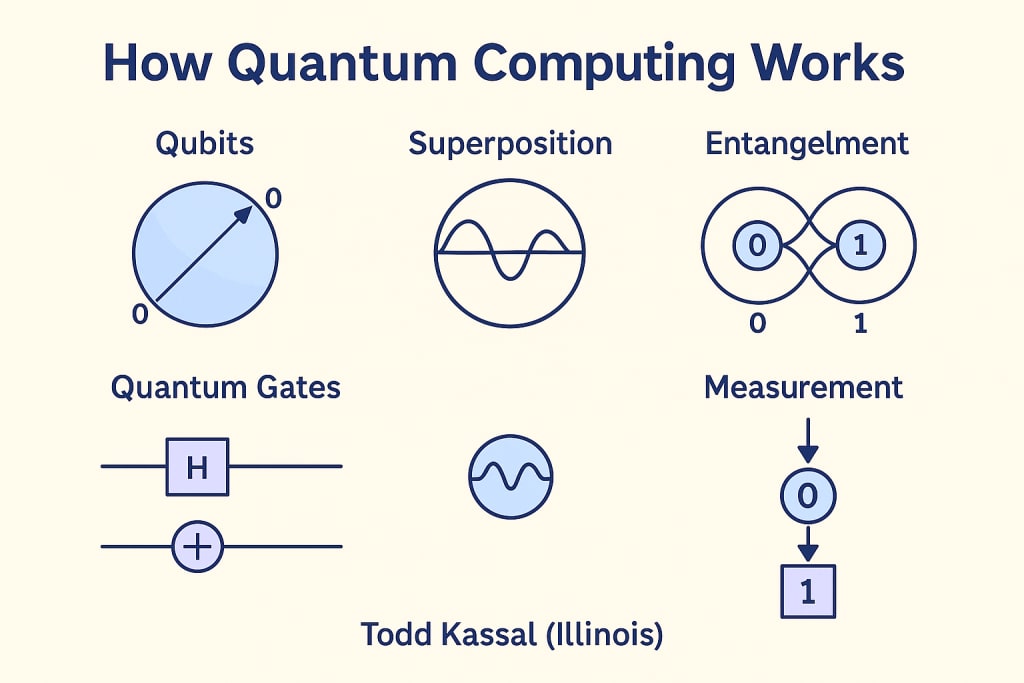

How Quantum Computing Works

A Deep Dive into the Future of Computation

In a world where classical computers have brought about incredible technological advances, a new paradigm is emerging that promises to redefine what is computationally possible: quantum computing. Unlike traditional computers that process information using bits, quantum computers use quantum bits or qubits, unlocking unprecedented processing power for solving certain classes of problems. But how does quantum computing actually work?

Let’s explore the key principles that underpin this revolutionary technology and break down the mechanisms that allow quantum computers to function in ways classical systems cannot.

From Bits to Qubits

In classical computing, information is encoded using bits, which can take a value of either 0 or 1. All computation is ultimately built from combinations of these binary states. A quantum computer, however, uses qubits, which can represent 0, 1, or both simultaneously thanks to a property called superposition.

Imagine a spinning coin. While in the air, it's neither heads nor tails — it's in a probabilistic mixture of both. Similarly, a qubit can exist in a superposition of states, dramatically expanding the amount of information that can be processed in parallel.

But superposition alone doesn't make quantum computing powerful. Enter entanglement.

Quantum Entanglement: The Secret Sauce

Entanglement is a quantum phenomenon where qubits become linked in such a way that the state of one instantly influences the state of another, no matter the distance between them. When two qubits are entangled, the measurement of one determines the state of the other.

This allows quantum computers to perform highly coordinated operations across many qubits simultaneously — something classical computers can’t do efficiently. Entangled qubits can encode and manipulate complex correlations in data, forming the basis for massive parallelism in quantum algorithms.

Quantum Gates and Circuits

In classical computing, logical gates like AND, OR, and NOT manipulate bits. Quantum computing has an analogous system: quantum gates. These gates act on qubits using unitary transformations — operations that preserve the total probability across states.

Some common quantum gates include:

• Hadamard Gate (H): Places a qubit into superposition.

• Pauli Gates (X, Y, Z): Analogous to classical NOT and phase flips.

• CNOT Gate: Entangles two qubits by flipping the target qubit based on the control qubit’s state.

Quantum circuits are built by chaining together sequences of these gates to manipulate qubit states toward solving a problem. However, unlike classical circuits, quantum operations must be reversible, and outcomes are probabilistic — requiring multiple runs and measurements to extract meaningful results.

Measurement and Probability

Measurement is where quantum computing parts ways most significantly from classical systems. When a quantum computer measures a qubit, it "collapses" the superposition into a definite state — either 0 or 1. The outcome is governed by the probability amplitude, a mathematical representation of the likelihood that a qubit will collapse to a certain state.

As a result, quantum computers must often run the same computation multiple times, gathering statistical data to derive answers with high confidence. This is especially true in quantum algorithms, where the solution emerges from the distribution of measurement outcomes.

Quantum Speedups: Why It Matters

The power of quantum computing lies in its ability to solve certain problems exponentially faster than classical computers. For example:

• Shor’s Algorithm: Can factor large integers in polynomial time, potentially breaking current cryptographic systems.

• Grover’s Algorithm: Speeds up unsorted database searches from O(n) to O(√n).

While these algorithms are still mostly theoretical or demonstrated on small scales, they offer a glimpse into the future where tasks that take thousands of years for today’s supercomputers could be done in minutes.

Types of Quantum Computers

There are several physical systems being explored to implement quantum computers:

• Superconducting Qubits: Used by Google and IBM, these circuits operate at near absolute zero temperatures and exploit quantum effects in electrical currents.

• Trapped Ions: Atoms held in place by electromagnetic fields and manipulated with lasers; known for high fidelity and long coherence times.

• Photonic Quantum Computers: Use photons (light particles) to encode and process information.

Each platform has strengths and trade-offs in terms of scalability, stability, and error rates.

Quantum Error Correction

Quantum systems are notoriously fragile. Interactions with the environment cause decoherence, disrupting quantum states and leading to errors. Quantum error correction is a major area of research, aiming to detect and fix errors without directly measuring qubit states.

Techniques like the surface code use additional "ancilla" qubits to redundantly encode logical qubits, enabling robust, fault-tolerant computing. Though error correction adds significant overhead, it’s essential for building practical quantum systems.

Where We Are Today

As of 2025, quantum computing is still in its early stages — what many call the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. Systems with dozens to a few hundred qubits exist, but they are prone to noise and limited in the complexity of tasks they can handle.

Nonetheless, progress is accelerating. Companies like IBM, Google, and startups like Rigetti and IonQ are racing to increase qubit counts and fidelity. Quantum cloud platforms now allow researchers and developers to write and run quantum code, even without direct access to quantum hardware.

The Future: A Quantum Leap

Quantum computing won’t replace classical computers but will complement them in solving specific problems like cryptography, drug discovery, financial modeling, and optimization. The road to a fully scalable, fault-tolerant quantum computer is still long, but the scientific and commercial interest ensures continued rapid development.

If you're curious about where it all began, you can read my companion piece: 👉 The Genesis of Quantum Computing: A Historical Perspective

Author: Todd Kassal (Illinois)

Quantum computing enthusiast and technology writer.

About the Creator

Kassal Todd

Todd Kassal is a seasoned Quantum Computing and Project Management professional with over a decade of experience driving innovation at the intersection of cutting-edge technology and strategic execution.

Comments