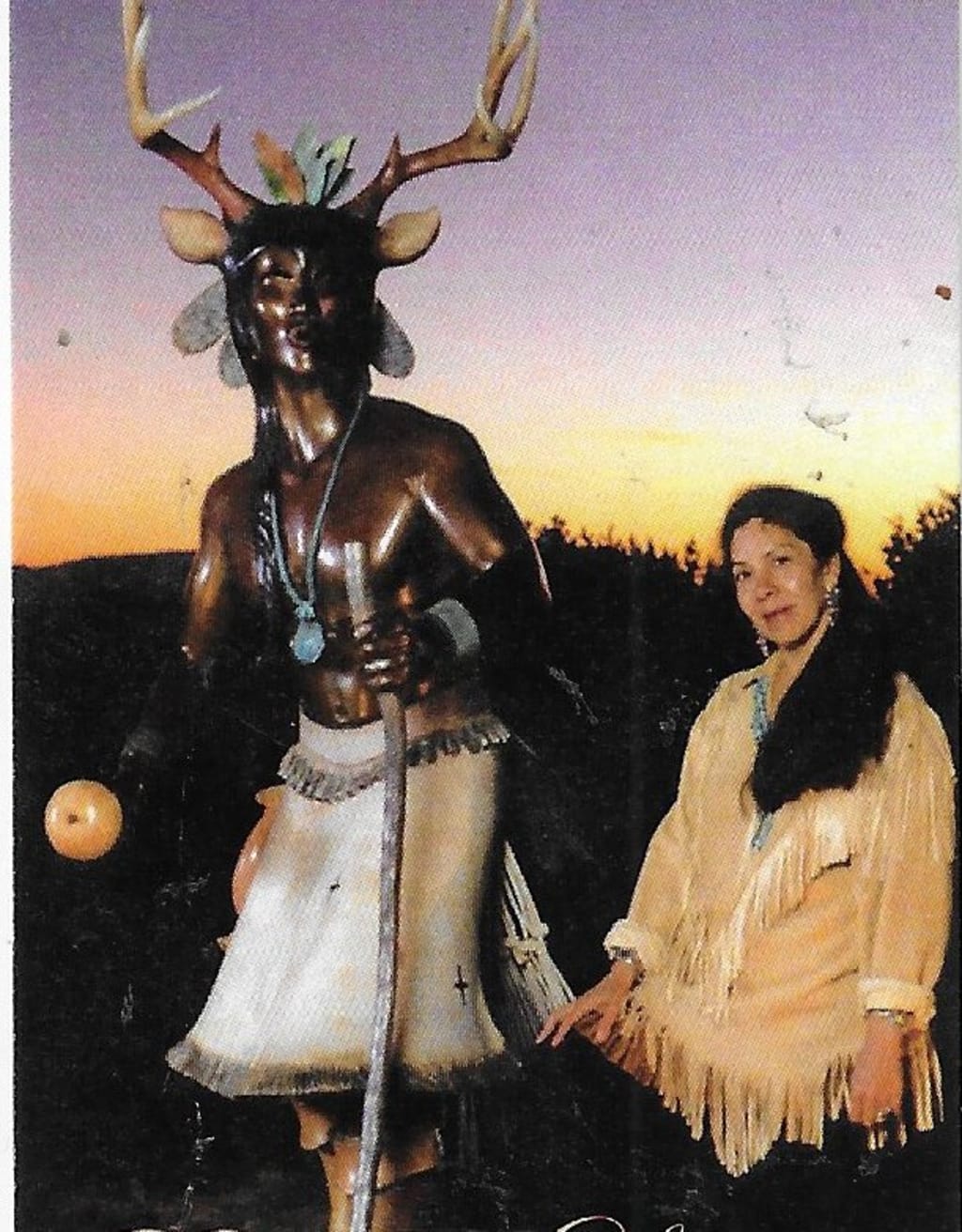

Estella Loretto:

Sculpting Spirit, Heritage, and Time

By Brian D’Ambrosio,

Estella Loretto has lived her 72 years with a sculptor’s patience, chiseling each moment slowly, shaping a life balanced between Pueblo ancestry and monumental artistic vision. Each breath, she says, is a grain of stone, a measure of time, and a spark of spirit.

“I’m more selective now about who and what I spend my time on,” she said, reflecting on a philosophy grounded in gratitude. “We are told when we are born that we are only given so many breaths.”

For Loretto, each breath is sacred — a rhythm that guides her hands, a pulse of Pueblo inheritance, and the discipline of a woman who has carried tradition into bronze.

Ancestry and Early Lessons

Both of Loretto’s parents were from Jemez Pueblo. Towa, the Pueblo language, was the only tongue spoken, she recalled. This immersion gave her not just fluency in words but also an intimacy with a worldview shaped by rhythm, ritual, and reverence.

Her home was alive with creation – “a lot of space and a lot of work happening everywhere,” she said. “I’d wake up in the morning and both my parents were creating. The fire was going. They were having coffee. Dad was doing ceremonial art and Mom was sculpting. I thought every family woke up like that.”

Her mother was a respected potter, shaping clay as both livelihood and spiritual expression. Loretto absorbed the rhythm and began playing with clay, learning early that art was survival, devotion, and service.

Her father, though quadriplegic, never stopped creating. “His hands were always busy. Everybody came to him for ceremonial items, for dancers and sound,” Loretta said.

Though rooted in Jemez, Loretto’s vision reached beyond. She studied at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, then traveled on scholarships to Belgium, Mexico, Japan, India, and Nepal. Each journey expanded her understanding of how art connects to spirit.

In Japan, she apprenticed in traditional pottery and exhibited in Osaka. In India and Nepal, she absorbed devotional practices tied to sculpture and ritual. These global encounters, layered onto her Pueblo upbringing, gave her a unique artistic vocabulary — a symphony of ancestral memory and universal form.

Returning to New Mexico, she apprenticed with Allan Houser (1914–1994). Houser, among the most influential Native American sculptors, encouraged her to embrace monumentality.

“Houser said to start monuments, anything over five feet,” she recalled. His challenge became a turning point that shaped both her art and her ambition.

The Monumental Path

Loretto began sculpting large-scale bronzes, works demanding patience, stamina, and intimacy. Her largest piece to date, a 12-foot statue inspired by her late husband, took three years.

“Little by little, I’d climb up there, open his eyes, do his lips. To do an ear, any little thing, takes so much time. … They are my babies talking to me. You want your baby to be beautiful.

“They are going to be alive forever once I cast them. They are going to be here longer than I am.”

For more than a decade, she ran her own gallery on Santa Fe’s Canyon Road. The space became more than a showroom. It was a gathering place, where on weekends her relatives would show up with drums and start drumming.

After 12 years, she closed the gallery, bought land, and built her home in Santa Fe, where she has been for 35 years. That home remains both sanctuary and studio, where monumental forms emerge in solitude and prayer.

Loretto’s sculptures now stand in sacred and civic spaces across New Mexico – in the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi in Santa Fe, in the State Capitol, and at the Institute of American Indian Arts.

Brian D'Ambrosio is the author of New Mexico Eccentrics, available November 2025 wherever books are sold.

About the Creator

Brian D'Ambrosio

Brian D'Ambrosio is a seasoned journalist and poet, writing for numerous publications, including for a trove of music publications. He is intently at work on a number of future books. He may be reached at [email protected]

Comments