From Samarkand to Herat: Rudaki and the Shared Musical Identity of Afghanistan and Central Asia

"Exploring how Rudaki’s poetry resonates across borders, shaping a shared cultural and musical heritage. A journey through the intertwined artistic identity of Afghanistan and Central Asia."

From Samarkand to Herat: Rudaki and the Shared Musical Identity of Afghanistan and Central Asia

Author: Eslâmuddin Firooz, Former Professor, Department of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts, Kabul University

Abstract

Rudaki, the great poet of the 10th century CE (4th century AH), is not only regarded as the founder of Persian Dari poetry but also as one of the most significant figures in the cultural and artistic history of Greater Khorasan. His works and personality created a bridge between the literary and musical traditions of Central Asia and Afghanistan. Through an interdisciplinary lens, this article explores Rudaki’s role in shaping and sustaining the shared musical elements spanning from Bukhara to Herat. By analyzing historical sources, literary descriptions, and the role of music in the Samanid court, it becomes evident that Rudaki was not only a poet but also a skillful musician and minstrel who profoundly influenced the evolution of music within the cultural sphere of Khorasan. The article also reveals the cultural continuities between modern Afghanistan and Rudaki’s legacy, as well as the Khorasani musical heritage.

Keywords: Rudaki, Khorasani music, Afghanistan, Central Asia, Samanid culture, musical identity

Introduction

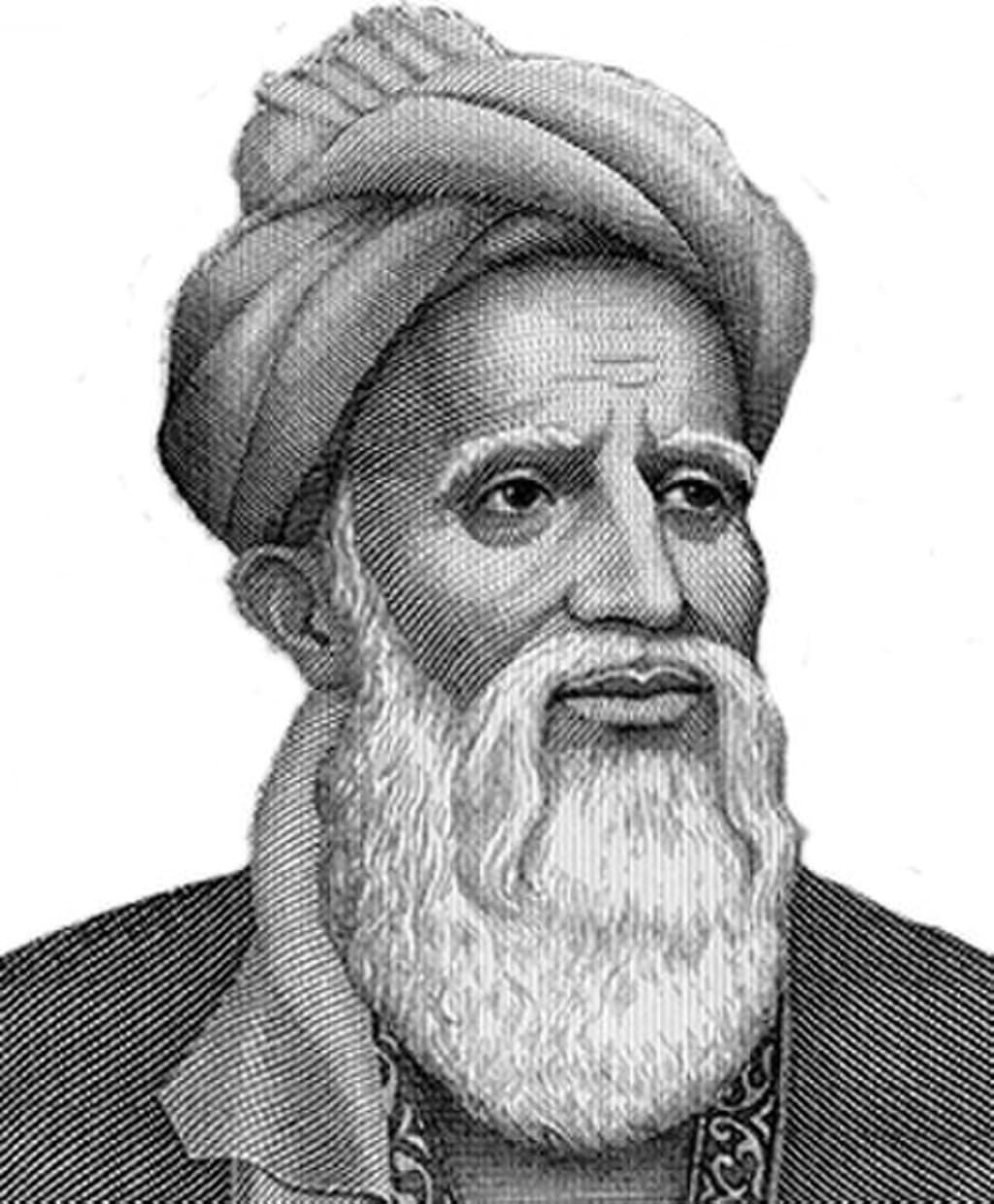

Throughout the vast history of Greater Khorasan’s civilization, few figures have played as enduring a role in linking art and thought as Abu Abdullah Ja‘far ibn Muhammad Rudaki (ca. 244–329 AH / 858–940 CE). Born in the village of Panj near Samarkand, he soon transcended the geographical limits of his birthplace and found his way to the Samanid court in Bukhara. Rudaki was among the first poets to elevate the Persian Dari language to new heights, and his poetry—alongside melody and music—created a new medium for expressing emotions and ideas.

Rudaki lived at a time when Bukhara, Samarkand, Balkh, and Herat were interconnected through networks of cultural, commercial, and artistic exchange. Poetry and music were the two main pillars of this connection. Music was not merely a means of courtly entertainment but a shared language of the people of Khorasan. Examining Rudaki’s place within this context provides an opportunity to trace the common roots of Afghan and Central Asian music—roots that continue to thrive today through Khorasani melodies and ancient musical instruments.

Historical and Cultural Background of Rudaki’s Era

During the 9th and 10th centuries CE, the musical culture of Khorasan and Transoxiana—whose origins stretched back to ancient times—continued to develop and flourish. The peoples of these regions possessed long-standing traditions of virtuoso performance and advanced musical theory. In this period, distinctive patterns emerged in various artistic and musical styles. Professional classical music, preserved through oral traditions and often performed with sung poetry, continued to be produced; later, these compositions were compiled into the Twelve Maqams (Twelve Modes), which were subsequently reinterpreted as the Six Maqams (Six Modes). Poetry and song were not merely intertwined—they were regarded as branches of a single art form. Folk art played a decisive role in the growth and expansion of professional poetry and music (Negmatov, 1998, p. 98).

The primary format of works by court poets and musicians was the qasida (ode) in praise of kings. The opening section of these poems (nasīb) was often accompanied by instrumental music. These preludes were sometimes performed independently during evening gatherings. Out of the nasīb emerged the ghazal—a musical and poetic art form performed independently by singers, instrumentalists, or minstrels. Some songs also expressed social and political commentary. Satirical songs mocked the greed and corruption of kings and courtiers, as well as the hypocrisy and fanaticism of clerics. Hidden beneath layers of irony and humor, these works quickly gained popularity among the people (Abdumutalibovich, 2022, p. 527).

Music had become an inseparable part of all aspects of social life, playing a vital role in weddings and celebrations, festivals and battles, commemorations and official ceremonies, as well as in religious rites and mourning rituals. Some of the musical modes of that time included Khosravani, Sarud (Ruh, Khafif), and Tarana, among others. Numerous melodies were also in use, such as Khosravani, ‘Ushshaq, Rast, Badāha, ‘Iraq, Zirafkand, Busalik, Sipahan, Nawā, Basta, Chawash, etc. (Negmatov, 1998, p. 99).

From the beginning of the Islamic era, Khorasanian music was regarded as something distinct and unique. Musical instruments from this region were sent to the Umayyad Caliph in Damascus, and female singers from Khorasan performed at the Abbasid court in Baghdad. Bukhara was renowned for its distinctive musical style, including the “marvelous songs” about the legendary ruler Siyavash and traditional laments that evolved into refined art songs. Solo instrumental pieces known as Rāvishan—which, according to accounts, “no human voice could imitate”—were identified by al-Farabi (d. 950 CE), the great theorist of Islamic music, as characteristic of the Khorasanian style (Neubauer, 2000, p. 600).

In this period, special attention was paid to the method, rhythm, and style of musical performance—an approach that led to the refinement of Khorasanian and Transoxianian music and expanded its influence throughout the Islamic world. Musicians of these regions, drawing on local traditions and integrating them with musical elements from neighboring lands, developed new and sophisticated structures of melody and rhythm. These innovations were warmly welcomed at the Samanid courts and spread through royal courts and cultural centers to Baghdad, Ray, Bukhara, and even lands beyond the frontiers of Transoxiana and Khorasan. Consequently, Khorasanian and Transoxianian music became models for courtly music across the Islamic world, and many of its terms, instruments, and modes gained popularity among various peoples and dynasties.

Rudaki and His Musical Status

In ancient sources, Rudaki is referred to as the “Master of Minstrels” and the “Composer of Bukhara.” It is said that he was skilled in playing the ‘ud (lute) and chang (harp), and that many of his poems were composed to be sung with melody. He was likely born in 858 CE and died in 329 AH (940–941 CE). Muhammad Awfi (d. 1237 CE), author of the poetic anthology Lubab al-Albab, provides the most detailed biographical account of Rudaki. He reports that Rudaki was born in the village of Rudak and was blind from birth, yet possessed extraordinary talent. By the age of eight, he had memorized the Qur’an and mastered its recitation. From childhood, Rudaki began composing poetry and, due to his remarkable voice, became interested in music, learning to play the barbat (lute) under his teacher Abu’l-Abbāqā Bakhtiyar. His fame spread far and wide during his lifetime, reaching even the court of Amir Nasr ibn Ahmad al-Samani, who invited him to his court.

Despite reports of Rudaki’s congenital blindness, historical evidence suggests that he may have been either blind or visually impaired; however, his literary and musical talents were unparalleled. Detailed studies indicate that Rudaki began composing poetry and playing music in his youth, before moving to Samarkand, where he later pursued religious and secular studies. The surviving works of Rudaki, in addition to reflecting his literary prowess, demonstrate his vast knowledge of theology, history, Eastern and ancient Greek philosophy (through Arabic translations), cosmology, and the natural sciences. He was also fluent in Middle Persian (Pahlavi), a language revered at the time as the tongue of pre-Islamic Aryana’s cultural heritage. In his youth, whether in his native village or in Samarkand, Rudaki was already recognized as a distinguished poet, singer, and musician (Khadi-zade, 1985, p. 15).

Khorasani Music and Shared Cultural Identity

Afghanistan’s music is among the oldest artistic traditions in Central Asia, deeply rooted in the history, culture, and indigenous traditions of the region. During the Samanid era—one of the most illustrious periods of this civilization and the point of connection between the musical cultures of Afghanistan and Central Asia—music held a distinguished position both at court and among the people. Cities such as Balkh, Bukhara, and Herat were among the foremost cultural and artistic centers of that era, where many renowned musicians were active (Ismailov, 2018, p. 46). From that time onward, Afghan folk songs and melodies became inseparably linked with Persian poetry and classical literature. Instruments such as the rubab, tanbur, and dutar are precious legacies of that age and remain prominent in Afghan music today. The influence of Samanid music on the musical styles of various regions of Afghanistan is still perceptible; though transformed over time, it has retained its authenticity and cultural identity.

The Persian poetry of Rudaki, the great poet of Samarkand, represents a vivid symbol of the cultural continuity among the lands of Greater Khorasan. His poems and songs not only played a foundational role in linking poetry and music but also paved the way for the formation of Persian-speaking musical traditions across the region. Rudaki’s legacy extends beyond modern Tajikistan—it encompasses Afghanistan and the entire expanse of Central Asia. The shared language, music, and culture of these peoples are reflected in Rudaki’s works. He stands as a symbol of cultural unity among the nations and ethnic groups of this vast civilizational sphere—a unity that remains alive and enduring in the collective memory of the region’s people.

The Interrelation of Poetry and Music in Rudaki’s Works

In Khorasani culture, poetry and music have always interacted closely. Rudaki’s poetry was composed with a natural rhythm and melody that made it suitable for musical performance. In many cases, the metrical structures of his verses were based on musical rhythms. For example, the poetic meters ramal and hazaj, frequently used in his poems, are the same rhythmic patterns later heard in the maqam traditions of Afghanistan and Central Asia. This indicates that Rudaki not only composed poetry but did so with a distinctly musical sensibility.

Moreover, the themes of Rudaki’s poetry—nature, love, wine, and the enjoyment of life—are motifs that later echoed throughout Khorasani music. In this cultural context, music was not merely ritualistic; it was an expression of the Khorasani spirit’s delicacy and aesthetic sensibility (Asparham, 2008, p. 108).

Rudaki and Music at the Samanid Court

The court of Nasr ibn Ahmad al-Samani can be regarded as one of the first “official centers of art” in the Persian world. There, musicians, poets, and scholars from across the eastern lands of the Islamic Caliphate gathered. In such an environment, Rudaki was not only the court poet but also its official musician. Historical sources note that he used the chang (harp) and ‘ud (lute) while reciting his poetry and was sometimes accompanied by a group of instrumentalists (Farmer, 1992, p. 139).

This practice later evolved into the traditions of maqamkhani (performing maqams) and group dutar performance in Afghanistan and Tajikistan. In fact, Rudaki can be seen as the founder of the “poet-musician” tradition in Persian culture—a lineage continued by figures such as Baba Taher, Amir Khusrow Dehlavi, and later by Nasir Khusrow and the poet-singers of Herat.

The Continuation of Rudaki’s Legacy in Afghanistan

Although Rudaki’s birthplace lies within the modern borders of Tajikistan, his cultural influence in Afghanistan extends far beyond geographical boundaries. In later centuries—especially during the Timurid period in Herat—Rudaki’s poetry and music continued to serve as models. In Herat, musicians such as Abdulrahman Jami and Qasem Heravi referred to the connection between poetry and music in their works, echoing Rudaki’s tradition (Abdumutalibovich, 2022, p. 533).

In northern and western Afghanistan, dutar melodies and local songs still bear traces of the ancient Bukharan modes. Culturally, Afghanistan is the true inheritor of a significant part of the Khorasani heritage in which Rudaki’s roots lie. The maqami music of Badakhshan, Balkh, Takhar, and Herat—despite dialectal variations—all draw inspiration from the same spirit and musical structure of Greater Khorasan.

Rudaki and the Shared Cultural Identity

As one of the most distinguished cultural and artistic figures of Greater Khorasan, Rudaki represents the “shared cultural identity” among Persian-speaking communities of Central Asia and Afghanistan. He lived in an era before modern political borders existed, when the concept of “Greater Khorasan” functioned as a unified cultural and linguistic realm. Rudaki composed his poetry in Persian Dari—the language that later took deep root in Afghanistan and was used throughout Khorasan.

His melodies and verses, performed in Bukhara and Samarkand—regions now part of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan—carried the same musical spirit heard in Herat, Balkh, and other Afghan cities. Among historical accounts, the famous story told by Nizami Aruzi of Samarkand in his Chahar Maqala (Four Discourses) offers a striking example of this cultural continuity. He recounts that Amir Nasr ibn Ahmad al-Samani, who resided in Bukhara during the winters and in the cities of Khorasan during the summers, once spent four consecutive years in Herat and became enchanted by its climate. When his commanders grew concerned over the people of Bukhara longing for their ruler’s return, they went to Rudaki and asked him to persuade the Amir to go back. Understanding the Amir’s gentle temperament, Rudaki took up his chang and performed his famous qasida with a tender melody before him:

Būy-i Jūy-i Mūliyān āyad hamī

Yād-i yār-i mehrabān āyad hamī

(“The scent of the stream of Muliyan comes to me,

And the memory of my kind beloved comes to me.”)

Upon hearing this melody, the Amir was deeply moved and immediately ordered the army to return to Bukhara (Khadi-zade, 1985, p. 19). This account is more than a historical anecdote; it reflects the emotional, cultural, and musical bond between two key centers of Khorasan—Bukhara and Herat. The melody of Rudaki, which echoed through the soil of Herat and touched the heart of the Bukharan ruler, symbolizes the same cultural and historical unity that has long connected the peoples of these lands. From this perspective, Rudaki’s poetry and music transcend political boundaries, existing instead within the shared emotional, linguistic, and cultural domain of Khorasan—serving as a living symbol of Afghanistan’s historical connection to the nations of Central Asia.

Rudaki’s Influence in the Contemporary Music of the Region

In the 20th and 21st centuries, with the revival of traditional music in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, Rudaki’s name once again emerged in musical compositions. In Tajikistan, ensembles such as Shadkam and the Maqamkhani of Bukhara have performed Rudaki’s poetry within the maqam musical framework. In Afghanistan, maqam performers from Pamir, Sar-e Pul, Badghis, Ghor, Herat, and Faryab, as well as artists like Ustad Sarahang, Ahmad Zahir, Mullah Taj Muhammad Sarpuli, and Dawood Pazhman, have drawn inspiration from Rudaki’s verses in some of their works.

The presence of Rudaki’s name and poetry in contemporary music attests to a cultural continuity that spans over a millennium. Today, scholars of Afghan and Central Asian music believe that the roots of many maqams—including Rast, Nawa-yi Khorasani, and Husseini—are linked to the traditions established by Rudaki and the musicians of the Samanid court.

Conclusion

Rudaki was not only the first great poet of the Persian language but also one of the most distinguished symbols of cultural, linguistic, and musical unity across the vast region of Greater Khorasan. In an era when no political borders divided the cultural lands, poetry and music served as the common language of the people of these territories, and Rudaki can be regarded as the point where these two arts converged. Through his poetic fusion of word and melody, he created a world of emotion and meaning that extended far beyond the Samanid court, encompassing the entire sphere of Iranian–Khorasani civilization. An analysis of Rudaki’s position in the history of culture and music shows that, in his time, music was not merely a courtly art but a medium for cultural cohesion, the transmission of ideas, and the creation of social unity. The melodies born in Bukhara resonated through the mountains of Badakhshan, the streets of Herat, and the plains of Balkh; this very cultural resonance sowed the seeds of a bond that has endured to this day in the form of maqam music and Persian poetry in Afghanistan and Central Asia. His poems—such as the immortal qasida “Būy-i Jūy-i Mūliyān” (“The Scent of the Stream of Muliyan”)—have found a permanent place in the collective memory of the people of these lands and have been repeatedly performed by Afghan and Tajik artists.

The continued life of his poetry through music shows that Rudaki’s legacy is still alive and serves as a symbol of the historical and cultural connection between Afghanistan and the countries of Central Asia. From both historical and artistic perspectives, Rudaki can be seen as the founder of a form of Khorasani poetry and music that transcends borders—a heritage that, from Bukhara to Herat and from Samarkand to Kabul, has endured in the cultural memory of the people. Among the musical instruments of this tradition, the chahartar of Herat recalls that ancient union of melody and word that Rudaki embodied in the 10th century in a form both artistic and soul-enriching. Thus, it may be said that Rudaki was not only the founder of Persian Dari poetry but also a bridge between the eastern and western parts of Khorasan, between tradition and innovation, and between history and the present. His voice—resounding from Rudaki’s chang (harp) to Herat’s chahartar—echoes the shared cultural spirit of the peoples of this region, a spirit born from the depths of history and still alive in the songs and melodies of these lands.

References

Asparham, Davoud. (2008). Music and the Recitation of Rudaki’s Poems. Journal of Persian Language and Literature, No. 38, pp. 107–127.

Abdumutalibovich, Marufjon Ashurov. (2022) Musical Life in The Samanid Period in The IX-X Centuries Anduzbek Music in the XI-XV Centuries. Andijan State University named after Zahiriddin Muhammad Babur, Faculty of Art History, Associate Professor of Music Education. Volume: 22 . ISSN: 2545-0573. Pp 527- 537.

Farmer, Henry George. (1992). A History of Arabian Music. London: Luzac & co.

Ismailov, Israel. (2018). Born in Afshan. Tashkent: Hilol Media Publishing House.

Khadi-zade, R. (1985). Rudaki and poets of his time. Leningrad: © Publishing House Soviet Writer.

Neubauer, E. (2000). Music in the Islamic Environment. History of Civilizations of Central Isia Volume IV. Paris: United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO.

Negmatov N. N. (1998). The Samanid State. History of Civilizations of Central Asia The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Volume IV. Part One The historical, social and economic setting Editors: M. S. Asimov and C. E. Bosworth Multiple History Series UNESCO Publishing.

About the Creator

Prof. Islamuddin Feroz

Greetings and welcome to all friends and enthusiasts of Afghan culture, arts, and music!

I am Islamuddin Feroz, former Head and Professor of the Department of Music at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Kabul.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.