Music of the Western World. Manchester: Lamaan Ball MPhys.

Towers, Sha. (1997). The trombone as signifier in sacred Germanic works of the 17th and 18th centuries. Master Degree. Advisor: Harry Elzinga. Texas: Baylor University.

Zaidan, Jurji. (1993). The History of Islamic Civilization. Translated by Ali Javaherkalam, Tehran: Amir Kabir.

About the Creator

Prof. Islamuddin Feroz

Greetings and welcome to all friends and enthusiasts of Afghan culture, arts, and music!

I am Islamuddin Feroz, former Head and Professor of the Department of Music at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Kabul.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.