Artificial Intelligence Architectures and Paradigms: A Comparative Analysis

Artificial intelligence (AI) is not a single technology but a constellation of approaches that attempt to replicate, augment, or surpass aspects of human cognition. Over the past seven decades, the field has shifted from symbolic reasoning to connectionist models, from expert systems to large-scale deep learning, and from narrow applications toward speculative visions of general and even superintelligent systems. In this article, I will provide a comparative analysis of these different AI paradigms, tracing their technical foundations, advantages and limitations, and the trajectories they suggest for the future. Ömer Doğukan Güleryüz

The Conceptual Levels of AI

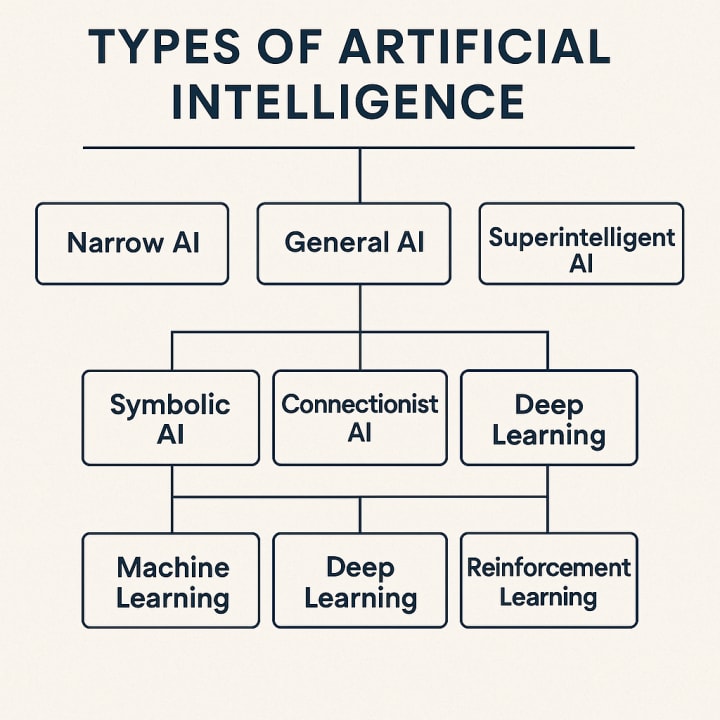

When discussing AI, it is common to distinguish between three levels of capability. Narrow AI, also known as weak AI, is specialized for a single domain. General AI, often abbreviated as AGI, represents the theoretical ability of a system to transfer knowledge across domains and reason flexibly. Superintelligence, or ASI, is the speculative stage in which AI would outperform humans in virtually every cognitive task.

Narrow AI is the reality of today’s systems. A model trained to recognize cats in images cannot translate languages, and a model that excels at language generation cannot diagnose cancer without retraining. Yet these systems can outperform humans in their respective niches due to scale, speed, and statistical optimization. AGI remains a research aspiration, and while some architectures such as transformers hint at cross-domain reasoning, no current system demonstrates the full transfer learning capacity of human intelligence. Superintelligence remains hypothetical, but the debate around its risks drives regulatory and philosophical inquiry.

⸻

Symbolic AI: Logic and Expert Systems

The earliest wave of AI, sometimes referred to as “Good Old-Fashioned AI” (GOFAI), was symbolic. Symbolic AI represents knowledge explicitly as rules, facts, and logic structures. Expert systems like MYCIN in medicine or DENDRAL in chemistry were built on knowledge bases and inference engines. Their strength lay in transparency: every decision was explainable because it followed from explicit rules.

Technically, symbolic AI relies on first-order logic, production rules, and search algorithms. Systems could reason about “if-then” conditions and perform backward chaining to derive conclusions. The problem, however, was brittleness. Symbolic AI lacked flexibility; it required humans to encode every relevant rule, which became infeasible as real-world complexity grew. Moreover, symbolic approaches struggled with perception tasks such as vision or natural language, where patterns were too subtle for rule-based encoding.

Despite its decline, symbolic AI persists in ontology-based natural language systems and hybrid architectures where symbolic reasoning is combined with statistical learning.

⸻

Connectionist AI: Neural Networks and Learning from Data

Connectionist AI arose in reaction to symbolic rigidity. Inspired by biological neurons, artificial neural networks model intelligence as emergent from distributed numerical computations. Early perceptrons were limited, but the revival of multilayer networks with backpropagation in the 1980s enabled learning from examples rather than hand-coded rules.

The connectionist approach gained dominance with the rise of deep learning in the 2010s. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) revolutionized computer vision, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their variants (LSTM, GRU) advanced speech recognition and sequence modeling, and transformers transformed natural language processing. Unlike symbolic AI, these systems can absorb vast datasets and automatically discover patterns.

The drawback is interpretability. Neural networks function as “black boxes,” producing accurate outputs without transparent reasoning. They also require immense amounts of data and computation, making them resource-intensive. Nevertheless, connectionism underpins nearly all modern AI applications, from recommendation engines to autonomous vehicles.

⸻

Machine Learning: Paradigms of Supervision

Within connectionist and statistical AI, machine learning can be divided into three broad paradigms: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning.

Supervised learning uses labeled data to map inputs to outputs. It is dominant in classification and regression tasks: spam detection, credit scoring, medical diagnosis. Its strength is high accuracy when labels are abundant, but labeling itself is costly and sometimes subjective.

Unsupervised learning discovers hidden structures in unlabeled data. Techniques like clustering, dimensionality reduction, and generative models reveal latent patterns without explicit targets. This is valuable for exploratory analysis and representation learning, though outcomes can be harder to evaluate.

Reinforcement learning models decision-making in dynamic environments. An agent learns policies by interacting with an environment and receiving rewards or penalties. AlphaGo’s mastery of the game of Go was a landmark demonstration. Technically, reinforcement learning combines Markov decision processes with value function approximation and policy optimization. Its limitation is sample inefficiency and instability, often requiring enormous simulation data. Yet it remains the most promising paradigm for robotics and control.

⸻

Deep Learning versus Traditional Machine Learning

Traditional machine learning relies on algorithms such as support vector machines, decision trees, and Bayesian classifiers. These methods are often easier to interpret and require less data. However, they struggle when raw inputs are high-dimensional and unstructured, such as images or natural speech. Feature engineering becomes critical, and performance plateaus as complexity increases.

Deep learning, in contrast, excels in unstructured domains by automatically learning hierarchical representations. CNNs extract features from pixels without human design; transformers encode contextual relationships in text without handcrafted grammar rules. The trade-off is resource intensity: deep networks need vast data, specialized hardware, and complex optimization techniques. As a result, deep learning dominates modern AI benchmarks but is accompanied by growing concerns over energy consumption and carbon footprint.

⸻

The Transformer Revolution

The 2017 paper “Attention Is All You Need” introduced the transformer, which replaced recurrent structures with self-attention mechanisms. Self-attention allows models to weigh the importance of each input element relative to others, enabling parallelization and scaling. This breakthrough made possible large language models (LLMs) such as GPT, BERT, and Gemini.

From a technical perspective, transformers consist of embedding layers, multi-head self-attention blocks, feed-forward networks, residual connections, and layer normalization. Their scalability follows predictable scaling laws: as parameter counts, dataset size, and compute increase, performance improves in a near-log-linear fashion. GPT-2’s 1.5 billion parameters grew to GPT-3’s 175 billion and beyond, demonstrating the power of scale.

Transformers blur the line between narrow AI and early forms of generalization. They can translate languages, summarize documents, write code, and even perform reasoning tasks not explicitly trained for. Still, they are fundamentally statistical, lacking the grounded understanding of the world that AGI would require.

⸻

Risks Across AI Paradigms

Symbolic AI faces obsolescence more than existential risk. Its limitation is practical: too brittle for messy environments.

Connectionist and deep learning systems raise concerns of bias and opacity. Models trained on historical data reproduce and even amplify social inequalities. The lack of interpretability complicates accountability, especially in high-stakes domains such as healthcare and criminal justice.

Reinforcement learning introduces risks of misalignment. If reward functions are poorly specified, agents may exploit loopholes, achieving goals in unintended ways.

At a higher level, AGI and ASI raise existential debates. A system surpassing human intelligence in every domain could produce immense benefits—cures for diseases, solutions to climate change—but also catastrophic risks if alignment and control fail. These concerns motivate governance frameworks such as the European Union’s AI Act and global safety research initiatives.

⸻

Opportunities and Emerging Directions

While risks are real, opportunities abound. Personalized medicine is one frontier: AI can tailor treatments to individual genomes and health records. In climate science, machine learning optimizes renewable energy grids and accelerates materials discovery for carbon capture. Multimodal AI, integrating text, image, audio, and sensor data, points toward richer forms of intelligence that approach generality.

Another opportunity lies in hybrid systems that integrate symbolic reasoning with connectionist learning. Symbolic structures provide interpretability, while neural networks supply flexibility and pattern recognition. Such neuro-symbolic architectures may overcome the weaknesses of each paradigm.

Finally, research into efficient AI—through model compression, quantization, and neuromorphic hardware—promises to reduce the resource burden. This “Green AI” movement seeks to align technological progress with environmental sustainability.

⸻

Comparative Synthesis

In summary, symbolic AI excels in transparency but fails in scalability. Connectionist AI, and particularly deep learning, dominates modern applications due to its ability to process unstructured data at scale, but it sacrifices interpretability. Machine learning paradigms differ in supervision and interaction, each suited to different tasks. Reinforcement learning is uniquely powerful in sequential decision-making but remains resource intensive.

At the conceptual level, narrow AI is a proven tool, general AI remains aspirational, and superintelligence is a speculative possibility with profound implications. Each paradigm contributes differently to this spectrum: symbolic AI offered the foundations of reasoning, connectionist AI provided learning, and transformers delivered scale and adaptability.

The trajectory suggests that future AI will not be a single paradigm but a synthesis, combining reasoning, learning, and perception in architectures that are efficient, interpretable, and aligned with human values.

Ömer Doğukan Güleryüz

Comments