"Come On The Amazing Journey"

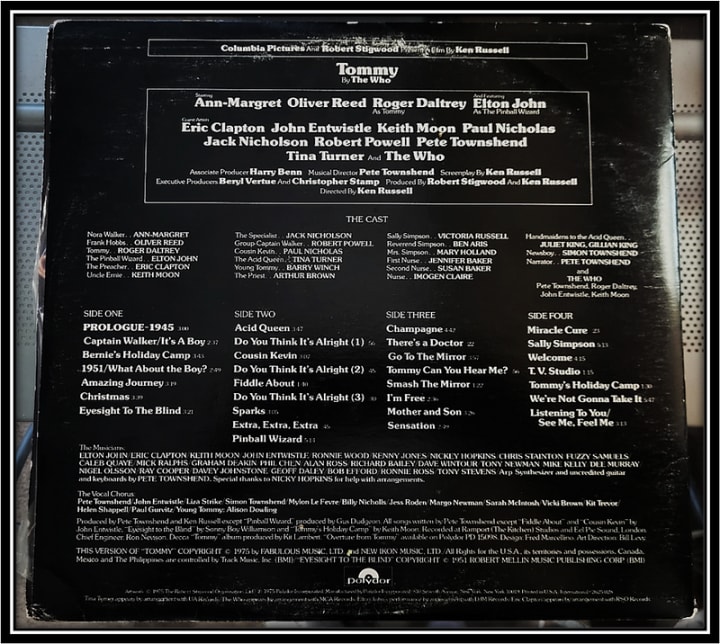

Reviewing Tommy (1975) The Movie & The Soundtrack

“I saw the film Tommy on cable television, and despite Jack Nicholson’s heinous rendition of “Go to The Mirror”, I was deeply moved by the music and the story.” — Jack Black honoring Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend at the 2008 Kennedy Center Honors.

A few years ago, I went to a downtown Vegas record store to see a friend sing a Jazz set in a small performing space in the store’s backroom. On my way out of the store after the gig, I engaged in my longtime habit (or obsession) of collecting vinyl records. One of the records I ended up taking home with me that night was the double album soundtrack for 1975’s Tommy, the film version of The Who’s groundbreaking 1969 rock opera. I had already seen the movie Tommy endlessly in my formative youth, first on cable TV, and then as part of a music appreciation class during my sophomore year in high school in the mid-2000s.

Here’s where things got interesting. There was no price tag on the Tommy soundtrack, and the record store clerk decided, for whatever reason, to give me the album for free. If I remember, he also said that since it was not technically the actual album Tommy, it wasn’t as valuable and worth spending time searching for the price value.

That does seem to reflect the view of some toward director Ken Russell’s movie version of Tommy, which has its fans and detractors. The recent Broadway revival of Tommy, overseen by Townshend himself more than 30 years after the show’s first Broadway run, made it a good time to reconsider the film, which stands as one of my favorite movie musicals.

I have always been more drawn to musicals with a dark edge, specifically those that followed the wake of 1972’s Cabaret, which deconstructed the musical and the idea of the musical as escapism. I could write endlessly about the debt I owe to 1981’s Pennies from Heaven for introducing me to the mind of Dennis Potter, and I have a deep love for 1986’s Little Shop of Horrors (no matter which endings of LSOH I see.) Tommy certainly belongs in that offbeat company, a concept musical that takes sharp hits on religion, cult stature, celebrity, infidelity, both sexual and physical abuse, and the crazy things we will do in search of meaning and answers.

Who would imagine a film that famously has its leading lady rolling around in chocolate and baked beans could contain all that?

The leading lady in question is Ann-Margret, who delivers an Oscar-nominated powerhouse of a performance as Nora Walker, a riveter in an England trapped in World War II. While the original album was set in World War I, Daltrey, Townshend, and the filmmakers decided to move the action up one World War, one of many crucial changes in the plot that mark this Tommy as slightly separate from its source material.

When Nora gets the tragic news that her husband (Robert Powell), a captain flying in combat, is missing and presumed dead, she is understandably shattered. Hope soon springs anew for Nora when her son Tommy is born just in time to enter a postwar world. Six years later, Nora and Tommy (Barry Winch, at age 6) take a vacation at a getaway camp where they catch the eye of camp counselor Frank (Oliver Reed.) Nora is quickly smitten, and Tommy also grows to like the surrogate uncle who provides the male figure that Tommy lost with his dead father.

Just as 1951 is shaping up to promise only good things, the light and loving mood turns dark. Without giving away much, Nora and Frank are soon involved in a surprising and tragic twist that, unfortunately, Tommy gets swept up in.

In the dark shadows and the sweaty heat of passion and terror, Nora and Frank shout over and over at poor Tommy that he didn’t “hear” or “see” the dark deed that had been done, turning the young boy into a blind, deaf, and dumb soul, trapped within himself.

Amazingly, Tommy’s plot expands from the personal trials to the universal ramifications. As Tommy grows into finally being played by Roger Daltrey himself, the trials and tests Tommy goes through take the audience into levels of shock and despair. Daltrey’s frozen expression still carries enough emotion, especially in the singer’s eyes, that we can sense the pain, the helplessness, and the mercy we viewers wish on him as he is placed through a parade of heartless figures who treat him with reactions that range from indifference to pity to, in the case of his joyfully bullying Cousin Kevin (a scene-stealing Paul Nicolas), sadistic cruelty. Steve Martin’s sadistic dentist from Little Shop of Horrors almost gets a run for his money with Nicolas’ happy torture of Tommy.

Without question, the most queasy and uncomfortable section of Tommy involves Keith Moon’s savage, frightening, and darkly funny Uncle Ernie. Moon is undoubtedly great, playing to the back of the room and going beyond even some of the star cameos. However, Uncle Ernie engages in behavior that cancels out the clownish nature of a man claiming to be "fiddling about".

I imagine audiences today would feel uneasy with Ernie’s actions and lack of ramifications, especially with how he figures into the plot later.

The parade of guest stars reads like a who’s who of the defining figures of the 1960s and 1970s. Eric Clapton is a Marlyn Monroe-worshipping priest who promises a cure for the lame like Tommy. Jack Nicholson pops in for a mini Carnal Knowledge reunion with Ann-Margret, playing a doctor who helps crack the secret of Tommy’s spirit still existing within him. The Doctor also briefly awakens something in the emotionally broken Nora, whose residual guilt over her part in Tommy’s plight has driven her to alcohol and the resulting hallucinations.

(Knowing Jack Black’s dislike of Nicholson’s turn, I wonder what Black would have thought of the original actor set to play the doctor, Christopher Lee, who dropped out of Tommy at the last minute.)

The two most memorable guest star turns came from Elton John as the champion Pinball Wizard and Tina Turner as the drug-addled Acid Queen. In both cases, they almost claim the definitive versions of songs once sung by Roger and Pete. Both Elton and Tina were at the top of their musical powers by 1975 and they more than deliver with their showy turns. Tina Turner hits it out of the park, especially, with a performance that contains humor, darkness, and a sense of power and control even as she is deep in the throws of drugs.

Reportedly, Tommy ended up being a crucial project for Turner, who not only became friends with Ann-Margret but landed one of her biggest projects that didn’t involve her partner/abusive husband Ike. Turner would even title her next (solo) album, released a year after the movie, Acid Queen. Shortly after, Tina would finally leave Ike and begin a hard but successful climb back to the top as a superstar in her own right.

As for Elton John, Tommy was arguably a capper to his remarkable five-year run of #1 albums, sold-out arena tours, and a persona as large as his legendary on-stage costumes. Like Turner’s Acid Queen, John takes control with fiery vocal energy that matches his pinball champ’s fight to keep the crown from the strange spectacle that is Tommy. Elton’s wizard is both awed and disgusted at how a “freak” could get the better of him. Looking back, it makes sense that most of Elton’s on-screen work post-Tommy has had him often playing a version of himself. (Think John's memorable turn in 2017's Kingsman: The Golden Circle, for example). Only Elton John could give Elton a character as compelling and dynamic as Russell and The Who gave him with the Pinball Wizzard.

The sequence has an extra jolt from The Who all appearing on stage, as they do in scattered moments throughout the movie. Not only Daltrey, but Townshend, Moon, and bassist John Entwistle.

It certainly isn’t a Who movie without seeing the infamous scenes of instrument destruction that made the band iconic.

It says something about how everyone in Tommy delivered that John’s bravura performance as the Pinball Wizard is followed and matched by another infamous highlight, Ann-Margret’s insane, dramatic, sexy, and crazy performance of “Champagne” culminating in her memorable shower of beans and chocolate.

As much as I love the rest of Tommy, it is only in the film’s final 15 minutes that it can return to the operatic heights of “Champagne.” Speaking of which, it could be argued that Ann-Margret seemed to lean more on the “opera” element of “rock opera” when it comes to her vocal performance in Tommy, which she does as if she is doing a production of La Boheme. It is certainly not bad, but just different from the rock and roll atmosphere of The Who. She certainly acquits herself better than Oliver Reed, who is OK and funny but slightly one-note in his singing and performance. Reed’s Frank is missing a mustache to twirl as his character becomes more opportunistic when fortunes change for the better with Tommy. Reed does have one effective moment when Frank looks at Moon’s creepy uncle with stone-faced contempt after Ernie’s chilling act.

As far as Reed’s singing goes, I’ll only say that it’s a thing that happens.

(Where is your charge of “heinous rendition” towards Reed’s singing, Jack Black?)

After Cabaret, movie musicals could never return to the days of Singin’ In The Rain, The Music Man, and another Ann-Marget-related musical, Bye Bye Birdie. Tommy was a musical truly made and designed for the post-Vietnam landscape. Even without the blink-and-you-miss-it cameo by a certain Beatle, Tommy is a musical for the 1970s. Within the music is a story that transcends its time, a satire and critique that touches on dark themes that are still relevant today, and a declaration of independence for anybody who yearns to break free from their shell.

Of course, as in life, the real challenge is after the storm. Daltrey’s Tommy becomes his own person only to get swept up in another form of isolation, as he leans too much into his legend, a persona made before he even knew it. When Tommy, Nora, and Frank, are forced to face the irreversible consequences of that legend, it becomes tragic and humbling, but with enough cracks of light to provide hope for not becoming the answer, as Tommy had mistakenly assumed was his destiny. Rather, hope for anyone comes down to recognizing something bigger guiding us.

(What that "something bigger" is to any of us is, in the end, like City Slickers' "one thing." In other words, it's something one has to find for oneself.)

Tommy does all that while finding time to have Elton John rocking in insanely large boots over a high-level pinball machine. Somewhere, there is also Tina Turner laughing manically, drug-addled yet in full control of her power. Most of all, Ann-Margret is hitting a literally “messy” aria of pain, delusions, and raw emotion.

It just can’t get more insane and crazier than all of that…unless you find time to see the next Roger Daltrey/Ken Russell collaboration, 1975’s Lisztomania, but that’s truly another story.

Sincerely: Random Access Moods

About the Creator

Michael Kantu

I have written mostly pop culture pieces for Medium, Substack, and on a short-lived Blogspot site (Michael3282). I see writing as a way for people to keep their thoughts, memories, and beliefs alive long after we depart from the world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.